Andrew Mearman, University of Leeds

Edited by Caroline Elliott, University of Warwick

Published September 2024

This chapter and its connected resources are the product of a collaboration between colleagues at several universities, including those who have contributed case study material. The resources are designed to help directors of teaching, programme leaders, module leaders and individual tutors in aiding students in the various transitions they make through university.

Every student’s journey will be different, and have a different starting point.

Fundamentals

Transition is a broad term, which can be understood as including the more familiar ideas of welcome and induction; but it can (Gale and Parker, 2014) imply a specific approach to those phases, one which recognises that transitions:

- Are long processes

- Are non-linear and messy

- Will differ for different students

- May not fit our pre-conceived notions of how a student experiences university

It is important to recognise from the literature that:

- For students, transitions are dominated by social concerns about integration (Tinto, 1975, et passim) and meaningful social interactions (Astin, 1999), in the pursuit of a sense of belonging and mattering – students are trying to fit in.

- All students struggle with new customs, practices and language, negotiating the hidden curriculum of higher education and economics.

- Whilst students have heard of independent learning, they probably do not understand its meaning, especially in practice.

- Students do not know what they need to know until they need to know it.

- Expectations of university may be quite different from their lived experience, which may lead to initial uncertainty and potentially disappointment.

- Students come from a wide variety of backgrounds often with invisible differences, affecting their capacity to cope with the challenges of the next phase of university.

Practically this means academics:

- Need to be welcoming all year round. Whilst the spectre of Freshers’ Week lingers, many now accept that we need to see an end to Freshers’ Week, to be replaced with a year-round welcome. Welcome does not last a week: think about being welcoming rather than organising a welcome

- Must be realistic about students’ abilities to take in information early on

- Recognise that students sometimes arrive late to university and miss some of the essential information given

- Need to consider the timing of key messages

- Need to get to know students

- Recognise that welcome buddies and other means of peer support are very important

- Should prioritise collaborative cohort-wide exercises that allow students to build community and networks

- Recognise that students place value on meaningful relationships with teachers

The resource is organized chronologically, considering key issues that arise at each stage.

| Pre-university | Welcome | First year | Second year | Final year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students will be | Forming expectations | Establishing foundations, figuring out how university works | Re-evaluating hopes, fears, expectations; learning rules; experimenting developing skills. Starting to plan for the future. | Grappling with difficult material, looking to post-graduation, thinking about placements | Experiencing a higher workload, applying for post-university jobs/study, working on dissertations |

| Students may feel | Concerned about fitting in, academically and, even more so, socially | Nervous and excited about experiencing various types of culture shock, meeting people. Overwhelmed at their new surroundings. | They may be really enjoying their time but also paralysed by choice, may not feel they belong, homesick, struggling to adapt | May experience sophomore slump, especially with year 2 core modules, anxious or excited about opportunities for a year out | Confident and well adapted to university. Overwhelmed by combined workload and stressed about completing it, especially the dissertation. If they are coming back from a year out, may experience reverse culture shock |

| Students may need | Easy access to basic information | A warm welcome, help with foundational things such as locations, accommodation, food | Know how to get support if needed. Help with the hidden curriculum, and to develop academic skills | Advice on year 3 options | Support on managing workload, good dissertation supervision |

This of course presents a stylized simplification of the student’s experience. Every student’s journey will be different, and have a different starting point, even if some students in some groups will likely encounter common challenges, such as grappling with the hidden curriculum. Individual students will also be starting from different points, meaning they experience more or less of the above, plus other issues entirely, or not. In a student's path from A to B, they might move from A to C, go back to A, jump from B to D, or back again, etc. Of course, as well, some journeys end in failure or exit.

Throughout, the chapter’s focus is on key messages, supported by useful internal (generated within the Economics Network community) and external (developed by other relevant bodies) resources. One way to think collectively about these resources is like a tree: the chronological narrative is the trunk, and the various specific resources are its roots and branches.

A key point to re-stress here is that transition is not completed early in a student’s career, but is a continuous process. Several resources are designed to reflect that approach. One good example is the ECOBridge resource designed by Duncan Watson and Peter Dawson at UEA. ECOBridge considers the student journey from INduction to OUTduction, i.e. to students’ chosen careers. As the resource says, its goal is to enhance students’ employability, guided by the skills employers say they want graduates to have – many of which are ‘soft’. ECOBridge directs students to online resources (such as LinkedIn Learning) which interactively foster development of skills and knowledge necessary to excel in Economics and to succeed after graduation.

Another example of a set of welcome resources designed to capture the student’s journey is discussed in Atisha Ghosh’s case study on the University of Warwick’s Moodle VLE. In it, Atisha offers an overview of the VLE, which incorporates essential concepts and tools, as well as some consideration of relevant data, in microeconomics and macroeconomics. As Atisha reports, students reacted positively, not least the students who did not take A-level Economics. Additionally, the student cocreators felt that co-developing the resource had facilitated their development of several skills.

The Warwick Moodle can be understood in the context of the university and department. The latter is discussed in Lory Barile’s case study, which considers other aspects of Warwick’s approach to welcome. The case discusses several initiatives, including building a course Learning to Learn in Economics, which incorporates both the Moodle and the maths refresher materials discussed in Caroline Elliott and colleagues’ case study (see below).

The chapter now follows, largely chronologically, the student journey, beginning with pre-induction activities.

Pre-university activities

Pre-university experiences are crucial because:-

- Students develop study habits that may or may not be helpful to their studying at university – for instance they are often trained intensively to succeed at school / college, which does not support their being independent learners at university.

