Facilitators' handbook for a PBL module in Macroeconomic Analysis and Policy

Kennedy Okparaolu, Abdulla Shaheed, Dr Yaprak Tavman and Dr Ning Xue

University of York

Published November 2024

Contents

- Introduction to the handbook

- Aims of the handbook

- The Macroeconomic Analysis and Policy course

- Changes to the Teaching and Learning Environment

- Introduction to Problem-based Learning

- Preparation for Teaching and Learning with PBL

- The PBL Process

- Roles and Responsibilities of the Team Members and Facilitator

- Bibliography

Dr Tavman and Kennedy Okparaolu, Abdulla Shaheed, and Dr Ning Xue (listed in alphabetical order) have developed a facilitators' handbook to demonstrate the implementation of Problem-Based Learning in an intermediate macroeconomics module in 2024-25. This page is adapted from that handbook.

↑ TopIntroduction to the handbook

This handbook provides essential information to facilitators about adopting problem-based learning (PBL) for the module Macroeconomic Analysis and Policy. The handbook has been designed incorporating feedback from Economics students which has been critical for developing a positive PBL experience. Therefore, it is essential for facilitators to engage with it. There is a separate PBL handbook for students and students should be encouraged and reminded throughout the semester to refer to it.

↑ TopAims of the handbook

This handbook aims to provide facilitators an overview of PBL, with a focus on teamwork and collaboration. Ultimately, PBL should provide an enhancement of students’ learning and employability skills. This can be achieved through a deeper understanding of complex economic situations (i.e. PBL tasks) and responding to these working in teams. The handbook contains guidance to be used throughout the module to support the learning and teaching experience of students, as they collaborate to solve PBL tasks innovatively. We hope students participate enthusiastically throughout the sessions, which will help them develop the skills highly demanded by employers.

The Macroeconomic Analysis and Policy course

Module summary

This module advances students’ understanding of macroeconomic models, analysis and policy. It involves problem-based learning (PBL), a student-centred approach where students, in small groups, work collectively to tackle a variety of macroeconomic problems.

Learning outcomes

On completing the module, students will be able to

- Understand and use a set of macroeconomic models to analyse macroeconomic issues in the short run, medium run and the long run, such as macroeconomic stabilisation, inflation, unemployment and economic growth.

- Critically assess the use of macroeconomic policies, specifically monetary and fiscal policy.

- Demonstrate a positive contribution to their and their peers’ learning, by regular attendance and participation in PBL seminars.

- Plan basic research strategies to identify, evaluate and apply macroeconomic theories and policies to a broad range of macroeconomic issues.

- Apply and adapt basic problem-solving skills to address new problems.

- Demonstrate clarity and precision in verbal and written communication.

- Develop skills to work independently and as part of a group, drawing upon personal and interpersonal skills established as part of problem-based learning.

- Reflect critically on individual and peer contributions to teamwork and on their own development.

Assessment

Formative

Students will be given 3 PBL tasks.

- Written team response for Tasks 1-3 (1000 words max. per task)

- Feedback will be provided by facilitators within one week of submission.

The 3rd PBL task has been set jointly by members of the HM Treasury Macroeconomic Policy Group.

- Team presentation for Task 3 (25 mins) in Week 10 seminar.

- Top 5 teams chosen by facilitators will also have the opportunity to present their answer to members of the HM Treasury Macroeconomic Policy Group in the last lecture in Week 11, on Friday December 13th at 1 pm.

Summative

- 2-hour in-person exam - 75%

- Coursework (2500 words max) - 25%

- Part A (1500 words max): PBL task response

- Students will choose one of the 3 PBL formative tasks and write their individual response to it after incorporating the feedback they had received for their team response.

- Part B (1000 words max): Reflection

- Students will be given questions to reflect on their experience with PBL when they were working on their formative answer to the chosen task.

- Part A (1500 words max): PBL task response

Changes to the Teaching and Learning Environment

Even though the traditional lecture style of teaching remains impactful, institutions observe the academic process continually and strive to improve student outcomes, as universities’ teaching objectives continue to change (Schwerdt & Wuppermann, 2009). This continuous review attempts to match an answer to one of the most extended outstanding curriculum questions of "what is worth learning" with the current real-world expectations of students (Anderson et al., 2001). The traditional teaching approach usually emphasises the lecturers' direction and the students' attention. However, more is needed to sufficiently develop valued skills for students, which goes beyond retaining knowledge for exams (Tularam & Machisella, 2018).

