Lory Barile, University of Warwick

Andrew Mearman, University of Leeds

Anthony Plumridge, University of the West of England, Bristol

(Authors listed alphabetically)

Edited by Caroline Elliott, University of Warwick

Published August 2023

1. Introduction

This Handbook chapter addresses the challenge of incorporating sustainability into Economics curricula. It has been revised to incorporate new developments, particularly behavioural economic perspectives.

The need to incorporate sustainability has increasing urgency, given some of the extremely concerning projections from the IPCC and other reports about planetary boundaries being breached. Demand for an economics that incorporates sustainability remains high among current students, and if the School Strikes are an indicator, future students too. Increasingly we understand that the climate emergency is also a global health emergency. We constantly see its direct effects via heat and extreme weather events, but also its indirect effects on health, including new increasing pathogens, climate refuges, food supply chain changes and mental health. Thus, we recognise that environmental economics and climate change speak to many different economics subdisciplines, including labour, public, health, and behavioural economics, as well as economic history and industrial organisation.

Recent research (see Hickman et al., 2021) has also shown that climate anxiety plays an important role on children and young people having a negative impact on their daily life and functioning. Furthermore, climate anxiety and distress seem to be correlated with perceived inadequate government response and associated feelings of betrayal.

Political pressure has increased, via established political processes such as governments making commitments (NDCs) at successive COP meetings and the unconventional (for example, by Extinction Rebellion), and some legislative bodies have declared climate emergencies and/or NetZero policies. Globally, green new deals in various forms have been proposed by the New Economics Foundation, World Wildlife Fund and the Whitley Fund. The UN launched its seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), covering economic, social and ecological dimensions simultaneously. The EU Council has formally adopted education for sustainable development (ESD) as a policy goal (Council of the European Union, 2010). In recent years, European countries performed well in relation to quality education (SDG No. 4, where ESD is incorporated as target 4.7) with 16 EU countries scoring above 90 out of 100 (from a scale that considers 0 = the worst, and 100 = the goal achievement). However, major progress and guidance are needed to strengthen ESD in education systems (European Commission, 2022).

Businesses and training organisations want people with the relevant skills. The QAA has launched ESD skills, including systems thinking, critical thinking and normative competence. Universities now have clear climate plans, commitments to decarbonise and are considering sustainability in all their operations, often via dedicated sustainability teams.

1.1 Economics and sustainability

As laid out in the new Economics Subject Benchmarking statement (QAAHE, 2023), a specific purpose of Economics degrees is that

“graduates develop capacities that enable them to cope with and attempt to create solutions for the global crises we are currently facing, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, environmental (in)justice and potential, consequent instabilities reflected in social and economic inequalities. These problems are transdisciplinary and interdependent in nature”.

As such, as well as problem solving skills, they require students to foster critical and creative capacities beyond the application of existing tools and models. The core economics competencies developed in our Economics programmes – for example, assimilation, structuring, analysis and evaluation of data – form a strong foundation for evidence-informed and sustainable policy and provide students with the skills required to engage with sustainability-related topics as they progress and specialise in their subject area. This allows them to develop additional competences (such as systems thinking, and anticipatory thinking) closely aligned with the learning outcomes suggested by the Education for Sustainable Development Guidance produced by Advance HE and QAA (March 2021), which go beyond solely environmental issues, and highlight the need to foster the intertwined nature of the three pillars of sustainability.

Indeed, economics continues to respond in various ways, for instance through wide-ranging reports such as those by Stern (2006) and Dasgupta (2021) in the UK. Ostrom and Nordhaus (2009 and 2018, respectively) won Nobel prizes for work in this area. Meanwhile, new developments in economics offer fresh perspectives on how economists might consider sustainability. One of these, featured in this chapter, is behavioural economics, which offers different ways of conceptualising the individual in relation to Nature, and policy proposals to have positive ecological impact. The 26th Cooperation of Parties (COP26) meeting stressed the need for behavioural change and called for immediate action to tackle the climate emergency. More recently, at COP27, the Egyptian presidency highlighted the need to shift the focus to action on the ground.

Furthermore, approaches informed by systemic analyses have informed policy: these include the much clearer incorporation of ecology into macroeconomic models; and the UK Government approach to valuing infrastructure is now underpinned by a systems of provision approach (Bayliss and Fine, 2020). Yet more approaches, from what some call Social-Ecological Economics, argue that sustainability is incompatible with current capitalism, and/or argue for economic de-growth and present visions of post-growth economic arrangements. These different perspectives illustrate a key point of debate between those who advocate individual behavioural change and others who advocate system change – and a range of others in between – as the route to sustainability.

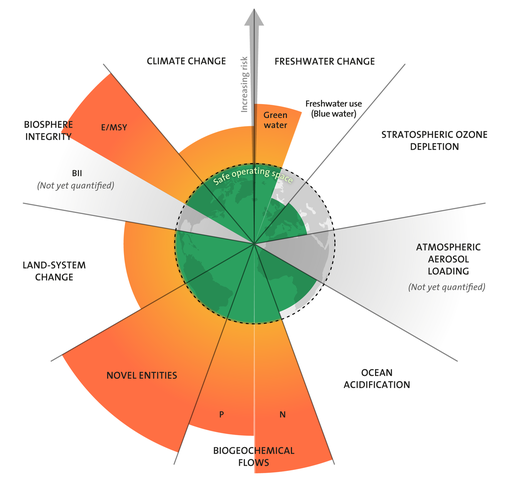

Teaching has now embraced more regularly sustainability since Green (2013) reported that textbooks largely ignored the issue. CORE has placed the economy more squarely embedded in the ecology, even if some critics would like it to go further to include the biophysical. Doughnut Economics, as developed by Kate Raworth (2017), has had a large impact, developing a needed literature to increase awareness of climate emergency. Doughnut Economics echoes the planetary boundaries approach by recognising that there are limits within which economic activity must operate.

The challenge of embedding sustainability is considerable, but also interesting, even for those with no interest in the topic. Why? As will become apparent, the task of placing this issue in the curriculum involves a range of choices for the programme designer; it also requires the teacher to take an inherently multi-faceted, complex and interdisciplinary concept and place it in a disciplinary context. In addition, it forces the tutor to be aware of the pedagogical issues that become acutely manifest: the engagement of the student, helping them through their inevitable confusion, and the achievement of resolving their problems.

Top tip

Consider why incorporating sustainability is important to do. Discuss this with students.

However, there are several reasons for trying to meet these challenges, not least because overcoming them could be personally rather satisfying. Second, given the prominence of sustainability, students are likely to be already engaged with, perhaps enthusiastic about, the topic. Third, given the contemporary context – of climate change, resource crunch, biodiversity loss, food delivery challenges, and so on – dealing with sustainability is arguably important. Fourth, the students will gain tremendously: given the multi-faceted, complex nature of sustainability, students will develop depth of understanding, the ability to weigh up conflicting opinions and value systems and make decisions in the light of them and develop systemic thinking skills. Your students will come out better educated at the end and will develop several future-proofed capacities (e.g., global thinking, lateral thinking, and cognitive flexibility are only some examples). The development of these aspects is also likely to help students be more employable, both in having the relevant sustainability skills and aligning better with employers’ concerns.

↑ Top2. Getting Started

Teaching sustainability involves choices. All teaching does, of course, but given the relative novelty of the subject and the lack of established resource bases, say, compared with core microeconomic theory, there are fewer ready-made guides on how to design sustainability curricula and how to deliver them. Advance HE, for example, provides useful guidance on how to embed sustainability into the curriculum, but not clear examples of how to teach sustainability. That lack of pre-existing structure can be liberating, but also daunting.