- These prior experiences feed into expectations of what university is going to be like.

- Educational backgrounds within any cohort can be very different – for example, in the UK much university teaching assumes students have come through the traditional UK A level route, when in fact first year undergraduates may have studied for UK vocational qualifications, an International Baccalaureate, or other (non-UK) national educational qualifications.

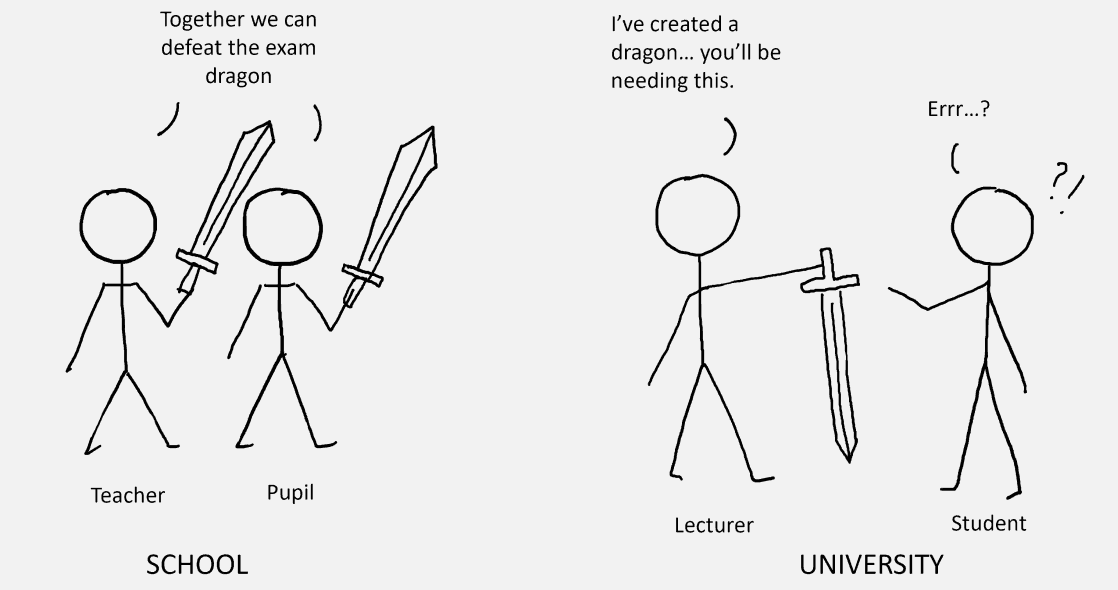

Cartoon by Annika Johnson illustrating the difference between assessment at school and university.

Academics need to understand these experiences if we are going to meet the students coming in the other direction rather than expecting all the adaptation to be done by them. One key thing to remember, as outlined above, is that students are not necessarily focusing on their academic studies when they first arrive at university.

Beyond that, students face various generic challenges of mismatch of students’ background academic skills mismatch and learning practices and what is expected of them at university. More generally, around academic skills and learning practices:-

- Some students have come through different routes: we cannot assume ‘they’ve done this at A level’, which can also be a rather alienating phrase for those who’ve not done A level.

- High-level entrants may have learned some good study habits.

- The same students may have been heavily coached both at school and privately.

- Students are used to working closely to mark schemes.

- Students are supported very well in better academic performance, leading to better chances of getting into their target university.

- Preparation for university study and life offered by schools and colleges may well be fairly limited.

- Students get advice from a wide range of sources, including popular imagery in the media, films, etc. – some are more reliable than others and some are trusted more than others (eg. peers) (see Mearman and Payne, 2023).

- Depending on the university, there might be a lot of support in place to coach students through this initial transition period.

- Some students have learned some degree of independence through research projects; some will have done gap years, but often they still do not understand the nature of independent study.

Another general issue to consider is the so-called hidden curriculum.

The hidden curriculum

Academic English is nobody’s first language (see Huang, 2013) and, whilst previously we may have expected students (or been expected ourselves) just to pick it up, offering students some help in doing so is useful. Assisting students in understanding what is meant by key terms like lectures and seminars (and what to do in them) and how to understand the wording of feedback may have a significant positive impact on them, particularly if they have not come through a UK A-level route.

A barrier to all students when entering the university is the hidden curriculum: terminology, social norms and practices, expectations of behaviour, all of which are different from students’ prior experiences and for which they have no reliable reference points. Questions which may seem basic, such as ‘what is a lecture?’, ‘what do I do in lectures and seminars?’, ‘how does university assessment work?’ and, crucially, ‘what on earth does independent study mean?’, are fundamentally important to all new students. The Economics Network Handbook for Economics Lecturers has various resources supporting teachers in creating better learning environments in lectures and small group teaching: key to these is understanding the student’s perspective.

Students from under-represented groups, including international students, may experience an educational culture shock, and the hidden curriculum creates extra barriers to feeling they belong. This shock will be additional to any they feel as recipients of hidden biases, including things such as reactions to their accent (Ingram, 2009) or other aspects of speech. Margarida Dolan and Dimitra Petropoulou have previously discussed supporting international students in this Handbook chapter.

You can help your tutees by helping them understand the hidden curriculum. To help you, psychologists at the University of Leeds have created the QAA Guide to the Hidden Curriculum. To access this fully you need to a member of Advance HE.

Beyond these generic issues, much of the material in this chapter concerning year one (but also entry into postgraduate programmes) addresses some of the challenges students face learning (or re-learning) Economics content and its associated norms and practices.

