Understanding A Levels and A Level Economics: A guide for Economics Lecturers at Universities

Dr Annika Johnson

University of Bristol

and Dr Alex Squires

University of Manchester

Published August 2024

Key Takeaways

- The majority of UK university applicants (particularly England, Wales and Northern Ireland) study 3 A Level qualifications, in various subject combinations, prior to commencing their undergraduate studies.

- The way in which A Levels are often taught and assessed differs from undergraduate studies, which may lead to challenges for students in their transition to university.

- Understanding the differences can help university lecturers in supporting students to make a smooth transition to the teaching and assessment practices expected of university level economics.

Introduction

The nature of teaching and assessment can change considerably between studying for A Levels and a degree in economics, but students are not always aware of these changes. This is unsurprising since many elements of university education can initially appear similar: Lecture halls and seminar rooms may be bigger in scale, but they are largely comparable with the operation and function of school classrooms. High stakes terminal exams sat in expansive exam halls also remain a common feature of economics education at both levels. This means students can carry over beliefs from A Level to degree study about how best to approach their education. However, there are some areas of teaching and assessment practice which are less similar than they appear on the surface and this can make the transition to becoming an effective university student even more challenging.

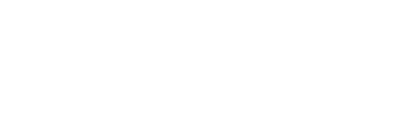

Figure 1: Different approaches at school and university. Johnson (2022).

During A Levels, the student and teacher work together to best prepare the student for unseen exams. These exams are set and graded by a national (or international), external exam board. The teacher does not know the exam questions and does not mark the exam. The style of the exam and the itemised syllabus from which the questions will be drawn are available to all on the exam board website. Students typically receive a lot of individualised feedback on their work and overall progress from the teacher. Students will also be prepared for their exams with a series of mock exams and will have access to an extensive range of past papers, mark schemes and detailed examiners reports providing commentary question by question on selected samples of past work. Any changes to the syllabus are clearly announced in advance and additional preparation materials provided if the change is significant.

This contrasts to degree level study where students are expected to be more independent in their learning and there is greater variation in the assessment methods. Although there are broad guidelines (eg. QAA statements (QAA (2024)) on degree content) lecturers typically create their own detailed syllabus and design all aspects of the assessments, which they also grade. The syllabus can change each year for a number of reasons: to reflect a shift in research practices, attempts to align content with industry practices, or to better fit the different specialisms of a new lecturer. If assessed by exam, then past papers may well be available from the university library, but there is no requirement for exams to be comparable year on year. This means the student can no longer rely on testing their knowledge of a finite syllabus against a large test bank, but instead must focus on mastering the tools and developing deep understanding from the taught components of the course, ready to apply them independently in a less familiar environment. The lecturer will design the assessment with this structure in mind, but if a student doesn’t know how to tackle this challenge, they may understandably feel underprepared without the same test bank tools they have successfully relied on in the past.

In this article we first outline what an A Level is, including the subjects they cover and how they are assessed and graded, before discussing how the experience of studying A Levels can impact a student’s approach to university study. We provide some simple suggestions for lecturers on how they can adapt existing materials or conversations to ease students’ transition to university study.

It is important to keep in mind the prior educational experience of their students and how this may impact their expectations of their undergraduate studies.

What is an A Level?