Training students to acquire adequate and relevant skills to improve their prospects of competing and thriving after graduation is becoming increasingly important for the functioning of universities (McCowan, 2015). For this purpose, developing a learning environment that serves to increase students' level of participation in group learning to work towards achieving a common goal can be vital. Such a learning environment can be facilitated through problem-based learning. According to Myers & Botti (1998), this learning approach also provides an inquiry-based environment where students use critical and logical thinking to approach complex situations. In addition to providing alternative explanations through asking questions, students describe events or scenarios, test each other’s explanations, and communicate their ideas within their group.

PBL requires the facilitator's adoption of facilitative teaching skills during group sessions to hone independent and self-directed learning and develop students’ reasoning skills (Barrows, 1992). Therefore, in contrast to traditional teaching, PBL guides group participation towards individual and group inquiry into what we know, what evidence supports that knowledge, which arguments interpret the evidence and of similar importance, what alternative explanations or approaches will offer a more efficient method of solving the problem (Myers & Botti, 1998).

↑ TopIntroduction to Problem-based Learning

Definition and History of PBL

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centred approach that focuses on students and their exploration of real-world problems. Students undertake teamwork in conjunction with self-directed learning to tackle a number of tasks which are often based on real-world scenarios. It places the students at the centre of the learning process in a manner unlike or in distinction from the lecture-based format frequently characterised as a standard way of information transmission from the instructors to the students.

Problem-based learning was developed in the mid-20th century in North American medical education, mainly through the work of Dr Howard Barrows, who aimed to redirect students from rote memorisation towards practical clinical problem-solving skills. The approach was designed to better prepare medical students for real-life clinical scenarios by enhancing their critical thinking ability and applying knowledge in practical settings (Marra et al., 2014). Since then, it has expanded to many other disciplines, including law, economics and engineering.

Benefits of PBL

PBL offers several benefits including a deeper approach to learning (Gibbs, 1992). Students have the opportunity to engage with real-world problems, retain, recall and apply what they learn in their lectures, and enhance their understanding beyond lecture materials and readings. Responding as a team to a practical economic issue faced in the real world improves students’ motivation by making learning a collaborative and enjoyable experience.

This method of learning also helps students with developing soft skills that are expected from university graduates, such as leadership, teamworking and time management. These skills can be useful in the extremely competitive job market, particularly in economic roles in the public and private sectors. Additionally, it helps students enhance their research skills, which are extremely important for roles in think tanks, research institutions and policy advisory positions. For example, collaborating, leading, communicating, and making effective decisions, which are all enhanced through PBL, are some of the skills highlighted in the UK Civil Service Competency Framework.

Additionally, since the learning in the PBL environment is group-based, student interaction sustains an essential exchange between diverse groups, which satisfies the critical cohesion requirement for current learning standards. For example, poor engagement is determined to be responsible for the underachievement of certain ethnic groups (see Bingham & Okagaki, 2012).

↑ TopPreparation for Teaching and Learning with PBL

Following the change from a teacher-centred to a student-centred teaching and learning environment, it is inevitable that new opportunities and challenges will emerge. This handbook prepares facilitators for the new teaching format and guides them through learning and teaching with PBL.

The Learning Process and Environment in a Student-centred Approach

Students’ Approach to Learning

The approach to learning in PBL emphasises the depth of students’ understanding, individually and collectively (see Biggs and Tang, 2007). The group framework at the forefront of the PBL experience emphasises active group activity's impact on efficient learning outcomes. It observes students’ general ability to construct and co-construct ideas via self-directed learning and social interactions (Yew & Goh, 2016). Moreover, approaching tasks with deep cognitive activities appropriately and meaningfully contributes to a positive feeling of interest, a sense of importance, feeling challenged and, in some cases, exhilaration (Steenhuis & Rowland, 2018).

Therefore, the PBL environment encourages students to connect - individually and as a group - with the learning activity by activating their prior knowledge, which will help them understand and make sense of the presented challenging PBL tasks. Ultimately, students will engage in meaningful learning and develop an understanding of themselves and their learning patterns, while being properly guided towards enhancing their abilities. Table 1, adapted from Anderson et al. (2001), illustrates three scenarios to explain how students' approach to learning can impact the resulting learning process and highlights the strengths of meaningful learning.