Annika Johnson and Alex Squires’ case study discusses some of these issues specific to A levels, and to A-level economics. Their key message is that understanding the differences can help academics in supporting students to make a smooth transition, particularly in the ways in which A Levels are often taught and assessed. They draw the distinction between A-level, in which preparing the student for assessment is a collaboration between them and their teacher, and degree study, assessment for which the relationship between academic and student is much more detached, even adversarial.

Of these, perhaps the most challenging is the mathematical and statistical content of Economics courses. Peter Dawson’s (University of East Anglia) HEA resource explores the mathematical (pre-university) background of incoming economics students. He found that 81% of Economics students said their programmes contained much more mathematics than expected. Such an expectations gap can (except for those who particularly enjoy maths) lead to de-motivation, disengagement, and exit, since these students may have been attracted to Economics programmes by macroeconomic policy and related political questions, behavioural economics, or an interest in finance. These challenges can be magnified when teaching economics to non-specialists, as discussed here by Caroline Elliott and John Sloman.

As Peter Dawson notes, many students may have not studied mathematics for some time and may lack confidence in it. More revision material in year 1 is recommended, extra support, streaming, bridging modules, maths/stats support centres, and diagnostic testing. Similar issues are discussed in Karen Jackson (Westminster)’s Handbook chapter on teaching maths to students from diverse backgrounds.

Whilst many programmes now require A level mathematics or equivalent, other departments with either different approaches to economics, or with a qualitatively different student intake do not. At the University of Leeds, those without A level mathematics are required to take a specialist catch-up maths and statistics course. At the University of Greenwich, they use differentiated tutorial support tailored to students’ backgrounds.

Caroline Elliott and Warwick colleagues Andrew Brendon-Penn, Emil Kostadinov and Jeremy Smith discuss a refresher maths course offered at Warwick, which has been popular with their students. The course focuses on foundational maths concepts, encompassing precalculus; univariate calculus; multivariate calculus; sequences and series; matrices; probability and statistics. Each section of the course starts with a diagnostic test. This is an excellent example of engaging with students to audit their own skills.

Welcome week

A campus treasure hunt encouraged students to explore the physical campus, getting to know where key learning and social spaces were.

Until fairly recently, induction of new students into university was crammed into Freshers Week, with its twin connotations of fresh meat, and that induction can all be done a week. As such, induction week tended to be focused on one-and-for-all transmission of information and otherwise letting students get on with it. Now, though, it is recognised that the initial week at university, whilst remaining important, is so for establishing a cohort identity, helping students orient themselves, make connections and feel settled. We now recognise too that in this first week, key is to help students meet their basic needs, in terms of academics but perhaps more so with life. For them, their focus will be on cooking, cleaning, shopping, meeting people, getting their physical bearings. Hence, "welcome" has been transformed to be more purposive, less full yet structured and, crucially, viewed as only the start of the process of transition.

Information overload can be a real problem – do not try to tell students too much in week 0; or if they are told something in week 0, we should not expect them to remember/know it from that point.

Essentially what they need are light touch things that help them:-

- Get a sense of belonging – This could be on their course/programme but it may be found in student societies, sports clubs, intellectual interest groups, gaming, political or religious groups, organized around their accommodation, or even a feeling of belonging to a physical space (Ahn and Davis, 2020). As Kane et al. (2014) note, belonging can be a crucial driver of success.

- Get to know a few people – As above, this does not have to be via their course but this is a common locus for belonging and it is something you as the academic can influence, in contrast to the other potential sources of belonging.

- Activities to stimulate belonging should be as inclusive as possible (else they will be self-defeating).

- Learn some basics about their course – This will help create a roadmap and a structure, which will enhance their sense of belonging and commitment to the course. It is useful to regularly invite them to reflect on this roadmap.

- Have something to get inspired or excited about their course – This could be images of graduation, or other nods to it, such as attending an early meeting in cap and gown.

Helpfully, there are myriad resources on belonging, as already discussed. This University of Leeds guide highlights several dimensions to belonging and several paths to it. Establishing belonging can be helped by organising events, via the provision of welcome resources and by providing common extra-curricular activities.

Ice-breaker activities can be useful here. This TopHat blog contains some simple ideas, most of which work on the basis that structured activities designed to create interactions work better than accidental ones, especially for less socially confident students. These activities can be done in-person, enhanced by various technologies, or done online. The objectives of such games are to stimulate conversations, but can also address directly belonging, for instance by setting students the task of finding someone from a different country. Another way of showing the geographical spread of a group is to collect locations and display them on a map. A final suggestion is that students pair up and learn how to say another person’s name. This can help that person feel seen and valued so is useful in itself. Such low impact games are also suitable for neurodiverse students, which hints at a key principle of ice-breakers: make them inclusive.

It is typical for welcome week to focus on foundational skills about life at university, how to use the library, etc. Resources and discussion geared to helping new students find their way around, how to behave in the lecture or seminar, physical locations, timings, academic etiquette can all be useful here, as part of revealing the hidden curriculum. At the University of Greenwich, students are presented with diverse alumni role models in a panel on succeeding in economics at both academic level and post-study.

At the University of Leeds, welcome week has focused on meeting personal tutors, getting to know the campus and building communities via classroom games, whilst at the same time having opportunities to meet personal tutors and others teaching them in the first year. A campus challenge, akin to a treasure hunt, encouraged students to explore the physical campus, get to know where key learning and other social spaces were, and directed them to relevant staff offices. Students collected photographs of where they had been, and at the end of the week could submit a video showing their activities. A key consideration here is to make sure the places students need to go are accessible.