However, the choices are unavoidable. There are two main sets of choices to be made. One is whether to integrate sustainability across the curriculum (if it is possible within institutional constraints) or whether to create specialist niches within it. That choice is followed by others about the depth of integration and about the theoretical approaches considered. We shall return to those issues shortly. Before that, the tutor needs to consider what they understand by sustainability. Sustainability is a complex term that addresses the tension between different assets/capital (social, environmental and economic) and combines them into a single concept. This chapter is designed to help tutors make these choices.

Top tip

Use examples to illustrate unfamiliar sustainability concepts: make it personal not abstract. For example, ask students to consider their own consumption patterns, perhaps using a personal carbon or ecological footprint calculator. The WWF has a free option. Ask them to consider their university as a system. Murray (2011) may be a good resource.

2.1 What is sustainability?

A barrier to teaching sustainability is the lack of a clear definition. A common-sense definition of sustainability is that a thing can last. However, what is it that lasts? A firm, an economy, a society, a species, an ecosystem? And when it lasts, does it grow or improve, does it deteriorate, or none of these? The UN World Commission on Environment and Development generated the Brundtland Report and its definition of sustainable development as:

"development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (WCED, 1987: 54).

However, this still begs many questions: is sustainable development possible? Is it possible to trade off one type of sustainability – say, ecological – against another – say, economic? Are human manufactured goods equivalent to those produced in the rest of nature? Given these questions (and others) it is perhaps not surprising that there are so many definitions of sustainability. This array of definitions can be a further barrier, but also a learning opportunity for students, as they show the complexity of the issues at hand, and that sometimes, single definitions are not available.

A key leader in defining sustainability has been the United Nations. The Brundtland definition (above) has now been supplemented by the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

These goals are significant in themselves, in having UN backing which enables their adoption. The SDGs and their underlying approach also indicate several important elements within the literature on sustainability. The first point to note is that they are multi-dimensional, taking in ecological goals that go beyond preventing climate change, social and economic goals. Here, they resonate with approaches such as that of the Triple Bottom Line (Elkington, 1997), the three pillars, popular among some ESG professionals in businesses, and the ‘Five Capitals’ model (Goodwin, 2003), the five being natural capital, human capital, manufactured capital, social capital and financial capital. The model is the basis of one definition of sustainable development. A further useful definitional distinction is that between weak and strong sustainability (Pelenc 2015). In the former, natural resources are somewhat substitutable by human-made, whereas the latter rejects such substitutability.

It is important that students are exposed to (at least some of) these different definitions, to demonstrate that sustainability is a contested concept. That understanding ought to make it clearer to them why there is so much debate about sustainability. However, the tutor clearly cannot juggle all these balls in the air at once and must make some choices about how they define sustainability in their approach. This choice is also crucial because it will condition the extent to which they might wish to integrate sustainability into the curriculum, whether they take a more, or less, interdisciplinary approach, whether they consider (for instance) economic sustainability alone, and to what extent they wish to incorporate approaches to sustainability which lie somewhat outside the mainstream (for example in ecological economics). Indeed, definitions of sustainability help define the distinction between mainstream and ecological economics: the former favour very weak or weak sustainability, while the latter favour strong or very strong sustainability.

Identifying the components of sustainability is just one step, though. A more important question is how they interact; there is considerable debate about this and one way to engage with it is to consider the range of definitions of sustainability. As we move down the degrees of sustainability, we can see at play quite different views of how the economy and environment relate to each other, specifically whether they are separate systems or somehow embedded in each other, and of the possibility of trade-offs between the two (and with social and other dimensions too). Strong and very strong sustainability both suggest the growing recognition that the economy is embedded in the environment, as well as affecting it; and that trade-offs of economy and ecology are not smooth or trivial.

Goodwin (2003) suggests that for sustainability, the total stock of the five capitals should be maintained although the depletion of one type can be compensated for by the increase in others. For example, lost agricultural land (natural capital) could be replaced by a shopping centre (manufactured capital); or forests could be replaced by carbon capture and storage power stations. But this substitutability is frowned upon by adherents to stronger views of sustainability. However, it should be noted that mainstream economics is concerned with the flow of resources into the economic system while the discourse of sustainability focuses on stocks and the rate of depletion or degradation.

One approach that takes this view is Doughnut Economics as developed by Kate Raworth in 2017. Doughnut Economics relates the economy to both social values and goals (the inner ring) and (the outer ring) to a broad range of biophysical markers, reflective of the planetary boundaries approach of Rockstrom et al. (2009). The space between the inner and outer rings is the "safe and just space for humanity, in which inclusive and sustainable development can occur." The doughnut thus represents a system in which there is balance, and in which some trades-off are necessary, but also one in which one cannot trade-off health for education, for instance, or push growth so far as to cause negative ecological impacts beyond the capacity of the planet to cope.

The key idea of the doughnut approach reflects other, perhaps more radical takes on sustainability, in some of which, building on the work of Meadows et al. (1972), growth and sustainability are fundamentally incompatible. These authors hold that sustainability is incompatible with what might be described as ‘business as usual’. The Living well within limits (LiLi) project explores how economies can be re-designed to allow human flourishing without breaching planetary boundaries. The LiLi project uses a ‘systems of provision’ approach that stresses the interdependence of supply and consumption forces, including the importance of culture in driving consumption. For example, Mattioli et al. (2020) discuss structural and cultural barriers to reducing car use.

Other ecological economists draw on thermodynamic approaches and consider the economy in terms of social metabolism, meaning examining it as a system with flows of energy and materials in and out (see Martinez-Alier, 2013), necessary to avoid entropy (see Georgescu-Roegen, 1986 for his own retrospective). Related to that are the concepts of sustainable scale and steady-state economies, both of which are derived from the work of Robert Costanza and Herman Daly, two of the first leading ecological economists. Allied to these approaches are other visions of the economy such as the wellbeing, circular, foundational, de-growth or post-growth, all of which, as their names suggest, reject the typical focus on growth adopted by most economists, politicians and indeed the public.

2.2 Introducing sustainability

Given all the above and its complexity, as mentioned above, introducing sustainability can be a challenge, however, it also presents options. Introducing sustainability to students can be done in several ways. A simple way to introduce the topic could be by means of a word cloud (see Figure 1 below). The advantage of this approach is that the instructor can easily realise whether the students have been exposed to sustainability, which will be evidenced by visualising the relevant keywords (i.e., economic, social, and environmental) in the cloud. Clearly, if this is not the case, the instructor will fill in the gap starting a discussion about the three pillars of sustainability.

Figure 1: sustainability word cloud from Malesios et al. (2020)

Another approach could be to start from an ecological perspective, which sees natural cycles that support ecosystems as the implicit foundation of any discussion of sustainability. An overview of these natural systems is necessary as the basis for exploring the impacts of different economic systems and activities. A few natural cycles could be introduced in early lectures or virtual material. These might include the carbon cycle, making connections with climate change; and the hydro cycle, with a focus on areas of water shortage and the food chain, with discussion of the need for dietary changes if a growing population is to be supported. The advantage of exploring the ecological perspective from the outset is that the concept of sustainability is readily understood. If this approach is followed, the concept can be introduced as the preservation and encouragement of these natural cycles and ecosystems to maintain or increase bio-diversity.

Another approach is to introduce ecological systems when relevant to particular economic topics. However, this leads to a fragmented understanding of what is essentially an interrelated set of natural systems. This might be heavy going for those students not particularly committed to sustainability and be perceived as ‘preachy’. Also, for economists the material might be somewhat inaccessible.