Table 1 Three Learning Outcomes

| No Learning | Rote learning | Meaningful learning |

|---|---|---|

Student A reads a chapter on electrical circuits in her science textbook. She skims the material, sure that the test will be a breeze. She can remember very few key terms and facts when asked to recall part of the lesson. For example, she cannot list the major components of an electrical circuit, even though they were described in the chapter. She cannot produce an answer when asked to use the information to solve problems (as part of a transfer test). For example, she cannot answer an essay question asking her to diagnose an electrical circuit problem. In this worst-case scenario, student A has neither sufficiently attended to nor encoded the material during learning. The resulting outcome is essentially no learning. | Student B reads the same chapter on electrical circuits. She reads carefully, making sure she reads every word. She goes over the material and memorises the key facts. When asked to recall the material, she can remember almost all of the important terms and facts in the lesson. Unlike student A, she can list the major components of an electrical circuit. However, she cannot produce an answer when asked to use the information to solve problems. Like student A, she cannot answer the essay question about diagnosing a problem in an electrical circuit. In this scenario, student B possesses relevant knowledge but cannot use that knowledge to solve problems. She cannot transfer this knowledge to a new situation. Student B has attended to relevant information but has not understood it and cannot use it. The resulting learning outcome can be called rote learning. | Student C reads the same chapter on electrical circuits in the textbook. She reads carefully, trying to make sense out of it. When asked to recall the material, she, like student B, can remember almost all of the important terms and facts in the lesson. Furthermore, she generates many possible solutions when asked to use the information to solve problems. In this scenario, student C not only possesses relevant knowledge but can also use that knowledge to solve problems and understand new concepts. She can transfer her knowledge to new problems and new learning situations. Student C has attended to relevant information and understood it. The resulting learning outcome can be called meaningful learning. |

Facilitators’ Approach to Teaching

Reviews of both the teacher-centred and student-centred models indicate that a change in paradigm is essential to prepare students adequately for life after graduation. As discussed in Steenhuis & Rowland (2018), in recognition of the limited progress students make on developing skills such as critical thinking, analytical reasoning and problem-solving and the attainment of set learning objectives in higher education, institutions should incorporate teaching methods which place the student at the centre of the learning experience.

The change to PBL aims to transfer from the more traditional teacher-centred approach, where the teacher functions as the lecturer, passing knowledge to passive students, to a more student-centred approach, where the teacher functions more as a coach or facilitator, to guide students towards an active and collaborative role in their learning process (Lathan, 2024).

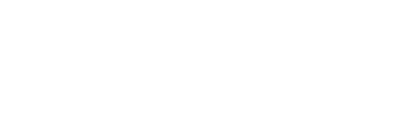

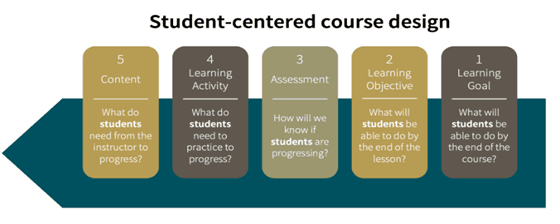

Figure 1 Student-centred vs. teacher centred course design

(Source: Stanford University, 2023)

Figure 1 provides a comparison of the two approaches. In this module, a "student-centred approach" considers the class environment to be "a learning community that constructs shared understanding" (Brophy, 1999, p. 49).

Although the distinctions between the teacher- and student-centred course design concern the learning content and activities, educational goals, assessment criteria and procedures, the facilitator's disposition to the educational, mentoring and motivational responsibilities are all impacted (Steenhuis & Rowland, 2018). How this translates into practical differences in learning environments is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Teacher-centred vs. Student-centred Learning Environment

| Teacher-Centred Learning Environment | Student-Centred Learning Environment |

|---|---|

|

|

(Source: Adapted from Lathan, 2024)

Facilitators may recognise that the learning process and environment ultimately affects the individual level of performance with the learning content, outcomes, and objectives. Table 3 provides a guide for facilitators' corresponding approaches to learning outcomes, knowledge acquisition and use, and skills development in teaching-centred and learning-centred environments.

Table 3 Teaching-centred vs. Learning-centred orientations

| Dimensions | Desired learning outcomes | Expected use of knowledge | Responsibility for organising or transforming knowledge | Nature of knowledge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching-centred orientation | Imparting information | Recall of atomised information | Within subject | Teacher | Externally constructed |

| Transmitting structured knowledge | Reproductive understanding | Within subject for future use | Teacher | Externally constructed | |

| Providing and facilitating understanding | Reproductive understanding | Within subject for future use | Teacher shows how knowledge should be used | Externally constructed | |

| Learning-centred orientation | Helping students develop expertise | Change in ways of thinking | Interpretation of reality | Student and Teacher | Personalised |

| Preventing misunderstanding | Change in ways of thinking | Interpretation of reality | Students | Personalised | |

| Negotiating understanding | Change in ways of thinking | Interpretation of reality | Students | Personalised | |

| Encouraging knowledge creation | Change in ways of thinking | Interpretation of reality | Students | Personalised | |

(Source: Steenhuis & Rowland, 2018)

↑ TopThe PBL Process

PBL involves working in teams, where students brainstorm the knowledge that they must acquire to handle a problem. This is done after discussing various aspects of the problem in the team and is concluded with an identification of learning goals. After that, the team and the individual take it upon themselves to learn about the areas they think they must know, and they meet again to share and discuss their findings. This brings you to the other side of the process: the facilitator, who certainly takes a role in facilitation rather than engaging in a more traditional way of teaching. As the facilitator, you will ensure that the discussion continues, that the team is on the right path, and that learning goals are met.