In addition, when students gathered in physical classrooms, they played economics games. This was a way to enthuse them about the subject, get them thinking about it, and familiarise themselves with a university environment but in a low-stakes and collaborative way.

Many potential games and experiments exist, as discussed in the foundational Handbook chapter on experiments by Balkenborg and Kaplan, and a wealth of other Economics Network resources available. These include traditional physical games and a selection of computer-based, the availability of which has expanded considerably over time, spurred on partly by the need to provide classroom instruction during the Covid pandemic. For example, newly developed electronic games based on escape rooms have come in too, as discussed in the case study by Maria Psyllou.

In his case study, Guglielmo Volpe (City University, London) discusses some possible pre-arrival readings, including videos and podcasts, films and non-academic books on economics and economic data. These types of resource can engage students using media with which they are familiar, and act as a useful introduction. As with any resource, using such readings must be informed by some principles, such as whether they are intended as passive, or interactive. In either case, students’ use of such resources needs to be curated, either by any reading list being annotated, or their discussion of readings being facilitated by something akin to a book club.

Throughout year 1

We need to ask coaching questions, prompting students to think actively about themselves. Self-awareness of skills is likely to grow their confidence.

Transition into university life may well take the whole year, with students feeling profoundly disoriented for many months. They might benefit from basic guidance about how to transition into university, such as Department of Education (2021).

In year 1 try to get students to embed foundational economic knowledge but also core academic skills, some of which are based in the subject but transferable, while others are clearly more generic:

- Subject specific skills eg. maths

- Literature, referencing, academic conduct, AI

- Note taking

- Argumentation

- Writing

- Competence in specific technological skills eg. Excel and other Microsoft products

and also generic transferable skills and capacities:

- Time management and prioritisation – this can be a particularly important

- Goal setting and planning

- Communication skills

- Curiosity and growth mindset

Students who are goal-oriented may do better so try to get students to think in terms of preferred futures, be that employment, self-employment or future study. We must not assume they are all future Economics PhDs and support them to be equipped to go off in whatever direction they want. We need to ask coaching questions, exploring what the students’ goals are, prompting them to think actively about themselves: can they tell an ‘I’ story, construct a narrative about themselves that is (true and) persuasive, capturing key achievements and challenges they faced? Thus, we help tutees identify their own strengths and weaknesses relevant to their own desired futures, values, beliefs and their ‘possible selves’. This self-awareness of skills is likely to grow their confidence, leading them to further developmental attitudes and behaviours. All of that enhances their career readiness.

One point at this stage is to clarify who is asking these questions. In principle this could be anyone but in higher education, that role is increasingly being played by personal tutors and by specially-trained, experienced peers.

Throughout year 2

To reiterate a key theme of this chapter: transition has not been completed at some point in year 1, it carries on, as the student continues to make their way through their degree journey. The second year has typically been considered a consolidation year, when the student is settled but under less pressure than in their final year. Hence, students have been said to suffer from a ‘sophomore slump’, during which their engagement and enthusiasm suffers. As Webb and Cotton (2019) discuss, this can be a stressful time. Remember, as well, that year 2, far from being an off-year, is also characterised by:-

- Possibly for the first time, proper independent living, outside of any university accommodation (NB Thompson, et al. 2021)

- Particularly for less well-off students, but more generally considering recent cost-of-living increases, living in year 2 may require working part-time.

- Year 2 often counts towards degree classification, even if usually no more than 50%.

- Year 2 marks can be a signal to potential Masters admissions tutors and to potential employers, so they do matter. Students may feel more pressure than in the first year.

- In many universities, because of their value, study year abroad and placement opportunities are promoted. Applying for these, preparing for and undertaking their (often multi-stage) recruitment processes, can be extremely time consuming and energy sapping.

- The combination of these various extra-curricular activities mean many students are not able to focus on their studies in a way that we, their teachers, might like.

- Additionally, in Economics it is traditional that second year courses have technical modules in micro, macro, stats, maths, and econometrics, which are often quite dry, with the risk of reinforcing disappointment about students’ subject choice (see above).

If we accept that year 2 is not so different from year 1, it follows that much of the material above applies. Tutoring and peer support remain important, as does extra assistance from various services supporting career planning. Recall too that students travel through their academic journeys at different speeds so, whereas one student may have learned to navigate the hidden curriculum quite well, for others this may not be the case. Again, individualised conversations with students are necessary to assess their progress.

Notwithstanding the above, some generic points can be made. First, ‘welcome back’ meetings can help make students feel welcome again, but with less emphasis on settling in. Second, since the content of year 2 will be different, it is worth addressing that. If indeed modules do have their traditional technical focus, this is something that can be addressed. Third, as many students will have the opportunity to do a dissertation in final year, some preparation for that will be necessary, either by having a module that supports this directly (for example by having students write a proposal) or through more indirect support, via the development of pertinent skills. Fourth, where students are encouraged or allowed to take up placements, at a suitable time – i.e. not in week 1 – resources to help inform them ought to be shared. Two useful resources to support potential placement students are RateMyPlacement and Unifrog.

Placements and study abroad

Why do students consider placements? What are the benefits? There is some other evidence on the benefits or not of doing a placement (see Brooks and Youngson, 2016). In their case study, Chris Jones and Agelos Delis from Aston University discuss the placement premium, i.e. the potential earnings and performance gains for students who undertake an industrial placement. They discuss the pros and cons of doing a placement, as well as the issues facing students transitioning in and out of placement. This is an essential resource for those advising students about whether to do a placement or not, as well as helping them through the process.