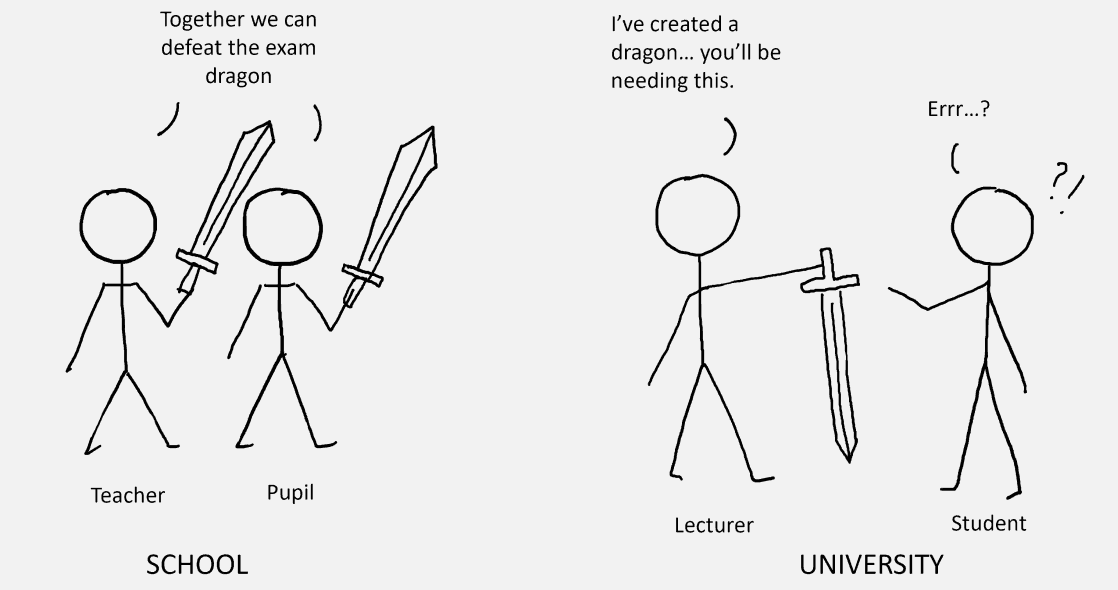

A General Certificate in Education Advanced Level (more commonly known as an A Level) is a qualification completed at the end of secondary education (high school) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Typically, students study three A Level subjects in the final two years of secondary education, between the ages of 16 and 18.

Figure 2: Illustrative structure of secondary education in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. (Johnson et al. (2023))

There are many different types of institution (providers) which offer A Level courses. Most commonly, students will complete their A Levels during their final two years at a school (for 11-18 year olds) or a specialist sixth form college (for 16-19 year olds). Providers teach the A Level, but the assessment is set and exams are marked by one of the national exam boards, who are also responsible for awarding the A Level certificates. The biggest exam boards are AQA, Pearson Edexcel, OCR, WJEC (in Wales) and CCEA (in Northern Ireland).

A levels can also be taught outside of the UK. They are a comparable qualification but may offer different subjects or syllabi which better suit the region in which it is studied. International A levels are provided by exam boards such as Pearson Edexcel and Cambridge International.

Which subjects do A Levels cover?

In the UK there are over 30 different subjects available, but not all subjects are available from all providers. They range from English Literature to Physics, Economics to Music Technology and Classics to Computer Science. The same A Level subject can be offered by more than one exam board and providers can choose which board they prefer to use for which subject.

Students normally choose 3 A Level subjects to study from amongst those offered by their provider. Some students will study 4 (and very occasionally, 5). The ability to do this varies by provider and it can be more common for some subject combinations. For example, Further Maths is often added as an extra 4th A Level alongside a combination such as Maths, Physics, and German. Aside from any complications due to timetabling, there are not normally any restrictions placed on the combination of A Level subjects by providers. For example, one student may choose Chemistry, Maths and Physics while another chooses Art, French and Physics. However, students are often advised to keep any future university choices in mind because certain A Levels are required for some university study (for example, prospective Medicine students will be advised to take Chemistry).

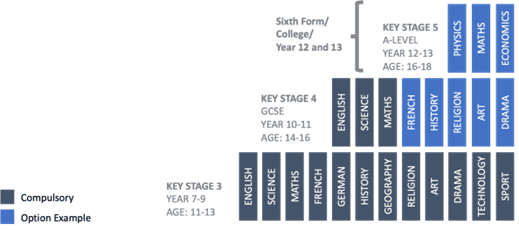

Figure 3: A level entries by subject in 2023. Data Source: JCQ (2023). Image: Johnson et al. (2023).

Prospective Economics undergraduates will require A Level Mathematics for some degree programmes, but this is certainly not true for all courses. A Level Economics is an increasingly popular A Level, becoming one of the top 10 A Levels in 2023 (see Figure 3) but it is not widely available across most providers and it is not required for any UK degree programme (Discover Economics (2024), Paredes et al. (2024)). Similarly, A Level Further Maths is also not universally available and is not required for any Economics undergraduate programmes, although a few universities express a preference for students to take Further Maths if the opportunity is available at their provider.

How are A Levels assessed?