Further, if the tutor wishes to discuss sustainability in a broader sense, they might use the different definitions as entry points into debates about policy, good business practice, etc. Some policy options (for example, the so-called ‘technological fixes’) would be ruled out if one took a strong sustainability approach.

Top tip

Don’t moralise. Admit that a great deal of the discussion around sustainability is value-driven and stress the importance of various different positions on it.

Top tip

Engage students in real problems; including discussing openly the global challenge of sustainability. What can be done? (see Box 1)

2.3 Integrate or specialise?

If a tutor regards sustainability as of fundamental importance, they may wish to integrate it fully into the Economics curriculum. Whether they can, of course, depends on institutional constraints and their own skills of negotiation. Those concerns are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Given that one could integrate sustainability, there are different ways to do this. At one end of the spectrum, a programme might be designed according to problem-based learning (PBL) principles: the problem to be addressed would be achieving an economy that supports a sustainable world, and all the learning would be working towards a solution (see for example, Forsyth, 2010). PBL in its purest form allows the curriculum to unfold as the course progresses.[1] That of course requires great skill on the part of the instructor. Witham and Mearman (2008) discuss some existing uses of PBL in ecological economics courses. That there are some examples of PBL in this area is perhaps not surprising, because sustainability lends itself to a PBL approach: clearly sustainability is a ‘big’, multi-faceted problem, meaning that the course could unfold in a multiplicity of ways. As discussed below (Assessment) one can design coursework assignments or exam tasks around specific problems. That there are some examples of PBL in this area is perhaps not surprising, because sustainability lends itself to a PBL approach: clearly sustainability is a ‘big’, multi-faceted problem, meaning that the course could unfold in a multiplicity of ways. As discussed below (Section 6 on Assessment) one can design coursework assignments or exam tasks around specific problems.

If PBL is a step too far, a course could still begin with the problematic of a sustainable biosphere and then explore the implications of that for an economy via more conventional teaching. Alternatively, sustainability could still be the central theme (or one of a small number of themes) in a curriculum. Where appropriate, all modules would be organised with sustainability in mind. That would involve constructing examples, exercises and assessment that are all concerned with sustainability. Box 2 discusses how to deliver standard concepts such as the circular flow of income with added sustainability content. Such tools would be useful even if sustainability were not a central theme, but instead was a topic which needed to be included in all modules. This last form would be the weakest form of integration, in which sustainability is tacked on to a standard module, often at the end. Section 3 below discusses a standard introductory and one standard intermediate economics course into which examples and applications from sustainability are incorporated easily.

In the strongest forms of integration, students may learn all they need about sustainability simply by doing other modules. However, in those cases, and certainly in weaker forms of integration, students may have had their interest in sustainability stimulated and desire more specialised, detailed knowledge. So, even if a student has been on a programme that integrates thoroughly sustainability at undergraduate level 1 (and/or 2), they might desire specialist modules at level 2 and/or 3. At this point, the choice for the tutor becomes one of which approaches to choose. Again, this may reflect their understanding of sustainability. Those who understand sustainability more narrowly may choose to deliver sustainability solely according to mainstream principles, as found in standard treatments of environmental and/or natural resource economics. Those who take a broader view of sustainability may wish to deliver an ecological economics perspective. In this latter group, as indicated above, it may be possible to begin with a discussion of a sustainable biophysical ecosystem and derive the economics from it. A third alternative would be to try to deliver the two approaches in parallel or debate. Such an approach presents many challenges but may also yield many benefits (see for instance Mearman (2017) on heterodox economics and pluralism).

The main body of the chapter examines in detail how these different alternatives could be delivered. Section 3 explores ways in which sustainability may be taught in standard economics modules. Sections 4 and 5 discuss different variants of specialist courses on the environment or sustainability: Section 4 discusses a course on economics of the environment, with sustainability emphasised, in which environmental and ecological economics perspectives are compared. Section 5 discusses a course in the economics of sustainability. Section 6 concludes, discussing issues related to Assessment.

Top tip

Don’t try to shoe-horn in too much material. The course you create must remain coherent and varied.

3. Teaching sustainability in a standard core module

The first available way to integrate sustainability into an economics curriculum is simply to tack it on as a subject at the end. However, in practice such topics tend to get dropped, or not included in assessments. A more effective way to integrate sustainability – though requiring greater co-operation from staff – would be to use examples from sustainability. Table 1a outlines an introductory economics course, taking in microeconomics and macroeconomics, into which applications to sustainability have been added. The table presents possibilities for inclusion: tutors can pick and choose topics depending on how deeply they wish to explore sustainability. The sustainability topics do have some logical progression, but they could be taught independently.

First, a caveat: the lay out below could be accused of looking how an introductory course used to look, before the advent of CORE (Curriculum Open-Access Resources in Economics), which takes a different approach. Instead of explicitly proceeding in a series of theoretical topics or concepts, CORE tackles real-world issues, including examining relevant data. Indeed, one of the issues it addresses is sustainability. So, under CORE the layout of the course could be quite different, with sustainability as its own topic. This does, of course, raise the possibility that sustainability is treated as a separate topic rather than one that is embedded. However, even under the CORE framework, students are gradually exposed to theoretical concepts, so laying out a series of concepts and their sustainability augmentations as in Table 1a would remain applicable.

Table 1a: Introductory economics course

| Microeconomics | |

|---|---|

| Topic | Sustainability augmentation |

| Scarcity; ‘the economic problem’ | Scarcity: absolute versus relative |

| Decision-making | Multiple ethical bases: triple bottom line (see Elkington, 1997); Multi-Criteria Analysis (MCA) versus Cost-benefit Analysis (CBA): See Box 3 |

| Markets: supply and demand | Carbon markets; oil market (could include ‘peak oil’) |

| Demand theory; elasticity | Effect of a tax on petrol; road charging |

| Theory of returns and costs | End-of-pipe technology (adaptations of existing plants to reduce pollution) and costs |

| Theory of the firm | Increase of resource/raw material/energy costs |

| Market structures | Joint profit maximisation – fishing and maximum sustainable yield |

| Market failure | Externalities of pollution, climate monetary/non-monetary policies (e.g., taxes vs subsidies vs nudges) |

| Micro policy | Carbon rations, petrol taxes; optimal amount of pollution; carbon taxes |

| Macroeconomics | |

|---|---|

| Topic | Sustainability augmentation |

| Circular flow of income | Circular flow extended to include biosphere (see Box 2) |

| Macroeconomic objectives | Sustainability as an objective; an extra trade-off (see Box 4 on recent macroeconomics of sustainability) |

| Economic growth | Sustainable development; alternative measures of well-being, such as Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), Happiness indices, and the Happy Planet Index (HPI) |

| Keynesian macroeconomics | Green stimulus packages, Green New Deals |

| Unemployment | Green jobs |

| Inflation | Price of green products; finite resource cost inflation; backstop technology as a response to inflation |

| Money demand and supply | Green economics treatments of money as debt; carbon as a currency; local currencies |

| Monetary policy | Green ‘quantitative easing’; ‘green bonds’ and other aspects of ‘green finance’ |

| Fiscal policy | Green stimulus packages; carbon and pollution taxes |

| International trade | Transport costs; global value chains; COP; localism versus globalism |

| Exchange rates | Carbon trading markets |

Some of the sustainability topics included are easy to include, whereas others require more ingenuity. Examples of the former are the discussion of the effect of a tax on petrol as an example of elasticity; the carbon market as a market to study; the current debate on the use of monetary/non-monetary interventions with brief reference to green nudges (and their ethics); and the treatment of pollution externalities. On the macro side, the effect of natural resource costs on inflation, the use of fiscal policy for green stimulus, and the measurement of standards of living are also simple to introduce. In the category of more difficult topics would be those that require conceptual shifts, such as the discussion of multiple ethical bases, joint profit maximisation, and sustainability as an economic objective (see above; and see Box 4).