Also, there is some evidence about the potential benefits of doing a Study Year Abroad (SYA), for instance in terms of what Berg and Hagen (2011) call ‘experiential pluralism’. Any positive effect on academic performance may be lower than for doing a placement (Jones and Wang, 2023) or even negative: – Nwosu (2022) suggests students may do academically worse after a SYA. Anecdotally, some students report feeling de-skilled academically even though they have had a very rich cultural experience, especially when they undertake study years abroad on a pass/fail basis.

It is well known that placement and SYA students need to be supported. Auburn (2007) presents the work-placement journey as a transition model, the student traversing the boundary between their roles as participant in higher education and in the work setting. These shifts constitute profound shifts in identity for the student, which can be liberating and exciting but also generate trepidation.

Relevant resources for supporting placement students include these from ASET, the Bright Network, the UK Department for Education, and Universities UK, who clearly see supporting placement students as a mental health concern.

Peter Dawson’s case study discusses how, at the University of East Anglia, students are supported in and out of industrial placement. In addition to events about seeking and getting placements, students are invited to a ‘step into work’ workshop, partly led by Placement Ambassadors, who encourage students to record their own reflections on their placement. Similarly, students who are often apprehensive about returning to their studies are offered the opportunity to present about the value of their experience at a Placement Conference, which as Peter says, showcases to others the benefits of placements, gives value to the individuals, and builds community between placement students.

Throughout final year

The final year of an undergraduate programme has traditionally been seen as the most challenging academically, combined with the fact that at its conclusion, the student is likely to be – often for the first time – leaving education and their identity as a student. Whilst most students might be expected to have adjusted fully to being a student by this point, it remains true that some have not fully adapted to university study, and/or have not taken self-developmental opportunities. Key matters to note for the final year include:-

- Some students returning from study year abroad or industrial placement may experience a reverse culture shock, perhaps feeling they have forgotten how to be a student. Students on placement in particular may have improved their time management and organisation but may struggle without the constant support of a manager. Both case studies by Chris Jones and Agelos Delis, and Peter Dawson consider support for students transitioning back in to university.

- Even more than in the second year, students are not focused on their studies, because of applying for jobs or postgraduate study, at precisely the time the academic challenge is greatest. Differences may be stark between those students active in the labour market and those who have either secured post-graduation employment or who have opted to take a year out, at least in terms of their anxiety levels.

- As above, some students will need to undertake part-time work to meet living costs.

- Even though it is now much less common than before to base degree classifications purely on final examinations/assessments, students will experience a step up in terms of difficulty, intensity and pressure. Of course, though, typically final year modules are more applied and often students have more choice, so they might be more engaged.

- Students may be expected to undertake a dissertation, which can be rewarding but also quite daunting.

Dissertations

According to data collected in 2008, supporting Peter Smith’s Economics Network Handbook chapter on dissertations, some form of dissertation is compulsory for students in many single honours Economics programmes. Dissertations carry a range of credits, require a range of word lengths, and vary in the freedom of students to choose their topic. Whilst most respondents to Smith’s survey reported a free choice, other models exist, including those in which students are given a range of topic areas, matching the research interests of potential supervisors.

Dissertations are regarded as significant, synoptic, capstone projects that allow students to choose, design, manage and execute a research project, adding some small value to the literature. As Smith’s chapter on dissertations says, the dissertation can be “a rewarding and satisfying experience that gives them the opportunity to undertake an in-depth study of a topic that interests them”.

However, Smith goes on to note that dissertations “can also become a traumatic and disillusioning venture for students who do not engage with the research, or who have a bad experience with some aspect of the dissertation process” (p. 1). The dissertation is the zenith of independent learning, which as discussed above, is a notion and a set of practices they struggle with. Of course, for some students it is both and, like university more generally, can be rollercoaster ride. An undergraduate dissertation is a mini-version of the PhD journey, or even worse, given that an undergraduate did not necessarily sign up to do research and in most cases has no aspirations to do any in their future jobs. They are also typically relatively young and inexperienced, having probably never undertaken research before. They often have no idea how to begin.

A myriad of guides can be found on how to do a dissertation, which are good, but largely generic (Wisker, 2018; Greetham, 2019) or applied to other subjects (for example, Young, 2022 in Criminology). In Economics, Smith’s guide and the Studying Economics resources are useful. Drawing some of the elements of these together, here are some useful pointers:-

- Where the dissertation is scaffolded by previous modules – for instance on general or specific (for example experimental) research methods – these modules ought to inspire topic ideas. Inspiration can come from elsewhere, for instance from a student’s industrial placement or study year abroad. Otherwise, early taught provision in final year – and associated guides – should not be afraid to repeat basic information about what a dissertation is, and what can be done.

- Choosing a topic – this is hard not least because writing a dissertation in Economics offers a vast range of options. The range of topics here is indeed huge and, as Economics changes, moving into more areas, drawing on newer methods and data, this range grows. A suitable topic needs to be in the discipline, match with the student’s skill set, be feasible in terms of time (including for primary data collection) and cost, and in many cases add some value.

- Most dissertations will be empirical, and most of these in Economics will be quantitative using secondary data; however, guidance may be needed here on issues probably not previously faced, such as data management, openness for example requiring statistical log files, submission of raw (if anonymised) survey or qualitative data such as surveys, and the fact that often secondary data sets are not pristine and require cleaning and/or compromises – this may all be new to students.