A levels are typically assessed through a number of exams, or coursework assignments, or a combination of the two. A student will need to take multiple assessments to achieve the A level qualification in a particular subject. In AQA A level Economics, for example, students sit three exams at the end of their two year course. Each exam is 2 hours long as covers a different area or skill (Markets and Market Failure, National and International Economy, and Economic Principles and Issues). This means a total of 6 hours of exams for the A level in this subject, and approximately 18 hours of exams across a normal 3 A level course load.

How are A Levels graded?

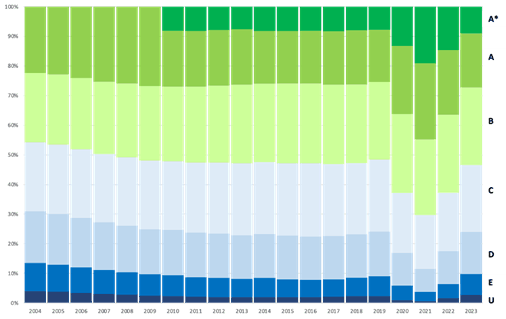

Upon passing an A Level a student is awarded a grade A*, A, B, C, D or E (where A* is the highest grade achievable). If a student does not pass then they are awarded a grade U (unclassified). The grade is decided by the exam board, which sets and grades (or in the case of coursework, moderates) all assessments (AQA, 2018). The overall distribution of grades for each subject is decided on by the exam boards and monitored by the regulator Ofqual.

Figure 4: Distribution of A level grades across all subjects in England in 2023. Data Source: JCQ (2023). Image: Johnson et al. (2023). Note (i) the A* grade was first awarded in 2010 and (ii) assessments were conducted and regulated differently during the Covid-19 impacted years of teaching.

A student receives one letter grade per A Level so a students’ overall performance (and university offers) are normally expressed as a set of three letters such as ABB or A*BC. Sometimes universities will express their standard offer not as three letters but instead in terms of UCAS points such as “120 tariff points”. UCAS (the UK’s central coordinator for university applications and admissions in the UK) has a tariff point table (UCAS, 2024) which gives points for different qualification at different grades. Under this system, an A Level at grade A* is 56 points, A is 48 points, B is 40 points and so on. The points system makes it easier to combine and compare different types of qualification. This can be particularly important for students who combine A levels with other qualifications for university entry.

Are A Levels the only qualification?

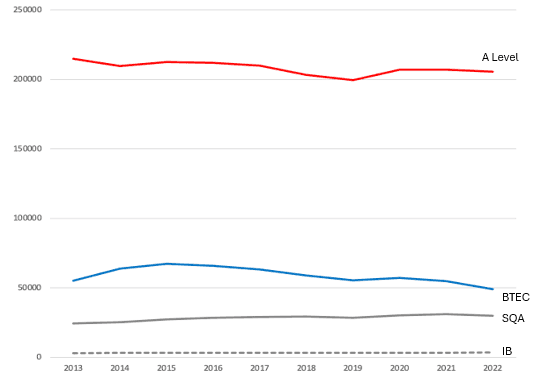

A Levels are the most common qualification used by 18 year olds for university entry (see Figure 5 below) but there are many other qualifications and routes which can be used to enter an undergraduate programme.

Figure 5: University applications by qualification type (A Level, BTEC, SQA and IB) in 2022. Data Source: UCAS (2022). Image: Johnson et al. (2023). Note some qualification types are not shown here (eg. A levels in combination with BTECs).

BTECs (and the incoming T-levels which will replace BTECs (Department for Education, 2023)) are career focussed, technical qualifications in a range of subjects. Some students will combine A Levels with BTEC qualifications. Students in Scotland will study Highers and Advanced Highers (SQA) and a smaller number of university entrants in the UK will have completed the International Baccalaureate (IB). Other entry routes include Access to HE courses, which are courses designed as a route to higher education for people without traditional qualifications. Each of these courses is a Level 3 course on the National Qualification Framework, but the structure, number of subjects studied and assessment style can be very different to A Levels.

Impact on Economics teaching at university

This section is written to give context as to why students can begin their degrees with certain beliefs regarding how to approach their studies. Economics undergraduates arrive at university having studied a diverse range of A Levels, with some of them having taken an A Level in Economics and others not. Some of the information in this section is relevant specifically to students who have taken the A Level in Economics and some of the information is relevant regardless of what A Levels the student has taken.