PBL promotes utilisation of theory in practical scenarios via:

- Teamwork: In PBL, students will solve a complex problem in macroeconomics by cooperating with their team members. For example, it may be the team's task to analyse the relationship between unemployment and inflation by evaluating the Phillips curve. Students may study historical evidence from various countries and make recommendations based on their findings.

- Self-Directed Learning: Students take the initiative to figure out the key knowledge gaps and close them.

- Real-world Problems: PBL significantly makes use of real-world problems. For example, what could be the economic implications of Brexit for the UK economy? There have been many discussions about its impact in Parliament and around the country, but what do the macroeconomic models show?

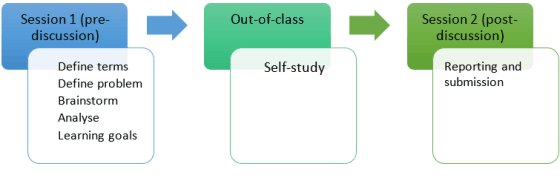

The PBL Cycle

Please make sure students bring laptops/tablets to their seminars, as they will need to write down their work in collaborative documents as a team.

Seminar 1

In this seminar students will be introduced to PBL and their teams. There are 2 teams in each seminar group. Before the seminar starts, facilitators should prepare and identify a table for each team in the seminar room.

- When students come to the first seminar, facilitators should ensure that students sit around the table for their team (Ask students their names and let them know which team they are in if they are not sure or provide them a list).

- First, facilitators will introduce themselves: Name, position, background, research interest, hobbies etc and present an introduction to PBL. (20 mins)

- Second, students will be given time to get to know each other using the name game or any other icebreaker activity. After this activity, encourage the students to make nameplates for themselves. (10 mins)

- Students will then be asked to open their team’s Google Drive folder and the interactive learning document (ILD) located in there.

- Whilst engaging with the PBL tasks, creating an inclusive and respectful learning environment for all is essential. Students should be asked to create a bullet-point list detailing the etiquette that they will follow during the module and one student should volunteer as scribe to type the list in the ILD. (20 mins)

- This should include:

- Terms of Engagement: How will students collaborate and interact? Which communication platforms will they utilise? What steps should be taken if a team member is unable to attend a seminar?

- Expectations: What do students anticipate from one another regarding attendance, punctuality, work quality, and communication? Are there any additional expectations?

- Each team member should type their name under the list to signify their commitment.

Seminars 2-7

Each task consists of 2 seminars (pre-discussion and post-discussion) and students will need to complete 3 tasks from Seminar 2 to Seminar 7 using the 7-step approach (details of which are provided on pages 14-15).

Students should document all the steps of the 7-step approach for each task and have their team’s written response (1,000 words max.) ready at the end of each post-discussion session in their ILD.

Facilitators can use the same document to provide their written feedback for each task within one week of submission. Feedback should:

- Focus on 4-5 actionable points for improvement.

- Be specific.

From time to time, facilitators should also spare 5 minutes at the end of the session to provide constructive verbal feedback. You could then ask the teams how they thought the session went and identify what you saw as the problematic issues if there were any.

Detailed facilitators’ notes are provided for each task separately. Facilitators should make sure to read these before the start of the pre-discussion session for each task.

Seminar 8

The final PBL task has been set jointly by members of the HM Treasury Macroeconomic Policy Group. In addition to providing a written answer, students will also be required to present their answer to this task as a team in the Week 10 Seminar.

Each team will give a 25-minute presentation (15 minutes for the team to present and 10 minutes for Q&A).

Facilitators will ask questions at the end of the presentation and will provide verbal feedback to the team. They should also assign a mark to each presentation using the mark breakdown in the presentation marksheet.

Top 5 teams chosen by the facilitators will also have the opportunity to present their answer to members of the HM Treasury Macroeconomic Policy Group in the Week 11 lecture.

Please see the formative presentation assessment brief and marking criteria on the module VLE for further details.

The 7-step approach in PBL

This is the seven-step approach all teams are expected to follow when responding to PBL tasks. In each task, every team will have a Chair, a Scribe and a Task Manager with these roles being rotated (See below for details of each role).