- Providing examples may help – particularly as students are attuned increasingly to learning via demonstration on YouTube. The University of Leeds has published some of its previous undergraduate dissertations, more or less as they were submitted, to give students ideas about what could be done. However, providing examples contains dangers of emulation, copying, short cuts and potential academic misconduct.

- Avoiding analysis paralysis – or the horse/donkey trap. When frightened, the horse runs away, whereas the donkey stays still. Neither is advisable for dissertation students, who need to try to tackle their issues and keep the dissertation moving forward.

- Here, too, project and time management are crucial – advise students to plan their year and make sure they build in time to keep the dissertation progressing. Even if they have front-loaded their years in terms of module choices and/or job search, students need to ensure project feasibility as soon as possible.

- Expect all students to consider research ethics, whatever their topic. Even when students are conducting dissertations on seemingly uncontroversial topics using secondary data, they ought to be exposed to key ethical issues such as informed consent and that research can be used for purposes contrary to the researcher’s intention.

- Dissertations often contain a self-reflective, self-critical segment – this can be difficult – unfamiliar and troubling as it forces students to admit fallibility and uncertainty - and students need training in how to do this. However, it can be useful in helping the student think critically about their own skills that the dissertation has helped to develop.

Finally, it is very important to be clear about the supervisor role – what it is, and what it is not. Various models abound, partly depending on the nature of the dissertation. Typically, the supervisor is an occasional guide, an advisor, a stimulator of the student’s own ideas and solutions. They are not managers, co-researchers or friends. A good supervisor will take this on board but should not go too far. Supervisors who are aloof, unhelpful or appear uncaring are not doing their jobs, even if they might claim it promotes student independence.

Entering taught postgraduate study

Given that the students are in Masters courses for only a year, the need for support all year round is arguably greater than for undergraduates.

Some academics may still labour under a misapprehension that students entering a Masters programme are necessarily the best undergraduates, already fully adjusted to studying within UK higher education. True, new taught postgraduate students (PGTs) have usually studied in higher education before and therefore have learned some of the essential survival techniques. However, it would be wrong to assume they are ready to go. Yet they are expected to hit the ground running hard – Masters programmes are intense. In fact, many of the issues facing new taught postgraduate students resonate with the experiences and challenges undertaken by new first year undergraduates:-

- Many PGTs enter courses as a fall-back, for labour market competitiveness reasons, or from family expectation, so may not be as motivated.

- Many new PGTs will be new to their institution and will spend a lot of time learning where things are, how long things take, how processes work, what the culture of the institution is like.

- Most obviously those who have not studied in the UK before will spend some time adjusting to culture shock. Local customs, UK higher education norms, UK teaching, learning and assessment methods, and for those coming from countries with other dominant languages, the challenge of learning and applying English in both everyday and academic contexts can be a source of anxiety (Horwitz, 2001).

- Students do not have homogeneous backgrounds and some may therefore spend considerable effort catching up on foundational economic concepts and disciplinary norms. The extent of this challenge will vary according to institutional admissions criteria.

Many of the resources already discussed will be hence applicable to PGTs. Here we list a set of activities already practiced within the Economics Network’s institutions, which in principle would work well for PGTs.

- Caroline Elliott et al.’s refresher maths course applies to PGTs as well, especially those coming into Economics from less quantitatively-oriented disciplines.

- Many of the ice-breaker activities and resources discussed earlier will apply. Given that PGT cohorts are often more heavily populated with students from outside the UK, the need for these welcoming and belonging activities becomes stronger. Again, it exposes members of the cohort to the other people in the programme as potential learning resources (see Deuchar 2022).

- Students coming into the UK may benefit from suitably-timed extra provision and discussion of academic misconduct. Some evidence shows that messaging on plagiarism too hard and too soon can create anxiety in students, particularly if English is not their first language, leading them to commit worse academic misconduct offences than they otherwise would. Bond (2018) then advises international students to “try not to spend time worrying about plagiarism as an abstract idea. Instead spend more of your time reading and writing to help you develop your own understanding”.

- Given that the students are in Masters courses for only a year, the need for support all year round is arguably greater than for undergraduates – and indeed many entrants into PGT expect higher levels of support through, for example, personal tutoring.

- Personal tutoring and peer support therefore have an essential role.

- Since students need to get moving more quickly, students are often invited into pre-sessional courses. Additionally, these are sometimes streamed, according to the pathway the student is on and/or their route in, similar to how first year undergraduate provision may be organised. These courses offer a platform, for when the MSc course proper starts.

- The ECOBridge resource at UEA has embedded in it self-assessment quizzes, helping students to understand their ‘learner type’. As with all such resources, students should only regard quiz results as indicative, and they should consider their responses with someone else, for instance their personal tutor.

- In a similar light, diagnostic testing can be useful. Early in a course, new students can be set short assignments or quizzes to get a baseline assessment of their level of skill or knowledge in maths, stats, or economics, and their confidence in writing. These assessments can be used to help students identify their own needs for skill development, and for signposting to relevant services.

- Dissertations at Masters level can be more challenging than at an undergraduate level, as they are intended to be of a higher quality and tend to be completed in a shorter time window. It is often assumed students have all done one before and are therefore equipped to do so again. In fact, many students have not, and are not, so they struggle mightily. Academics at PGT level need to be extra careful not to bury students under the weight of their assumptions and need to scaffold their students’ dissertations at least as strongly as discussed above.