Top tip

Utilise the extensive range of software packages available. See Box 6 for some examples.

All would involve the commitment of some time by the tutor. Even more challenging (as hinted at by the discussion of multiple ethical bases) can be ventures into other disciplines. Examples are the extended circular flow of income (see Box 2), end-of-pipe technology and its effects on costs, green treatments of money (see Scott Cato, 2008: ch. 5), ‘green’ quantitative easing, and discussions of geological theories, such as peak oil. Whether or not and how these get taught will depend on how much time is available, the willingness of the tutor, and the availability of relevant supporting resources. As in Table 1b below, the topics above can be delivered either as an entire suite, or more likely, selected to enrich a standard module, alongside examples from other relevant broad topic areas.

The extended circular flow model has a natural resource stock located at the centre and the flows of materials and services to and from the household and productive sectors indicated by arrows. An approach that has proved successful is to present the conventional circular flow in a lecture and ask where the natural environment and ecosystem services are. It is conventional for students to answer that these are contained within land. Ask the class for examples of the inputs that come from land. Usually, students ignore the ability of the natural environment to provide waste assimilation services. They also ignore the waste assimilation and amenity services provided to households. That omission is the justification for making these ecosystem services explicit by adding to the diagram as above.

Clearly at the introductory level there is plenty of scope for examining sustainability issues. At the intermediate level, this is also true. In this case we shall discuss an intermediate microeconomics course with sustainability material included. One could of course also construct an intermediate macroeconomics course augmented for sustainability. The issues of integration, resourcing, specialist knowledge required, and time constraints are present as in the case of the introductory course. In some respects, they are even more acute because the technical level of the material is higher. In other respects, though, integration of sustainability is just as easy, if not easier. Table 1b outlines an intermediate microeconomics course augmented for sustainability. As above, although it is possible to deliver all these augmentations, that is not necessary. The suggested discussion topics can be inserted individually into a conventional course.

Table 1b: Intermediate microeconomics course

| Topic | Sustainability augmentation |

|---|---|

| Consumer theory | ‘Economic human’ vs. ‘Real-human/homo realitus’ vs ‘Eco-human’ (see Becker, 2006); willingness to pay (WTP), willingness to accept (WTA); cost benefit analysis (CBA) |

| Analysis of choice under risk and uncertainty | Problem of non-probabilistic (Knightian) uncertainty? Question the value of the expected utility hypothesis under uncertainty |

| Analysis of investment appraisal and long-term decision making | Assumptions made? Discounting and the environment? Precautionary principle |

| Isoquant theory | Questioning the nature of capital; natural capital; the shape of isoquants |

| Theories of the firm | Alternative goals: business ethics, including CSR and, ESG; sustainable business models (see Bradley et al, 2020), competition and sustainability |

| Labour markets | Basic income schemes |

| Market structure and efficiency | OPEC and oil prices |

| Game theory | Climate change negotiations and compliance –see discussion of classroom games. |

| Price discrimination | Peak flow pricing |

| General equilibrium analysis | Welfare effects of climate change |

| Public goods and merit goods | Environmental impact evaluation, green nudges, climate policy vs climate regulation |

| Externalities and their internalisation | Pollution and its abatement, green nudges, climate policy vs climate regulation |

For example, once students have discussed consumer theory, it is an easy step to discuss the notion of an eco-human (cf. economic human) whose concerns with sustainability may override utility from consumption of some goods; or for whom preferences are lexicographic in favour of sustainably-produced goods.

Both can then be compared to ‘Real-human/homos realitus’ – a concept derived from behavioural economics – whose concern with pro-environmental behaviour is affected by behavioural biases (i.e. status quo bias, framing effect, overconfidence, licencing effect, confirmation bias, salience, bystander effect, sunk-cost fallacy, carbon footprint illusion) which prevent them to engage with and meaningfully act on climate related issues (see e.g. Barile, 2022; and Luo and Zhao, 2021; and Xie et al., 2019). Most of these biases are documented in the literature (see e.g., Hoggett (2019) and Marshall (2015)) and contribute to explaining why it has been difficult to build consensus around climate change not only in the scientific community (e.g., cognitive biases such as present bias, framing effect, bystander effect and sunk-cost fallacy are relevant here) but also among citizens (e.g., in addition to cognitive biases, perception biases such as confirmation bias, and overconfidence may play a role in this context). This is also exacerbated by climate mis/disinformation that is currently challenging climate action. Although the reality of the climate crisis is an undeniable truth, widely documented by the scientific community, climate deniers promote doubt about the existence, impact, and anthropogenic causes of climate change (see Lynas et al., 2021). Their tactics range from misrepresenting scientific data to accepting severe climate change but denying the possibility of meaningful action or advocating ineffective action (Oreskes and Conway, 2012).

Climate mis/disinformation has been recognised as a threat for outcomes of the Cooperation of Parties meetings. Therefore, during COP26, institutions including WWF International and the Centre for Countering Digital Hate were among 250 signatories to an open letter to the UN asking for action on climate misinformation. The letter, now available at Climate Action Against Disinformation (CAAD) and re-proposed to the COP27 Presidency, Country Delegations and UNFCCC, calls on world leaders and social media platforms to act against climate mis/disinformation. This could be used as a starting point to initiate a debate about climate deniers. The Climate Attribution Database then provides a useful tool to search for scientific research organised by thematic areas, which could be used to show students not only the causal link between human activities and climate change, but also how changes in the climate affect humans and ecosystems, including food security, productivity and labour supply (by means of impact attribution). Similarly, the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative offers attribution analyses on extreme weather events, and represents another invaluable source of information in this area.

In relation to other topics, indifference curve analysis can be used to discuss willingness to pay and willingness to accept (see for example, Perman et al., 2003: ch. 12) and introduce the status quo bias which leads to individuals’ inertia to act. Notions of compensating and equivalent variations help illustrate cost benefit analysis. The topic of valuation is discussed further in Box 5, which also discusses cost benefit analysis; and the software package CBA Builder (Wheatley, 2011) is discussed in Box 6. The analysis of choices under risk and uncertainty can be linked to the discounting debate and the concepts of weak/strong sustainability. It may offer an opportunity to better understand how ‘homo realitus’ deviates from rational behaviour and exponential discounting with present bias and hyperbolic discounting. It also helps introducing ambiguity aversion and interesting reflections on the need of discounting all goods the same (see Goodin, 1982), and using different discount rates for different assets depending on concerns regarding future generations (for a discussion on dual discounting see e.g., Kula and Evans, 2011; and Almansa and Martinez-Paz, 2011), which ultimately affect the pure rate of time preference in CBA.

For some of the topics shown in Table 1b the sustainability aspect is very clear: for example, general equilibrium, public and merit goods, and externalities are often taught anyway using environmental examples. For some of the other aspects it is also fairly trivial to introduce sustainability. For instance, OPEC is often used as a case study in oligopoly. The sustainability angle could be extended to discussing broader aspects of OPEC strategy, such as linking production to reserves. The theory of peak oil could be discussed at this point.

