Expanding Peer Support Initiatives & Encouraging Peer-To-Peer Mentoring

Erkan Demirbas, Ryan Chapman and Rachel Justice

Lincoln International Business School

Published September 2024

1. Introduction of PSG

The Peer Support Group is a student-led, student-focused initiative overseen by a lecturer/module lead to provide a supportive environment for students to reach out for help with module content. Currently the Peer Support Group offers support in two maths-heavy modules: Business Environment (Micro) and Data Analytics. Although the Peer Support Group is available to anyone, we have found that students who haven’t completed level 3 qualifications in subjects such as mathematics and economics, students with Personalised Academic Study Support Plans, and late arrivals find it particularly beneficial as additional support isn’t always available to them.

For each module we offer in-person group sessions, online group sessions, and 1-to-1 in person or online sessions, during which the volunteer students work through trial questions. The volunteer students undergo training from the University MASH team (Math and Statistic Help) as well as training sessions from the Module Lead (Erkan) to ensure that a high quality of support can be provided.

2. Literature Review

Although there is not a standard structure for Peer Support Groups, with some universities offering mandatory courses (Holt and Fifer, 2018) whilst others view the program as a voluntary part of higher education, the objective of supporting students remain the same across all the programmes. Students are enthusiastic about helping one another, especially in terms of university-level where some skills have been lost in previous education. Mentors are chosen based on a range of criteria such as academic and personal qualifications (Holt and Fifer, 2018), students who have recently undertaken the same course who can understand the challenges of the course (Meer et al., 2017) and a profiling system matching mentor to mentees (Cornelius et al., 2016). However, our Peer Support Group accepts any volunteer students who are willing to offer up their time to attend the training and support sessions.

Likewise, our volunteer students only offer academic support whereas in different programmes mentors also have multiple responsibilities ranging from academic subject knowledge, psychological support, role model and career advice (Holt and Fifer, 2018; Andrews and Clark, 2011). According to Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory this helps to reduce stress and anxiety (Kachaturoff et al, 2020) especially in first-year undergraduate students who have less experience of working independently (Heirdsfield et al., 2008).

The success of the programmes also depends upon the quality of training offered to mentors and the institutional communication they receive (Andrews and Clark, 2011). Successful programmes had academic tutors working alongside mentors (Cornelius et al., 2016; McIntosh, 2017) as well as regular meetings with course administrators (Holt and Fifer, 2018) and monitoring visits (Meer et al., 2017). Mentors also received online or in person training ranging from a few hours to 4 days to prepare them for their role and ensure a high quality of support for students (Cornelius et al., 2016; McIntosh, 2017). Our Support Group follows this structure as volunteer students have multiple training sessions with the University Maths and Help Support Team and the Module Leader throughout the academic year to build upon content knowledge needed to support other students.

Student mentors are motivated by both self and other factors, such as career-related experience (Caldarella et al., 2010) and the sense of positively impacting another student’s life (Kantola and Penttila, 2023). They are also more likely to engage in these programmes if it has a positive effect on their results and resources are available to them (Kennecke et al., 2017). However motivating factors differ between paid and volunteer student mentors as paid mentors focus on helping young people whilst volunteers are focused more on the fulfilment of social needs (Lennox and Leonard, 2010).

Overall, our Peer Support Group encompasses a lot of the mentality of other projects, working with professionals to provide the best support we can. However, we differ in the variety of help available:

- one-to-one sessions: for example, helping a student who missed the first semester due to individual reasons and was unable to receive adequate support from personal connections;

- small groups, where students felt comfortable asking questions and breaking down solutions into manageable and understandable problems; and

- larger sessions where content could be covered in a more informal setting and in a way which may be clearer to some than that conveyed in lectures.

Unlike some of the services mentioned, we also didn’t conduct our work as part of timetabled sessions, instead collaborating in sessions that could accommodate as many students as possible, a step beyond what many academics could commit to.

3. Running the Peer Support Group

We emphasized that participating in this project would have a significant impact on the volunteers' employability skills, including teaching and leadership.

Much of our support was conducted in small seminar-style groups led by one or two support students. Each session shared useful content and answered questions about assessments and about content covered in the previous few lectures. The small sessions allowed for collaboration and sharing of ideas, helping to enhance the community feel of the project and ensure that everyone felt comfortable asking questions and seeking guidance. One of the main factors that made these sessions successful was the support given by professional mentors, including tips on dealing with certain scenarios and providing beneficial help without condescension.

For those who could not attend, we have held online sessions similar to those used in many schools and other environments during the COVID pandemic; and one-to-one sessions to help students in catching up. As such, we believe we reached a large number of students and had a positive impact on the confidence of those studying in the business school.

4. Encouraging Our Students to join the Peer Study Group

As a module leader, I (Erkan) shared with my students how my peers helped me successfully prepare for the final exams, emphasizing that I wouldn't have earned my degree without their support. Since the 2021-22 academic year, I have encouraged those excelling in Economics and Maths to offer help to classmates who may need it in my module. This approach proved highly effective, as it significantly strengthened the One Community spirit among the volunteer students.

Furthermore, after receiving feedback at the Student Experience Panel in 2023, I encouraged my students to join the PSG by promoting the Lincoln Awards, which is a program designed to enhance student employability skills at the university. This approach inspired many students to join the team. Additionally, volunteers are awarded a £10 gift card, sponsored by the Head of the Department. They are also provided with a letter of appreciation signed by the HoD, Module Leader, and Director of MASH.