Personal tutoring

Academic Personal Tutoring as a high value-added activity that plays an important strategic role in supporting student success, a prime catalyst of the student experience, helping the student feel they belong and matter. Academic personal tutors (APTs) empower their tutees to succeed. APTs provide personalised support and guidance to help students navigate the transitions in their diverse, non-linear journeys, recognising their different starting and end-points. APTs provide a connection to the university and support at all undergraduate levels and postgraduate study, including into placement and study abroad opportunities, and transition back into university. It is clearly found in an extensive literature that tutoring is important in terms of retention, progression and outcomes (Yale, 2019, 2020; Grey and Osborne, 2020).

Personal tutoring can mean several things and be done by people in quite different roles. In some institutions, tutoring is distributed across all staff but a growing view is that it can be counterproductive to ask staff to tutor if they do not want to, or view the task as free workload. Thus, models of specialist academic staff, or even professional non-academic staff carrying out the tutoring are increasingly common (Thomas, 2006).

There are competing theories in the literature on the role of the tutor (Grey and Lochtie, 2016; Earwaker, 1992; Thomas, 2012; Drake, 2011), including the counsellor, the coach, the critical friend, or relational navigator (Burke, et al. 2021). Traditionally, in the UK, drawing on the concept of loco parentis, tutoring has been pastoral.

However it is designed, personal tutoring has an overarching developmental approach, applied in three general areas of interest: academic performance, pastoral care and personal/professional growth.

Tutors are not expected to be fully skilled coaches but will need to use coaching skills. Key to that is asking ‘coaching questions’, which in essence is inviting the student to identify their own goals, values, drivers and objectives, and to explore where they are in terms of their own capacities relative to those goals. Do they have a "growth mindset" (Dweck, 2016)? In terms of employability, tutors are helping them explore their own career readiness. According to some student Careers Career Readiness data, having these goals is a good predictor of final degree outcomes.

Similarly, tutors are not expected to be fully qualified counsellors – indeed University Counselling Services are often keen for tutors not to act in that role – but at times they will need to deploy counselling skills. Again, the first step is to ask counselling questions, such as a simple "How are things?", or in a subsequent meeting to ask "how are things with x now?" The next key step is to give the student the chance to respond to the question, and again to listen carefully to their response. If they respond with a quick–but perhaps unconvincing–"fine" your next step might be to ask them again.

Peer-assisted learning schemes

An important thing for personal tutors to remember is that they are part of a much wider web of support for students. Among the other elements are Peer-Assisted Learning (PAL) schemes. PAL schemes vary, including the following methods:-

- Structured study sessions overseen by module leaders

- Less structured study sessions driven by student concerns on specific modules

- Semi structured sessions on more generic academic skills

- Mentoring schemes

- Pastoral support

- Student-led and designed activities more akin to student societies

Of these, the mentoring and pastoral elements are likely to be individual, whereas the other sessions will be run in groups. PAL schemes are typically voluntary but may be timetabled to encourage attendance.

PAL schemes are attractive because they give the PALs development opportunities, they allow universities to provide support that would otherwise be impossible, and because students generally trust their peers. From a university perspective, though, it is a concern that PALs are effectively trained and mentored, since peer messages are not always reliable.

The case study by Chapman and colleagues at the University of Lincoln discusses a peer study group scheme on a first year data analytics class, for which they find some evidence of helping students feel better supported, as well as a good opportunity for the mentors themselves.

UEA has a well-established PAL scheme. Separate PAL schemes are designed differently at UG and PGT, to cater for the different needs of the students. Key to this scheme is the clear set of expectations around the role, and a clear training programme, which identifies the precise duties and time commitment of being a PAL mentor. The scheme is sold to potential mentors via its prospective benefits, including self-development, networking opportunities and deeper familiarisation with university processes. As one mentor responded to the scheme: “It has made me realise how much I have learnt … and I have enjoyed sharing my wealth of knowledge with the first year students”, a confidence boost which could itself be valuable to that student. UWE Bristol is another university with a PAL scheme, with a lot of documentation publicly online.

References

Resources connected to this chapter

Barile, L., 2024. Bridging activities/resources to help transition to university at UG/PGT level. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n4114a

Dawson., P., 2024. Transitioning into and out of Work Placements. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n4117a

Elliott, C., Brendon-Penn, A., Kostadinov, E., and Smith, J., 2024. Supporting Economics Students’ Transition to University with Mathematics Revision Resources. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n3936a

Ghosh, A., 2024. Transition to an Economics degree: Key Resources. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n4113a

Johnson, A., and Squires, A., 2024. Understanding A Levels and A Level Economics: A guide for Economics Lecturers at Universities. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n4124a

Jones, C. and Delis, A., 2024. Work Placements in an Economics Degree. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n3937a

Volpe, G., 2024. Pre-arrival Reading: engagement, identity, belonging. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n4125a

Other cited works

Ahn, M.Y. and Davis, H.H., 2020. Four domains of students’ sense of belonging to university. Studies in Higher Education, 45 (3), pp. 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564902

Astin, A.W., 1999. Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of college student development, 40 (5), p. 518

Auburn, T., 2007. Identity and placement learning: student accounts of the transition back to university following a placement year. Studies in Higher Education, 32 (1), pp. 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070601099515

Balkenborg, D., and Kaplan, T., 2009. Economic Classroom Experiments. In The Handbook for Economics Lecturers. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n835a

Berg, D.M. and Hagen, J.M., 2011. Experiential pluralism: gains from short-term study abroad programmes in the business curriculum. International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education, 2 (4), pp. 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPEE.2011.046026

Bond, B., 2018. The long read: Inclusive teaching and learning for International students. Leeds Institute for Teaching Excellence Blog. University of Leeds.