Past papers and examiners' reports

As stated above all A Level exams are set by exam boards, also referred to as awarding bodies, such as AQA, OCR, or Edexcel. These exam boards provide a wealth of material to both A Level teachers and students to prepare them for their exams. This will include many years of past exam papers, detailed mark schemes for each of these papers and examiners' reports. These are freely available, with only the most recent assessments protected (for example, see this bank of assessment resources for AQA A level Economics). The past exam papers will be very similar to the format of the exam that the students will sit and will be used extensively as revision practice and in mock exams. The examiners' reports will provide detailed explanations on how the students who sat the papers performed on each question — including real examples of students' work — and highlight where students commonly made errors.

Throughout their A Levels students are therefore exposed to a large amount of preparatory material of a very similar nature prior to their actual assessment. Since the A Level syllabus is also finite, this means students are able to effectively practice for exams and cover most of the required material through the practice of past papers. This is in sharp contrast to undergraduate teaching where syllabi are frequently adjusted or expanded, and assessment types updated.

Advice for Economics lecturers:

- Make clear from the outset how they are expected to prepare and what material will be available to students to help prepare them for their assessments (for example, in a course unit outline). Highlight the materials students need to focus on, such as weekly problem sets, or anything which is critical for assessment preparation.

- Explain to first year students that assessments are set and marked in a different way to some secondary school systems. Make it clear from the beginning that the assessments are designed by the staff on the module who are actually teaching them and that banks of past papers are not a good way to prepare. Reassure them the assessment is designed with this in mind, and marked accordingly.

Opportunities to remark and resit

If a student is unhappy with their A level grade, they have a number of options available. They can request to see their original script, they can ask the exam board to check the script was processed correctly and in some cases the student can also ask for the exam to be remarked. Some exam boards also offer priority routes to provide a quicker review. In many cases, teachers or school staff will also help them to navigate these processes. Ultimately, if a student is unhappy with the outcome, then they can choose to resit the A level at the next opportunity to try and improve their grade.

At university, the options to do this are much more limited. Exams can often only be regraded if it can be shown a regulation was not followed or there has been a clerical error. It is normally only possible to retake an exam if a module was not passed on the first attempt and any retakes may be subject to strict caps (eg. restricting the final module mark to 40%). Since the student is often appealing against a decision their own lecturer made, they also often need to seek support from a more independent body such as the Students’ Union. If students only understand this as they first encounter university exams, then it can cause a lot of confusion at a stressful period in the year.

Advice for Economics lecturers:

- Try to make students aware of how exam processes, appeals and retakes work early on in the year, and repeat them a few weeks before major exam periods. These regulations can often be dense so try to highlight the most important things such as “what happens if you don’t pass a module” and “how to submit extenuating circumstances and when”.

- Don’t be surprised or offended if a student asks you “Can I have a re-mark?”. This is a more common question at A level, linked to the national exam board practices. The student might simply not understand how the university processes work and that they might need to speak to the Students’ Union instead.

- Be careful of the terminology you use and be aware that students may misinterpret key terms. For example, when talking about ‘exam boards’ you may mean a faculty level meeting, whereas the student understands it to be a body external to the university.

Essay structure and writing style

Across the exam boards for the Economics A Level there is a requirement to write a 25 mark “essay” in the final exam completed under timed conditions. This is an example from the AQA 2022 Paper 1 Essay Question (Question 12, AQA (2024)):

Evaluate the view that government failure means that government intervention in markets will rarely lead to an improvement in economic welfare.

The essay is marked on four components: Knowledge, Application, Analysis, and Evaluation. A Level Economics teachers spend a considerable amount of class time helping students prepare these answers, including marking drafts and conducting mock exams under exam settings. Lessons will also be given directly on exam and essay technique. Mark schemes for past papers will often break down examples of the different things required for the Knowledge (eg. are the relevant terms defined?), Application (eg. is data used appropriately?), Analysis (eg. are the correct diagrams used to inform the discussion ?) and Evaluation criteria (eg. are some of the assumptions which affect the conclusion of the diagram discussed?). For many undergraduate students this will have been their main exposure to essay writing and essay writing technique for Economics.

Advice for Economics lecturers:

- Don’t be surprised by questions such as ‘How many evaluation points do I need?’ as this was key to the structure of A level Economics essays. Instead, help them understand the style of writing you are expecting.