1. Defining Unknown Terms

The problem might contain vague terms and concepts. These need to be looked up and/or explained so that each member of the team is on the same level regarding information provided. Terminologies such as "inflation rate", "consumer price index (CPI)," and "purchasing power" might be unfamiliar to some students. When all team members understand the definition and usage of these terms, it is time to progress to the next step.

2. Defining the Problem

The problem could be defined as a single question or multiple questions. The team must agree on the phenomena that need to be explained. For example, one might ask “How does inflation impact government or central bank policies?”. When a clear problem is identified and a question or questions have been formed, this step is finished. There is also a chance that in the seminar session, the questions might already be presented to students or provided to them in the question set. In that case, students will be spending less time on forming questions or identifying the problems.

3. Brainstorm

This is the more interesting step, where everyone starts brainstorming and a lot of knowledge sharing is done. Different team members might be coming from different educational backgrounds or might have studied slightly different modules in the past. They could all offer as much insight, theories, and hypotheses as possible. For example, some members might argue that high inflation could force the government to reprioritise their spending plans to reduce demand in the economy. Other members might argue that it might not be the best approach if inflation was caused by supply side factors and that the government might need to implement supply side policies such as reducing regulatory burdens and increasing productivity. When the team is satisfied with the number of ideas and explanations they have generated, they are ready to move on.

4. Analysing the Problem

All the thoughts, ideas and explanations from the previous step are transferred here. Then a systematic analysis is done by evaluating each and every idea. In the previous step, students were simply offering ideas and hypotheses. Detailed discussions are carried out in this step. For example, in depth discussions such as whether inflation is caused by demand side or supply side policies will be made. How it can potentially be tackled will also be thoroughly discussed in this stage. Step four is complete when all of the key points from step three have been considered in detailed discussions and summarised into key themes.

5. Formulating Learning Goals

By now, there will be concepts and theories that students are familiar with or already know. Then there will also be some areas where students feel are possibly relevant to providing an adequate response to the question in hand, but they need to do additional research. This is what we call a learning goal. So, in this step the team members can list down everything they need to research, study and learn before the next meeting again. For example, this could be related to the transmission mechanism of the monetary policy. Students might know that interest rates are used to influence inflation, but they might not be aware of how exactly it affects inflation. This information will be available in the literature. Once the team has listed down all the learning goals, assigned research tasks to different members of the team to achieve these learning goals, and once everyone has agreed on that, students can move to step six.

6. Self-study

Before this step, students might have done a bit of research in the classroom on their laptops. But most of the research is expected to be done outside classroom hours. Here, students will do an in-depth literature review and study all relevant materials. Each member could be assigned a task or a specific paper to read or research. For example, one member might be tasked with reviewing Bank of England’s research reports, the other member with case studies, another with reviewing lecture notes and/or textbooks. It is very important to document all the analysis and findings in the team’s shared document. Next is the final step.

7. Reporting

After a week, students will all meet again to discuss their findings. It is likely that different team members have come up with different conclusions during this self-study period. The team must discuss the findings thoroughly and form a comprehensive understanding of the topic. The findings should be related to the learning goals set out in step five. Students should prepare a written answer and submit it to the facilitator at the end of this session. However, if tasks remain, students should agree on task allocation and deadlines to ensure the work is completed on time.

The PBL Cycle Flow

| Seminar 1 |

| Seminars 2 to 7 |

This process will repeat for each of the three tasks from seminar 2 through seminar 7 as below.

| Seminar | Task, Session |

|---|---|

| Seminar 2 | Task 1, Session 1 |

| Seminar 3 | Task 1, Session 2 |

| Seminar 4 | Task 2, Session 1 |

| Seminar 5 | Task 2, Session 2 |

| Seminar 6 | Task 3, Session 1 |

| Seminar 7 | Task 3, Session 2 |

| Seminar 8 |

Timetable

| Week | Lecture + Practical | Seminar (one hour) | PBL Tasks | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (w/c 23 Sep 2024) | 3 hours | 2 hours on Thursday 1 hour on Friday | ||

| 2 (w/c 30 Sep 2024) | 2-hour lecture 1-hour Careers session | Careers session: Developing Skills for Collaboration and Future Careers | ||

| 3 (w/c 7 Oct 2024) | 3 hours | Introduction to PBL | ||

| 4 (w/c 14 Oct 2024) | 3 hours | pre-discussion | Task 1 | |

| 5 (w/c 21 Oct 2024) | 3 hours | post-discussion | Task 1 | Submit team answer to Task 1 |

| Consolidation week | ||||

| 6 (w/c 4 Nov 2024) | 3 hours | pre-discussion | Task 2 | Task 1 feedback from facilitator |