Sustainability also lends itself to a discussion of price discrimination. An interesting exercise in price discrimination is to present students with apparent examples of it – such as fair trade versus other coffee, feed-in electricity tariffs, organic versus non-organic food – and discuss whether (and why not) these are true examples.

Modelling climate change treaty negotiations and compliance could also be a good vehicle for teaching game theory. It is easy to use a simple Prisoner’s Dilemma to discuss the likelihood that one country would renege on climate deals; and then discuss why this analysis might explain why climate deals are difficult to negotiate. It is also easy to incorporate discussions of sustainability into the topics of investment appraisal and long-term decision making. Clearly, as discussed in Box 5, discounting is a crucial feature of valuation of ecological objects, and of CBA. Some students may appreciate the chance to discuss concrete cases of a non-financial nature; others may wish to discuss what discount rates ought to be. Ackerman (2009) provides an illuminating discussion of discount rates from the viewpoint of sustainability. More difficult for economics tutors to discuss might be questions of the nature of capital (and therefore substitutability); and non-probabilistic uncertainty. Yet, uncertainty of this type is pervasive in sustainability questions. Sensitivity analysis can assist us in imagining future scenarios, but it is instructive for students to consider what they would do when they simply do not know future risks.

3.1 Introducing valuation to students

This is a very rich area for exploring issues in applied economic methodologies and for discussing underlying theoretical issues. As an introductory exercise, groups of students can be asked to choose an environmental asset to value and then be given roughly fifteen minutes to sketch a valuation methodology they might apply. Each group then describes their methodology, and this leads to some interesting discussion of problems and challenges.

For examples, in introducing the topic, students can be asked to think about the distinction between environmental goods and bads. Economic agents consider environmental goods as items that increase their utility and for which they prefer more to less (e.g., water quality and rainforests). By contrast, environmental bads tend to decrease their utility as they increase (e.g., noise, and water pollution). Clearly, some environmental goods and bads are mirror images of each other – e.g., river water quality (a good) and river water pollution (a bad).

Environmental valuation is considering the increase (decrease) in utility from an increase (decrease) of an environmental good or the increase (decrease) in utility from a decrease (increase) of an environmental bad. This is equivalent to say that it aims to measure the change in utility from a one unit change in the good or bad. This may lead to an interesting conversation about compensating variation (CV) (i.e., the amount of income an individual would pay to keep their utility as it was before introducing a change), and the equivalent variation (EV) (i.e., the amount of income an individual would accept to avoid the change), and how they link to WTP and WTA when considering a good or a bad.

Students can then be asked to reflect on how accurate this measurement could be. It is certainly difficult to measure environmental goods/bads, especially because most environmental goods are public goods, and most environmental bads are negative externalities, so it is very hard to come up with an accurate estimate of environmental amenities/assets and the benefits and costs of preserving them. However, not monetarizing environmental goods/bads means not placing a value on them, which negatively affect CBA (as many projects will not pass this appraisal exercise).

Cost Benefit Analysis (see Box 3) is very useful for students to consider. It has clear policy implications and usefulness and deals with concrete examples. CBA is used in a variety of contexts within government. It also serves as an excellent pedagogical tool, as it can stimulate discussion about what and how to measure objects, whether they are amenable to measurement and, if not, how to deal with them. CBA Builder (Box 6) is also a good tool for teaching and for students to master Excel. It is therefore useful on any applied microeconomics course. Further, attitudes to CBA are also one of the division points between environmental and ecological economists: the latter are sceptical of CBA and at best favour cost-effectiveness analysis.

↑ Top4. Teaching a contending perspectives course on economics of the environment

All the course structures contained in this chapter are of course simply materials from which to draw. Above, one could choose to teach the courses as laid out or pick elements to include in one’s own introductory or intermediate microeconomics courses. Or they could simply be a set of concepts that are significant in this sphere. Both courses are core to the curriculum and are ideal if one’s goal is to integrate sustainability into the curriculum. However, if one chose instead to create specialist courses, or if the goal was to allow students to build on earlier core courses, a different model is required. The next two sections discuss two possible options: one is a course on economics of the environment; the second (Section 5) is on economics of/for sustainability.

The first is presented again as a set of possibilities. There are several ways in which one could teach a course on the economics of the environment. A standard approach is to teach ‘environmental economics’. Such a course would emphasise the principles of the left column in Box 7. This draws on literatures called ‘environmental economics’ and ‘natural resource economics’, which tend to be constructed on conventional economic principles. As an alternative, or complement, one might teach ‘ecological economics’, a literature in which the items in the right column of Box 7 are emphasised.

Again, there is a choice about to what extent one employs ecological economic principles and concepts. One could integrate them into an essentially conventional course on environmental economics, either extensively or piecemeal. Or one might choose to teach from the ecological economics perspective. In terms of sustainability, this could be justified if one agreed that ecological economics is the ‘science of sustainability’ (Costanza et al., 1991).

A third alternative is to teach both ‘environmental economics’ and ‘ecological economics’ in debate or, in parallel, i.e. as complementary or contending perspectives. Again, the instructor faces a choice of how to do this. In the course shown below (see Table 2) the contrast between the two views of economics is presented almost immediately.

Table 2: Contending perspectives course – environmental versus ecological economics

| Topic | Emphases |

|---|---|

| Current state of the world | Major issues: resource depletion, global warming and climate change; pollution; combined problem of population growth and inequality |

| Two views on economics | See Box 7 on ecological and environmental economics |

| Ecosystems | Notions of materials balance; keystone species (Paine, 1969 is the seminal piece) |

| Thermodynamics | Laws of thermodynamics |

| Sustainability | Damage functions, assimilative capacity |

| Growth and the environment | Environmental Kuznets Curve |

| Externalities and property rights | Optimal level of output and pollution; policies to achieve them |

| Cost benefit analysis | See Box 3 |

| Ecosystem services – valuation | See Box 5 |

| Sustainability and biodiversity | Quasi-option value see Box 5 |

| Human populations and ecology | Food; agricultural sector; diet |

| Resource use and renewability | Finite and renewable resource models – MSY Hotelling model |

| Trade and pollution | Off-sets; UK exporting ecological/carbon footprint via FDI |

| Climate change | Carbon footprint; the Stern review; impact of climate change |

| Adaptation and resilience | Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology; localism; flood defences; genetically-modified crops |

The course begins by outlining the current world situation. It is hoped that this would stimulate interest. It is important to stress at that point that there are several issues to consider. Whilst it is important to bear in mind that there are dissenters to the near-consensual view on anthropogenic climate change, it is unproductive to get stuck on that issue; it is better to move on to questions of biodiversity loss, resource depletion and the like.

After this opening follows the discussion of the two contending (or complementary) perspectives. Again, at this point, the instructor must choose whether to see the perspectives as arguing over who is correct (contending) or as both providing insights that fit with those of the other (complementary). This choice affects the entire delivery of the course and is particularly acute in its assessment. Students can be asked to consider a problem from both perspectives and consider which one is better, how to use both, or even be invited to supersede each in a novel combination. Whichever of these routes is taken, there is a danger of confusing students; however, these dangers can be reduced if the contrast is introduced early in the process, and if it is reinforced often, particularly in assessment. Thereafter, the course is a series of topics on which each perspective has a bearing to differing degrees.

Top tip

Using multiple perspectives can be challenging to students. Guide them carefully, but do not push them through the contrasts.