- Show students examples of essays from previous years to give an indication of the purpose, the structure and expectations of a university essay. Explain to them it may be different to writing they’ve had to do in Economics before and leave time to discuss the expectations in class. Consider adding some examples of professional economics writing alongside so that they can understand the link to future practice in the workplace.

- Provide some guidance on how to incorporate evidence into the writing task you have set, such as which papers or reports to reference and how to incorporate this into their writing. A level Economics writing will typically centre on simple descriptive stats and a basic model so they may be unfamiliar with sources of formal economics writing.

Academic Literature

During the Economics A Level there is no requirement or expectation for students to reference anything during the exam. In terms of external material, A Level Economics teachers will recommend reference websites such as Tutor2u or EconomicsHelp as useful resources for revision and for additional learning resources. It is therefore common for first year undergraduate students to use these websites and to reference content from them in their work.

Advice for Economics lecturers:

- Spend time with undergraduate students explicitly explaining what is and isn’t an academic source prior to their first assessment. This may even involve providing a small selection of references related to an assessment. It is also worth highlighting that reference websites such as those above are not suitable references for undergraduate work.

- Students will also benefit from a brief explanation of the peer review process so they understand why there are differences between non-academic and academic sources.

Diagrams

As well as repeated essay practice, the A Level in Economics will often involve repeated practice and revision of diagrams. During this practice these diagrams will often be drawn in a prescriptive manner e.g. for the Monopoly diagram the marginal cost curves will always follow an upwards tick shape. Students, having practised drawing these diagrams and being repeatedly told that the curves are always drawn a certain way, can then find it challenging when being exposed to these models with different functional forms during their undergraduate studies.

Advice for Economics lecturers:

- Make clear the underlying assumptions of each model that is introduced. Consider showing them several different functional forms early on and ask them to discuss possible examples for each set of assumptions.

- Using interactive models through tools such as econgraphs.org can be an efficient way to do this in class, without necessarily needing a detailed understanding of the maths upfront.

Conclusion

The transition to university can be challenging for students for many reasons, and a change in both the teaching delivery and assessment can be part of this. For first year course directors and programme directors it is important to keep in mind the prior educational experience of their students and how this may impact their expectations of their undergraduate studies. It is therefore important to clearly explain to students how to approach studying at degree level and how to prepare for their assessments. As this resource focuses only on A Levels this does not cover the wider variety of experiences international students will have had prior to their university education.

References

AQA (2018), How we set grade boundaries. YouTube. Available at https://youtu.be/B95toS5xPYk?si=Ul6i65vuIr-RyenC (accessed on 31/07/24).

AQA (2024), A-level Economics past paper 1. Available at https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/sample-papers-and-mark-schemes/2022/june/AQA-71361-QP-JUN22.PDF

Department for Education (2023), Introduction of T Levels (2023), Department for Education Policy Paper. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introduction-of-t-levels/introduction-of-t-levels (accessed on 23/04/24).

Discover Economics (2024), Course Requirements for Studying Economics. Available at https://www.discovereconomics.co.uk/course-requirements (accessed 23/04/24)

JCQ (2023), Examination Results Archive, Joint Council for Qualifications. Available at https://www.jcq.org.uk/examination-results-archive/ (accessed on 31/07/24)

Johnson, A. (2022), Structured Transitions. Presentation at Annual Teaching Workshop, Department of Economics, University of Southampton.

Johnson, A., Proud, S. and Thornthwaite, D. (2023), “An exam by any other name...": Understanding the role of A-levels in students' assessment expectations. Developments in Economics Education Conference 2023, Economics Network.

Paredes Fuentes, S., Burnett, T., Cagliesi, G., Chaudhury, P. and Hawkes, D. (2024), Who Studies Economics? An Analysis of Diversity in the UK Economics Pipeline, Royal Economic Society. Available at https://res.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Who-studies-economics-Diversity-Report.pdf (accessed 23/04/24)

QAA (2024), QAA Subject Benchmark Statements. Available at https://www.qaa.ac.uk/the-quality-code/subject-benchmark-statements (accessed on 31/07/24)

UCAS (2022), UCAS Undergraduate End of Cycle Data Resources 2022. Available at https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-end-cycle-data-resources-2022 (accessed on 01/09/23)

UCAS (2024), UCAS Tariff. Available at https://www.ucas.com/advisers/guides-and-resources/information-new-ucas-tariff-advisers (accessed on 23/04/24)

↑ Top