Brooks, R. and Youngson, P.L., 2016. Undergraduate work placements: an analysis of the effects on career progression. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (9), pp. 1563–1578. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.988702

Burke, P.J., Cameron, C., Fuller, E. and Hollingworth, K., 2021. The relational navigator: a pedagogical reframing of widening educational participation for care-experienced young people. International Journal of Social Pedagogy, 10 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.ijsp.2021.v10.x.015

Chapman, R., Justice, R., and Demirbas, E., 2024. Supporting Students through Peer Study Groups. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n3958a

Dawson., P., 2014. Skills in Mathematics and Statistics in Economics and tackling transition. The Higher Education Academy STEM project series. The Higher Education Academy. https://advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/skills-mathematics-and-statistics-economics-and-tackling-transition

Department of Education, 2021. What students need to know about transitioning into higher education. The Education Hub. https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2021/08/12/what-students-need-to-know-about-transitioning-into-higher-education/

Deuchar, A., 2022. The problem with international students’ ‘experiences’ and the promise of their practices: Reanimating research about international students in higher education. British Educational Research Journal, 48 (3), pp. 504–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3779

Dolan, M., 2012. Supporting International Students of Economics in UK Higher Education. In The Handbook for Economics Lecturers. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n2264a

Drake, J.K., 2011. The role of academic advising in student retention and persistence. About Campus, 16 (3), pp. 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.20062

Dweck, C., 2016. What Having a “Growth Mindset” Actually Means. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/01/what-having-a-growth-mindset-actually-means

Earwaker, J., 1992. Helping and Supporting Students. Rethinking the Issues. Open University Press. ERIC ED415731

Elliott, C., and Sloman., J., 2024. Teaching Economics to Non Economics Majors (updated version). The Economics Network. https://economicsnetwork.ac.uk/themes/nonspecialists

Gale, T. and Parker, S., 2014. Navigating change: a typology of student transition in higher education. Studies in higher education, 39 (5), pp. 734–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.721351

Greetham, B., 2019. How to write your undergraduate dissertation (Vol. 108). Bloomsbury Publishing. OCLC 1084350077

Grey, D. and Lochtie, D., 2016. Comparing Personal Tutoring in the UK and Academic Advising in the US. Academic Advising Today, 39 (3). https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Comparing-Personal-Tutoring-in-the-UK-and-Academic-Advising-in-the-US.aspx

Grey, D. and Osborne, C., 2020. Perceptions and principles of personal tutoring, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44 (3), pp. 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1536258

Horwitz, E., 2001. Language anxiety and achievement. Annual review of applied linguistics, 21, pp.112–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190501000071

Huang, L.S., 2013. Academic English is No One's Mother Tongue: Graduate and Undergraduate Students' Academic English Language-learning Needs from Students' and Instructors' Perspectives. Journal of perspectives in applied academic practice, 1 (2). https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v1i2.67

Ingram, P.D., 2009. Are Accents One of the Last Acceptable Areas for Discrimination? The Journal of Extension, 47(1), Article 8. https://open.clemson.edu/joe/vol47/iss1/8

Jackson, K., 2012. Dealing with students' diverse skills in maths and stats. In The Handbook for Economics Lecturers. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n2250a

Jones, C. and Wang, Y., 2023. The performance effects of international study placements versus work placements. Higher Education, 85 (3), pp. 689–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00861-5

Kane, S., Chalcraft, D. and Volpe, G., 2014. Notions of belonging: First year, first semester higher education students enrolled on business or economics degree programmes. The International Journal of Management Education, 12 (2), pp.193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.04.001

Mearman, A. and Payne, R., 2023. Reflections on welcome and induction: exploring the sources of students’ expectations and anticipations about university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47 (7), pp. 980–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2023.2208054

Nwosu, C., 2022. Does study abroad affect student academic achievement?. British Educational Research Journal, 48 (4), pp. 821–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3796

Psyllou, M., 2023. Escape the classroom: a game to improve learning and student engagement. Ideas Bank. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n3633a

Smith, P., 2016. Undergraduate Dissertations in Economics (revised version), In The Handbook for Economics Lecturers. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n169a

Thomas, L., 2006. Widening participation and the increased need for personal tutoring. In Personal tutoring in higher education (pp. 21–31). Trentham Books. OCLC 64098094

Thomas, L., 2012. Building student engagement and belonging in Higher Education at a time of change. Paul Hamlyn Foundation, 100 (1–99).

Thompson, M., Pawson, C., & Evans, B., 2021. Navigating entry into higher education: the transition to independent learning and living. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45 (10), 1398–1410. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1933400

Tinto, V., 1975. Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of educational research, 45 (1), pp. 89–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170024

Webb, O.J. and Cotton, D.R.E., 2019. Early withdrawal from higher education: a focus on academic experiences. Teaching in Higher Education, 23 (7), pp. 835–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0268-8

Wisker, G., 2018. The undergraduate research handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing. OCLC 1158429869

Yale, A.T., 2019. The personal tutor–student relationship: student expectations and experiences of personal tutoring in higher education, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43 (4), pp. 533–544, https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1377164

Yale, A.T., 2020. Quality matters: an in-depth exploration of the student–personal tutor relationship in higher education from the student perspective, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44 (6), pp. 739–752, https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1596235

Young, S., 2022. How to write your undergraduate dissertation in criminology. Routledge. OCLC 1280274680

↑ Top