It is true that much of the early material is from natural science and it would be unreasonable to expect economics instructors to be au fait with many of them. For example, most would not have a command of the laws of thermodynamics; however, some rudimentary knowledge of them would be required. The crucial point to get across is of entropy and of how it is necessary to have systems that are open. Similarly, it requires an ecologist to understand fully the nature of ecosystem services; however, the main point of this discussion is to make clear the roles of carbon sinks, etc. and to encourage students to think more broadly about, say, a field than simply its marketable value. Fortunately, standard texts in ecological economics deal with this need by offering definitions of concepts such as damage functions, assimilative capacity, and the like.

Many of the other points have already been discussed and draw on the material elsewhere in the chapter. On many of these there is considerable debate between environmental and ecological economics. For instance, on valuation (see Box 5) while ecological economics acknowledges that conventional valuation methods such as WTP and WTA, hedonic pricing, etc. are useful they are more sceptical about their value. Ecological economists are more likely to argue that vital ecosystem services are not amenable to valuation at all, or at least only with considerable scope for error.

The scope for debate continues throughout the course, finishing off with the highly contentious topic of climate change and the controversial Stern Review (2006). The Review is a very useful pedagogical device because it is possibly the most thorough application of techniques of economics of the environment to questions of sustainability (and certainly the most well-known) so provides an excellent vehicle via which to reflect on the rest of the material in the course. Also, the Review is useful because it has been vigorously opposed from both sides of the debate. For example, Nordhaus (2007) has argued that the discount rate assumed by Stern is too low. Dasgupta (2007) is concerned that Stern’s discount rate does not consider sufficiently intragenerational equity. Ackerman (2009) criticises the attempts at valuation within the Review. An obvious capstone to this course would be a debate between groups of students on the Stern Review, in which they are expected to draw on relevant concepts from the course.

↑ Top5. Teaching an applied course on sustainability economics

The above course is one on economics of the environment, in which special attention could be put on sustainability. However, one could go a step further and construct a course specifically on sustainability economics, perhaps based on the programme of Baumgartner and Quaas (2010), which stressed the ethical basis of sustainability economics and identified efficiency as a goal in the service of environmental justice and included foci such as systems thinking, uncertainty, thermodynamic principles and used input-output models extensively. Courses on sustainability economics remain unusual. The course below (Table 3) is constructed based on one taught by the authors, combined with some other examples of good practice from around the world.

We feel that in a course on sustainability, starting by discussing a sustainable biosphere is unavoidable and desirable. It is essential that students understand the nature of the biosphere, and thence its sustainability, before moving on to consider what economic (and other) systems would be needed to achieve sustainability. One way to approach the question is to lecture about some basic concepts, but then take the main components of the biosphere: soil, marine, hydrosphere, natural forest, wetlands, etc., and divide the class into groups to report back on each part. This could be used as a model for the rest of the course.

Table 3: A course on sustainability economics

| Topic | Tasks or exercises |

|---|---|

| Sustainable biosphere | Group reports |

| Complexity and systems | Complexity game (see below) |

| Entropy and thermodynamics | Energy hierarchy and its appropriate use |

| Circular economies and closed systems | Ellen Macarthur Foundation video; materials balance |

| Definitions of sustainability | Weak/strong sustainability |

| Core concepts in ecol econ – scale, distribution, efficiency | Ecological footprint |

| Economic growth and physical limits | Critique of Environmental Kuznets Curve; notion of critical resources: peak oil; (see LowGrow model in Box 6) |

| Measurement of economic activity | Happiness/HPI discussion |

| Triple bottom line | Ethics; campus walk (see Box 8) |

| Valuing natural capital | See Box 5 |

| Cost benefit analysis | CBA builder (see Boxes 3 and 6) |

| Public goods | Classroom games (see Box 9) |

| Property rights | Notions of commons; anthropo-ecological systems |

| Eco-product design and lifecycle analysis | Biomimicry; show and tell: students bring products to discuss their design and production in terms of sustainability |

| Population | Food; agricultural sector; diet |

One of the consequences of teaching a sustainability course in this way is that students are exposed to economics of complex systems. This exposure may be of benefit in itself. Complexity economics is a relatively young discipline and shares many of its roots and much of its history with ecological economics; yet it has a broader application and has been expounded by significant figures in economics such as Kenneth Arrow and Thomas Sargent. Complexity economics has many implications for both theory and practice. It suggests that even with simple behavioural rules (and hence it has connections with behavioural economics) purposive agents in complex systems can generate unpredictable and potentially explosive outcomes. This has implications for theory – simple rational maximisation becomes less plausible; for methods – agent-based modelling is preferred, and the typical mathematics of economics is regarded as inadequate; and for policy – small policy changes can have large and unpredictable outcomes.

One way to explore this is via a simple complexity game in which students are divided into small groups; each student receives a card with four rules of behaviour on them (at least one of these might be their objective) to which they must adhere. The object of the game is to show the multiplicity of possible outcomes when faced with simple rules.

Top tip

Introduce students to a delicately balanced ecosystem, to understand the complexity of sustainability. Example: a delicately balanced ocean floor ecosystem, whereby bacteria process organic detritus in various ways, some of which lock up carbon and some of which do not, dependent, crucially on the presence of a virus (see The Economist, 2010).

By exposing students to these concepts, complexity economics can benefit them but also alarm them. However, arguably in studying sustainability, complexity is essential because it attempts to capture interconnections and systemic effects in ways that even DSGE models do not (see, for example, Colander et al., 2008). Further, by tapping into modes of thought currently used by governments and other researchers, students are increasing their employability.

The course contains several elements which could be applied to any of the other models above. For instance, the concept of ecological footprint captures the notion of sustainability quite well; and it is empirical and can be evaluated using the REAP software (see Box 6). Under the heading of growth, the macroeconomic consequences of low growth (or even de-growth) could be explored via the LowGrow computer simulation model (Victor, 2008) (see Box 6). A discussion of growth as an objective creates the potential for a discussion of happiness literature, which has much contemporary currency. The literature is varied but includes large econometric analyses so can be a valuable way to explore empirical issues as well as those associated with utility maximising consumers. The issues of valuation and CBA were discussed above, but clearly are important here. A show and tell session, in which students bring in examples of products into class for critical analysis, using life cycle analysis, might be an effective way to discuss that analysis but also asks the students to explore everyday objects from a new perspective.

In a discussion of ethics, following on from definitions of sustainability, is the notion of clashing ethical bases and contesting needs. This clash is captured well by the concept of the Triple Bottom Line (see Section 2.1). One way to explore this concept is via a campus walk or living lab (see Box 8), to demonstrate that each part of the university campus has on it competing demands which must be resolved. Obviously each one would be different and would need to be investigated beforehand.

↑ Top6. Assessment

As has been suggested many times already, assessment is crucial in delivering and generating learning of sustainability. This requires us to re-orient and innovate HE assessment methods to make sure students will be equipped with the relevant sustainable skills and competences. Kioupi and Voulvoulis (2022), for example, propose an assessment framework for evaluating the attainment of sustainability competences and align University’s programmes learning outcomes to sustainability. The framework highlights how different types of assessments can be used as tools to develop sustainability competences in a Postgraduate programme that already had strong links to sustainability. Interestingly, they conclude that further pedagogy research is crucial in this area to understand whether the framework may serve the needs of different types of programmes (e.g., weaker linked to sustainability, or Undergraduate Programmes). We recognise the need for further analysis to guide curriculum review in light of recent policy developments (UNESCO, 2020) that advocates a more holistic approach to sustainability, calling for greater communication and collaboration between universities, businesses and local communities to promote sustainability competences (see also Cook, 2020). However, a few suggestions are provided below.

A key principle is to use assessment to encourage engagement. This can be achieved by basing it around practical problems and objects around the students. As always, where possible, a variety of assessment methods is desirable, reflecting the multi-faceted nature of sustainability.