| 7 (w/c 11 Nov 2024) | 3 hours | post-discussion | Task 2 | Submit team answer to Task 2 |

| 8 (w/c 18 Nov 2024) | 3 hours | pre-discussion | Task 3 | Task 2 feedback from facilitator |

| 9 (w/c 25 Nov 2024) | 3 hours | post-discussion | Task 3 | Submit team answer to Task 3 |

| 10 (w/c 2 Dec 2024) | 2-hour lecture 1-hour Careers session | group presentations | Task 3 | Task 3 feedback from facilitator Careers session: Importance of Reflection |

| 11 (w/c 9 Dec 2024) | 2-hour revision lecture 1-hour presentations | Top 5 teams chosen by the facilitators present their task 3 response to HM Treasury |

Roles and Responsibilities of the Team Members and Facilitator

Each team must have a chair leading the discussion, a scribe keeping record of the meetings and a task manager monitoring the progress. To get the most out of the process, team members will rotate around these roles.

The rotation of the roles is provided in each team’s ILD. Please make sure to add the names and email addresses of each student for the teams in your seminar groups.

Chair

The chairperson is responsible for the proper structuring of any meetings. This means they set the agenda, observe the relevance of the discussions and ensure that all topics on the agenda are covered. They should encourage all team members to participate in discussions and should not dominate the discussion themselves. The chair also guides the team to work through the seven-step approach, keeps the team focused on the process each step involves and decides when to move on from each step. For example, if the team is tasked with analysing the relationship between unemployment and inflation using the Phillips Curve, then it is their responsibility to set the agenda in such a way that it covers every aspect of the discussion step by step in the seven-step approach. In the post-discussion, the Chair should ensure everyone’s contributions are heard and the group relates their findings to one or more of the learning goals.

Notes for Chair for the 7-step approach

Setup:

The Chair reminds the group the roles they will undertake in each session based on their allocation (Chair, Scribe, and Task manager). The following actions should then be undertaken by the chair:

Step 1: Defining unknown terms

- invites group members to read the task questions and then encourages them to identify and discuss the terms/definitions they find unclear or unfamiliar.

- checks if all group members understand the definitions and terms. If terms remain unclear, then they should be recorded as a learning outcome.

Step 2: Defining the problem

- invites group members to discuss the definitions of the problem. The problem can be defined as a single question or multiple questions.

- checks if all group members agree on the definitions of the problem.

Step 3: Brainstorm

- encourages everyone to contribute and share their knowledge.

- makes sure that everyone’s voices are heard.

- summarises the ideas and makes sure everyone is satisfied to move on to the next step.

Step 4: Analysing the Problem

- invites group members to evaluate each idea discussed in Step 3 and makes sure each idea is thoroughly discussed.

- encourages group members to consider the relationships between ideas.

- summarises the key themes and makes sure the group has a clear schema for how they fit together.

Step 5: Formulating Learning Goals

- encourages group members to discuss the concepts and theories they are familiar with and the areas they want to explore more.

- makes sure that all the areas identified are converted to learning goals and everyone is satisfied.

- allocates responsibility for “research tasks” and makes sure that everyone understands what they need to research and learn. It is via research tasks undertaken that the team can realise the learning goals identified above and provide a final, agreed response to the set task.

Step 6: Self-study

Independent self-study: no action.

Step 7: Reporting

- repeats the learning goals and the tasks assigned to each member in pre-discussion.

- invites each group member to share their findings and relates the findings to each learning goal.

- makes sure that the findings are discussed thoroughly, and the team forms a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

- summarises the findings and concludes each learning goal with a summary.

- checks if all unknown definitions and terms, and learning goals identified in pre-discussion have been addressed.

- makes sure the team agrees on their task response.

Scribe

The scribe does not have to write everything but should summarise key or important contributions that various team members make while discussions are in progress. In other words, the scribe should write down unfamiliar terms, summarise contributions from brainstorming, and indicate relationships between key ideas. The scribe also writes down the Learning Goals. This ensures that vital points regarding the tasks are accurately captured. The scribe uses the interactive learning document (ILD) in their team’s Google Drive folder for this purpose. In the post-discussion, the scribe should write brief, clear summaries of contributions.

Notes for Scribe for the 7-step approach

The following actions should be undertaken by the scribe:

Step 1: Defining unknown terms

- documents all the unfamiliar definitions and terms discussed.

Step 2: Defining the problem

- documents the problem definition, where the problem can be defined as one or more questions.

Step 3: Brainstorm

- documents all the ideas discussed.

Step 4: Analysing the Problem

- documents the key themes that emerged from the discussion of the main ideas from the brainstorm.