Finally, as a project team, we emphasized that participating in this project would have a significant impact on the volunteers' employability skills, including teaching and leadership. Our efforts proved very effective, resulting in twenty-six volunteer students over three years.

5. Why Mentors Joined This Project

Our mentors span from first-year undergraduates to PhD students, representing a wide range of backgrounds, including diverse nationalities, genders, and academic disciplines.

Table 1: The level of volunteer students

| Level | Number of volunteers |

|---|---|

| Y1 | 4 |

| Y3 | 2 |

| MSc | 2 |

| PhD | 2 |

| Total | 10 |

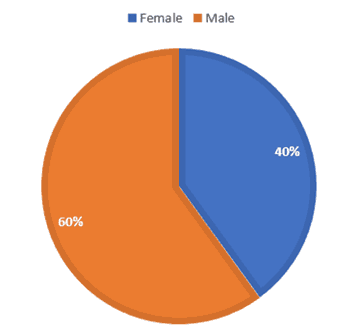

Figure 1: Gender breakdown of volunteer students

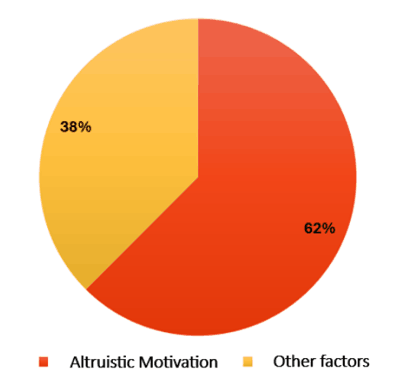

According to our findings, volunteer students in our project are primarily motivated by selfless community and altruistic purposes, such as pedagogical altruism, philanthropic teaching, cultural immersion, reflective mentorship, peer support, mutual learning, and inclusivity.

Figure 2: Motivational Factors for Joining the PSG

One volunteer MSc student expressed this sentiment, stating, “I have never seen a group so committed to helping people without the expectation of getting anything in return as I witnessed in the project.”

Personal and professional development opportunities, including gaining teaching experience, professional growth, and skill enhancement, have also motivated students to join the project. A volunteer PhD student remarked, “Joining this project improved my employability skills”.

Another MSc student highlighted the development of leadership and mentoring abilities, saying, “It helped to develop leadership and mentoring abilities, as guided students through those sessions.”

6. Conclusion

On the whole, we believe the statistics paint our project in a very positive light, when it comes to numerical attainment and overall satisfaction. However, this goes further than just an additional mark on a singular assessment – we believe we are building a stronger framework for these students to build on when learning additional skills and introducing many concepts which may become crucial to future careers. As many of the students on our course have visions of working in large corporations or potentially becoming entrepreneurs themselves, we hope to set our university apart by giving the best support possible in helping along the way.

7. References

J, Andrews. and R, Clark. (2011) Peer Mentoring Works! How Peer Mentoring Enhances Student Success in Higher Education. https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/17968/ [accessed 24 May 2024].

P, Caldarella., R, Gomm., R, Shatzer. and G, Wall. (2010) School-Based Mentoring: A Study of Volunteer Motivations and Benefits. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 2(2) 199-216. ERIC - EJ1052013 [accessed 14 August 2024].

V, Cornelius, L, Wood., and J, Lai. (2016) Implementation and evaluation of a formal academic-peer-mentoring programme in higher education. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17(3) 193-205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787416654796 [accessed 24 May 2024].

A, Heirdsfield., S, Walker., K, Walsh. and L, Wilss. (2008) Peer mentoring for first-year teacher education students: the mentor’s experience. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 16(2) 109-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260801916135 [accessed 24 May 2024].

L, Holt. and J, Fifer. (2018) Peer Mentoring Characteristics That Predict Supportive Relationships With First-Year Students: Implications for Peer Mentor Programming and First-Year Student Retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 20(1) 67-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025116650685 [accessed 24 May 2024].

M, Kachaturoff., M, Caboral-Stevens., M, Gee. and V, Lan. (2020) Effects of peer-mentoring on stress and anxiety levels of undergraduate nursing students: An integrative review. Journal of Professional Nursing, 36(4) 223-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611261003678879 [accessed 24 May 2024].

J, Kantola. and S, Penttila. (2023) What Drives Mentors? The role of benevolence in mentoring motives. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2229371

S, Kennecke., A, Hauser. and S, Weisweiler. (2017) Who Wants to Be a Mentor and Why? Factors and Motives That Drive Students’ Decision to Engage. Academy of Management. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2016.73 [accessed 14 August 2024].

Lennox, J. and Leonard, D. (2010) Motivation of paid peer mentors and unpaid peer helpers in higher education. International Journal of Evidence based coaching and mentoring , 8(1) 85-103. https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/8c6a37ad-0979-4c02-95f5-80f8071f62e6/1/ [accessed 14 August 2024].

E, McIntosh. (2017) Working in partnership: The role of Peer Assisted Study Sessions in engaging the Citizen Scholar. Active Learning in Higher Education, 20(3) 233-248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417735608 [accessed 24 May 2024].

J, Meer., R, Wass., S, Scott., and J, Kokaua. (2017) Entry Characteristics and Participation in a Peer Learning Program as Predictors of First-Year Students’ Achievement, Retention, and Degree Completion. AERA Open, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858417731572 [accessed 24 May 2024].

↑ Top