Given the interdisciplinary content of the sustainability curriculum, students may be exposed to very unfamiliar concepts. Pop quizzes and short tests (including multiple choice) can provide easy ways to test understanding of these new concepts, and to provide instant feedback to the students on their own learning. The classroom exercises can also provide opportunities for formative assessment. For example, students can be asked to present their ideas on how to achieve economies of scale in the most sustainable ways. They might be asked to write a reflective piece on their walk around their campus. Indeed, the university can be a valuable source of material which to study. As an example, in a module called "Sustainable Business" Plumridge asked students to engage in coursework that allows them to study anything relevant to sustainability. In this case, almost two thirds of students choose to evaluate a real company or event. Many of those have been studies of what is going on at our university. The university has the advantage of being personally relevant to the students and therefore engaging; and of course, it is also convenient, and with some minimal co-operation from university facilities and administrative staff, students can gain access to a wide data set on which to base their analyses.

Other classroom exercises could be part of the strategy for formative assessment. One is that of a guided role-play. Students could be asked to consider a scenario and then take roles of various stakeholders in it. For instance, a planning application may have been made for an incinerator. Students could adopt the perspective of a local resident, a planning officer, a local councillor, an environmental assessment expert, and a representative of a group offering the alternative technology of pyrolysis. This exercise helps develop skills of argumentation and presentation, challenges students to think flexibly, and helps them develop an holistic approach to real-world problems. This exercise could be drawn on subsequently, say in the exam: students would be presented with text of a variety of perspectives and then asked to make an assessment. In the latter case, the exercise clearly forms part of formal assessment, but the former could be formative, and could easily be adapted to employ peer assessment and feedback.

Considering summative assessments, multiple choice tests, and exams help testing sustainability literacy (see e.g., Kioupi and Voulvoulis, 2022), whereas essays/reports and policy briefs may allow students to engage with various competences related to sustainability (e.g., systems thinking, dealing with complexity, future thinking, critical thinking, and strategic thinking). As an example, in an Introductory Environmental Economics module, we ask students to produce a policy brief on a specific environmental issue, explain why the problem is important and propose a preferred policy intervention with respect to alternatives, using economic analysis. In this case, we test the knowledge and understanding of the economic framework behind the environmental problem, but in providing alternative policy recommendations, students develop critical thinking competences as well as use a systems approach to understand interactions between policies and humans in different contexts and anticipate pros and cons of the suggested alternative approaches applied to the case study considered.

Top tip

Use assessment as a tool for engagement: some assessment early on ensures that students master crucial core concepts.

Evaluations of real cases tend to be either on current practices of a company or on the environmental impact (via CBA) of a major event, such as mining, or music festivals. The key determinant of success on this project is whether the student embraces and applies an analytical framework. Where students go wrong is when their projects are too descriptive or lack criticality. The same principles apply when using real-world case studies. In-class cases allow students to explore changes in practice, such as new product lines or production techniques. Again, there are formative assessment opportunities in asking students to present their reflections on these developments. Additionally, in exams students can be presented with such examples and asked to reflect on them. It would also be possible to make some element of the exam open-book assessment, in which students draw on work they have done in class to address either cases they have been working on, or cases new to them. Another option might be to provide a case study to be studied in advance of the examination, with the questions unseen until the exam. In this way, depth of understanding, knowledge and analysis is encouraged.

As already hinted at, available software resources also offer opportunities for formative and summative assessment, as well as means of engaging students with core material. Box 6 discusses a range of these, and boxes 3 and 10 consider software on valuation and life cycle assessment respectively.

↑ Top7. Case studies

- "The COP Negotiation Game." Alexandra Arntsen, Nottingham Business School, Nottingham Trent University

- "Sustainable communities and HE: the 3Cs approach to co-creation and sustainability education." Lory Barile, University of Warwick

- "Discussing climate change via the history of economic thought." Andrew Mearman, University of Leeds

8. Readings

Works cited in the text

Ackerman, F. (2009). "The New Climate Economics: The Stern Review versus its critics", in J. Harris and N. Goodwin (Eds.) Twenty First Century Macroeconomics: Responding to the Climate Challenge, Cheltenham: Elgar.

Advance HE/QAA (2021). Education for Sustainable Development Guidance. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/education-sustainable-development-guidance

Almansa, C., & Martínez-Paz, J. M. (2011). Intergenerational equity and dual discounting. Environment and Development Economics, 16 (6), 685-707. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X11000258

Barile, L. (2022). "Can we be nudged to act on climate change?" Warwick Business School. Available at: https://www.wbs.ac.uk/news/can-we-be-nudged-to-act-on-climate-change/

Baumgärtner, S. and Quaas, M., (2010). What is sustainability economics? Ecological Economics, 69 (3), pp.445-450. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1469961

Bayliss, K. and Fine, B. (2020). A guide to the systems of provision approach, Routledge.

Becker, C. (2006). "The human actor in ecological economics: philosophical approach and research perspectives", Ecological Economics, 60 (1): 17–23. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.12.016

Bradley, P., Parry, G. and O’Regan, N., 2020. "A framework to explore the functioning and sustainability of business models." Sustainable Production and Consumption, 21, pp.57-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2019.10.007

Colander, D., Howitt, P., Kirman, A., Leijonhufvud, A. and Mehrling, P. (2008). ‘Beyond DSGE Models: Towards an Empirically-Based Macroeconomics’, paper presented at the AEA meetings, 2008. http://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.236

Cook, I., 2020, Future graduate Skills: A scoping Study. EAUC Report. Available at: https://www.sustainabilityexchange.ac.uk/files/future_graduate_skills_report_change_agents_uk_eauc_october_2020.pdf

Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. Paruelo, J., Raskin, R., Sutton, P. and van den Belt, M. (1991). "The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital", Nature, 387: 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

Council of the European Union (2010). Council Conclusions on Education for Sustainable Development, Brussels.

Dasgupta, P. (2007). "Comments on the Stern Review’s Economics of Climate Change", National Institute Economic Review, 199, London: Sage. http://doi.org/10.1177/002795010719900102

Dasgupta, P. (2021). The economics of biodiversity: the Dasgupta review, HM Treasury.

The Economist (9 September 2010). "Invisible Carbon Pumps"

European Commission (2022) Proposal for a Council Recommendation on learning for environmental sustainability. COM (2022) 11 final. Brussels, 14.1.2022

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, Oxford, Capstone.

Forsyth, F. (2010). "Problem-based learning" in The Handbook for Economics Lecturers, Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n1164a

Georgescu-Roegen, N., (1986). "The entropy law and the economic process in retrospect." Eastern Economic Journal, 12 (1), pp. 3-25. JSTOR: 40357380

Goodin, R. (1982). Discounting Discounting. Journal of Public Policy, 2 (1), pp. 53-71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00001793

Goodwin, N. (2003). "Five Kinds of Capital: Useful Concepts for Sustainable Development", Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University, Medford MA 02155, USA, Working paper no. 03-07

Green, T.L., (2013). Teaching (un) sustainability? University sustainability commitments and student experiences of introductory economics. Ecological Economics, 94, pp.135-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.08.003

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., ... & van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5 (12), e863-e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Hoggett, P. (Ed.). (2019). Climate psychology: On indifference to disaster. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kioupi, V., & Voulvoulis, N. (2022). The Contribution of Higher Education to Sustainability: The Development and Assessment of Sustainability Competences in a University Case Study. Education Sciences, 12 (6) 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060406

Kula, E., & Evans, D. (2011). Dual discounting in cost-benefit analysis for environmental impacts. Environmental impact assessment review, 31 (3) pp. 180-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2010.06.001

Luo, Y. and Zhao, J., (2021). Attentional and perceptual biases of climate change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42, pp. 22-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.010

Lynas, M., Houlton, B. Z., & Perry, S. (2021). Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters, 16 (11), 114005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966

Malesios, Chrisovalantis & De, Debashree & Moursellas, Andreas & Dey, Prasanta & Evangelinos, Konstantinos. (2020). "Sustainability Performance Analysis of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises: Criteria, Methods and Framework." Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100993

Marshall, G. (2015). Don't even think about it: Why our brains are wired to ignore climate change. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Martinez-Alier, J., (2013). Social metabolism, ecological distribution conflicts and languages of valuation. In Beyond Reductionism (pp. 35-61). Routledge.