Step 5 Formulating Learning Goals

- documents all learning goals.

Step 6 Self-study

- Independent self-study: no action.

Step 7: Reporting

- ensures that the additional points discussed are included in the ILD.

Task Manager

The task manager ensures that each team member's assigned tasks are noted in the ILD, and that everyone stays on schedule to meet deadlines. They make sure all group members record their findings on the ILD before post-discussion and check if the document is clear and easy to read. They are also responsible for compiling and submitting the task responses to the facilitator on time. If there is anything that needs to be asked from the facilitator or communicated to the facilitator, then the task manager must do it in a timely manner.

Notes for Task Manager for the 7-step approach

Setup:

The task manager reminds students to open the interactive learning document where they collaborate. The following actions should then be undertaken by the task manager:

Step 5: Formulating Learning Goals

- documents the allocation of research tasks to meet learning goals and emphasises that members must report back their research results to the group.

Step 6: Self-study

- makes sure all group members upload their findings before post-discussion and checks if the Google document is clear and easy to read.

Step 7: Reporting

- takes a lead in preparing a written answer and makes sure to submit it to the facilitator at the end of post-discussion.

The Facilitator

The facilitator should neither lead the work nor be a source of validation in the room. Instead, they should be an active observer who intervenes when necessary. The facilitator will make sure that students read the task and the aims of the task at the beginning of the session. They should also provide guidance to the teams and ensure that the teams do not move off track; this is considered a necessary intervention. They may ask questions to stimulate the discussion, but mostly this should come from other team members. They must also give feedback on each team’s work, outlining actionable points with reasons.

Preparation

- Facilitators must review each task and its aims and read the associated facilitators’ notes before the start of the session. They can prepare probing questions that can be useful to stimulate the discussion.

- They must make sure that they are familiar with the PBL framework, and the specific content required for that task. They must go over the suggested answer for the task given in the facilitator notes and familiarise themselves with the databases or models that are provided in the suggested answer. For example, the 3-equation model and the Phillips Curve.

- It is always a good idea to prepare some written notes/materials for each session.

Task presentation

- The facilitator needs to make sure that students read the task and the aims of the task at the beginning of the session.

- Then they must also ensure that students can access the necessary resources, such as key readings and/or datasets.

Guidance and support

- It must be noted that students are supposed to take the lead in discussions and problem solving. However, in the initial sessions, the facilitator may need to take a more active role in guiding the process, serving as a role model for the students.

- Students can often expect the facilitator to provide ‘the answer’ or ask questions directly to the facilitator, particularly if they don’t understand something. These should be referred back to the whole team and students should be reminded that this is not the facilitator’s role.

- Facilitators must only intervene when it is necessary to keep students on track or to provide clarifications on complex issues, using the following strategies:

- Pose open-ended questions to encourage deeper thinking, such as asking how raising the policy rate impacts inflation expectations and unemployment in both the short and long run.

- Prompt students to elaborate on the whats, whys, and hows of their ideas.

- Paraphrase student responses to clarify concepts and identify key points in the discussion.

- Highlight areas where students may have struggled to provide clear definitions or explanations.

Summarize the main ideas you’ve gathered from the discussion to seek students’ confirmation or corrections.

- Pose open-ended questions to encourage deeper thinking, such as asking how raising the policy rate impacts inflation expectations and unemployment in both the short and long run.

- Facilitators must always encourage critical thinking and collaboration to explore different perspectives and solutions to the problems.

- They must be explicit about why they are intervening and give the floor back to the students.

Monitoring and feedback

- Facilitators should check on the teams to ensure that satisfactory progress is made. If students are not getting on with the task you can observe the time and tell students how much time is left, e.g. “Just to remind you, it’s 10:30 now, so you have 20 minutes left to complete learning goals and task allocations.”

- It is also important to observe team dynamics and participation in the discussion. The facilitator must make sure that all students are engaged, are contributing to the discussion and all voices are heard. Ideally, the facilitator should do this by reminding the Chair of their role rather than taking over.

- If a team shows an overall lack of discussion and non-contribution persists, consider inviting students to reflect on their teamwork dynamics and explore ways to improve their engagement in the process. Encouraging them to identify barriers to participation and discuss strategies to overcome these obstacles can be a valuable exercise. If certain voices are dominating the discussion, then facilitators may step in to ensure there is equal input from all students, in other words a more balanced participation. The idea is to provide an inclusive environment that all students feel comfortable contributing to, by supporting and valuing all contributions. Please see the practical tips below on how to approach dominant students.