Mattioli, G., Roberts, C., Steinberger, J.K. and Brown, A., (2020). The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach. Energy Research & Social Science, 66, p.101486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486

Meadows, D., Meadows, D., Randers, J. and Behrens, W. (1972). The Limits to Growth, New York: Universe Books.

Mearman, A. (2017). "Teaching Heterodox Economics and Pluralism", The Handbook for Economics Lecturers, Bristol: The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n2923a

Murray, P. (2011). The Sustainable Self, Oxford: Earthscan.

Nordhaus, W. (2007). "The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change", Journal of Economic Literature, 45 (3): 686–702. JSTOR 27646843

Oreskes, N., and Conway, E. M. (2012) Merchants of Doubt, London: Bloomsbury

Paine, R. (1969). "A note on Trophic Complexity and Community Stability", The American Naturalist, 103 (929): 91–93. JSTOR 2459472

Pelenc, J. (2015). "Weak versus Strong Sustainability" (Technical briefing) https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3265.2009

Perman, R., Ma, Y., McGilvray, J. and Common, M. (2003). Natural Resource and Environmental Economics, Harlow: Pearson.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (2023). Subject Benchmark Statement: Economics

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F.S., Lambin, E., Lenton, T.M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H.J. and Nykvist, B., (2009). "Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity." Ecology and society, 14 (2). JSTOR 26268316

Scott Cato, M. (2008). Green Economics: An introduction to theory, policy and practice, London: Earthscan.

Stern, N. (2006). The Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change, London: HM Treasury.

UNESCO (2020). Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2020. https://doi.org/10.54675/YFRE1448

Victor, P. (2008). Managing without Growth: Slower by design, not disaster, Cheltenham: Elgar.

Victor, P. and Rosenbluth, G. (2007). ‘Managing without growth’, Ecological Economics, 61: 492–504. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.03.022

Wheatley, D. (2011) "Developing a web-based teaching and learning resource for cost benefit analysis: CBA Builder", The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n1299a

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the Brundtland Commission, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Witham, H. and Mearman, A. (2008). "Problem-Based Learning and Ecological Economics", The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n595a

Xie, B., Brewer, M. B., Hayes, B. K., McDonald, R. I., & Newell, B. R. (2019). Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 65, 101331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101331

Other works cited in linked boxes (listed by box)

Box 1

Turner, A. (2020). Techno-optimism, behaviour change and planetary boundaries. Keele World Affairs Lectures on Sustainability, available at http://www.kwaku.org.uk/Documents/Techno%20optimism%20behaviour%20change%20and%20planetary%20boundaries%20Nov%202020.pdf

Box 4

Dafermos, Y., Nikolaidi, M. and Galanis, G. (2017) A stock-flow-fund ecological macroeconomic model, Ecological Economics, 131: 191-207, ISSN 0921-8009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.013.

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. and Hultink, E. J., (2017). The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of cleaner production, 143, pp. 757-768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048

Gough, I., (2019). Universal basic services: A theoretical and moral framework. The Political Quarterly, 90 (3), pp. 534-542. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12706

Keen, S. (14 November 2019). "‘4°C of global warming is optimal’ – even Nobel Prize winners are getting things catastrophically wrong" The Conversation

Kahneman D., Knetsch, J. L. and Thaler, R. H. (1990). "Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem" Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98, No. 6, pp. 1325-1348 JSTOR 2937761

Nikiforos, M. and Zezza, G., (2018). Stock‐Flow Consistent macroeconomic models: a survey. Analytical Political Economy, pp. 63-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12221

UN (2022). Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) and Energy-Environment-Economy (E3) models

Box 6

Godley, W. and Lavoie, M., (2006). Monetary economics: an integrated approach to credit, money, income, production and wealth. Springer.

Jackson, T. and Victor, P. A., (2020). The transition to a sustainable prosperity-a stock-flow-consistent ecological macroeconomic model for Canada. Ecological Economics, 177, pp. 1067-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106787

Box 7

Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. Paruelo, J., Raskin, R., Sutton, P. and van den Belt, M. (1991). ‘The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital’, Nature, 387: 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

Daly, H. E., (1991). Elements of environmental macroeconomics. in Costanza, R. (Ed.) Ecological economics: The science and management of sustainability, Columbia University Press. pp. 32-46.

Box 9

Copestake, J. and Ellum, T. (2010). "The Global Climate Change Game" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n1143a

Guest, J. (2007). "Introducing Classroom Experiments into an Introductory Microeconomics Module" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n191a

Hedges, M. R. (2004). "Tennis Balls in Economics" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n146a

International Energy Agency (2021). Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. Paris: IEA.

McDonough, W. and Braungart, M. (2002). Cradle to Cradle: Rethinking the way we make things, San Francisco: North Point Press.

Piggott, J. (2003). "Follow up to 'Students' assignment as a piece of economics journalism'" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n580a

Sloman, J. (2002). "The International Trade Game" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n141a

Sloman. J. (2009). "Deal or No Deal – an expected value game" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n939a

Sutcliffe, M. (2002). "The Press Briefing Role-Play" The Economics Network https://doi.org/10.53593/n210a

Box 10

Shaik Khaja Mohidin, A., Wong, M. L. D., and Choo, C. M. (2018) "Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of a Standalone Hybrid Energy Storage System for Rural Electrification" (preprint)

Books

These books are economics textbooks. They would be suitable at levels 2 and upwards, although for each book, clearly students at level 2 would need more help in understanding the material presented.

Common, M. and Stagl, S. (2005). Ecological Economics: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Costanza, R. (1992). Ecological Economics: the Science and Management of Sustainability, New York: Columbia University Press.

Daly, H. and Farley, J. (2004). Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications, Washington, DC: Island Press (and workbook).

Harris, J. and Goodwin, N. (Eds.) (2009). 21st century macroeconomics: responding to the climate challenge, Cheltenham: Elgar.

Scott Cato, M. (2008). Green Economics: An introduction to theory, policy and practice, London: Earthscan.

Soderbaum, P. (2008). Understanding sustainability economics: towards pluralism in economics, London: Earthscan.

Spash, C. L. (Ed.) (2009). Ecological economics: Critical concepts in the environment, Vols. 1–4, London: Routledge.

These readings are intended as companion texts; they are not textbooks. They deal with sustainability issues such as energy, change management strategy, and personal consumption decisions. They are suitable at many levels, although some of the technical detail is more suitable for higher level students.

Fanning, A. L., O’Neill, D. W., Hickel, J., Roux, N. (2021). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nature Sustainability, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00799-z

Hardin, G. (1968). "The tragedy of the commons." Science, 162, 1243-1248. JSTOR 1724745

Murray, P. (2011). The Sustainable Self, Oxford: Earthscan.