- Some students might be shy and not talkative. But that does not mean that they lack content or knowledge. When you make them feel comfortable, they are more likely to start talking and making contributions. Please see the practical tips below on how to approach quiet students.

- In addition to the written feedback provided for teams’ responses to the tasks, facilitators can provide constructive verbal feedback at the end of some sessions. You could then ask the teams how they thought the session went, ask them what worked and what didn’t and identify what you saw as the problematic issues if there were any.

Practical tips

Free riding/ lack of attendance

- Ask the others in the team if they know why the student is not attending and check to see whether they are attending other seminars/lectures. You could also arrange for one or two team members to discuss informally with the student and encourage them to attend.

- You could also have a private chat with the student to understand why they are not participating and explain why it is important for them to contribute and how it will affect their career.

- You can also encourage the student to reflect on their behaviour.

- The icebreakers and team building exercises used at the beginning should help with creating a safe, inclusive environment.

Team dynamics

- It is always a good idea to remind students of the ground rules that they had come up with in the first seminar, if there are issues with communication within the team.

- Have eye contact and non-verbal communication, such as gestures to signal issues without interrupting the flow of discussion.

- Provide tips to students for handling different issues if they are not able to find a solution on their own.

- Provide positive reinforcement for contribution.

- For bigger issues, use a personal approach and ask the module coordinator to step in when necessary.

Dominant students

- You can remind the Chair to take greater control if certain students are consistently dominating the conversation.

- You can have a private chat with dominant students, telling them e.g. “You are doing great, but we also want others to participate and not rely too much on you. Can you wait at the beginning a bit for others to contribute?”

Quiet students

- If there are a number of quieter students, it may be useful to raise it in the session and remind students of the ground rules they came up with to make sure that they are including everyone.

- Have a private chat with quiet students to understand what is happening and ask them what would help them.

- Advise them to prepare notes beforehand with 2-3 points and make a plan to make them feel comfortable.

Bibliography

Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R., Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, Richard, Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J. and Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Vol 2. Essex, London: Pearson.

Barrows, H.S. (1992). The Tutorial Process. Springfield, Illinois: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2007). Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 3rd ed. Berkshire, England: Open University Press.

Bingham, G.E. and Okagaki, L. (2012). Ethnicity and Student Engagement, in S.L. Christenson, A.L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (eds.) Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. New York, New York: Springer, 65–95.

Brophy, J.E. (1999). Beyond Behaviorism: Changing the Classroom Management Paradigm. Edited by H.J. Freiberg. Boston, Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon.

Gibbs, G. (1992). Improving the Quality of Student Learning, Technical and Educational Services Ltd, Bristol.

Hmelo-Silver, C., Bridges, S., McKeown, J., Moallem, M., Hung, W. and Dabbagh, N. (2019). The Wiley Handbook of Problem‐Based Learning. 297-319. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119173243.ch13 .

Lathan, J. (2024). Complete Guide to Student-centered vs. Teacher-centered Learning, University of San Diego Online Degrees. Available at: https://onlinedegrees.sandiego.edu/teacher-centered-vs-student-centered-learning/ (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Marra, R., Jonassen, D. H., Palmer, B., and Luft, S. (2014). Why Problem-based Learning Works: Theoretical Foundations. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25 (3 and 4), 221-238.

McCowan, T. (2015). Should universities promote employability? Theory and Research in Education, 13 (3), 267-285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878515598060 .

Myers, R.J. and Botti, J.A. (1998). Exploring the Environment: Problem-Based Learning in Action, cet.edu. Available at: http://www.cet.edu/pdf/ete.pdf (Accessed: 15 May 2024).

Schwerdt, G. and Wuppermann, A.C. (2009). Is Traditional Teaching really all that Bad?: A Within-Student Between-Subject Approach. Working Paper. Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo). Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/30604 (Accessed: 2024).

Stanford University (2023). Teacher-Centered vs. Student-Centered Course Design, Teaching Commons. Available at: https://teachingcommons.stanford.edu/teaching-guides/foundations-course-design/theory-practice/teacher-centered-vs-student-centered (Accessed: 17 May 2024).

Steenhuis, H.-J. and Rowland, L. (2018). Project-Based Learning How to Approach, Report, Present, and Learn from Course-Long Projects. New York, New York: Bishop Expert Press.

Tularam, G.A. and Machisella, P. (2018). Traditional vs Non-Traditional Teaching and Learning Strategies - the case of E-Learning, International Journal for Mathematics Teaching and Learning, 19(1), 129–158. https://doi.org/10.4256/ijmtl.v19i1.21 .

Yew, E.H.J. and Goh, K. (2016). Problem-based learning: An overview of its process and impact on learning. Health Professions Education, 2(2), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2016.01.004 .

↑ Top