Keeping students engaged with elements of flipped, collaborative and adaptive learning techniques

Jana Sadeh

University of Southampton

Published October 2023

Introduction

Higher Education institutions are still feeling the impact of COVID, long after face-to-face teaching and assessment has been reinstated. Student defaults have switched to consuming learning in flexible ways that suit their lifestyle and this has had severe impact on lecture attendance and student engagement. Online video viewing data indicates that students interact with online content the way they consume Netflix shows, bingeing content in short durations in the lead up to assessments and exams, which is typically not the way the module convener intends for it to be consumed. Following a particularly disappointing performance by students in 2021/22 I set about radically shaking up my third-year Public Economics module. I incorporated some of the key lessons that economists have learned from the fields of mechanism design and behavioural economics to achieve increased student performance and engagement.

A key part of the process was focusing on the benefits of flexible lecture delivery learned from COVID. Students appreciate the use of technology that allows them the freedom to dictate the pace of their own learning. This benefit has potential distributional implications, being felt more strongly by students from low socio-economic backgrounds and those who work or have caring responsibilities. However, behavioural analysis shows that students suffer from present bias, and often procrastinate on tasks when they confer disutility. As highly as I think of my delivery of economics content, I cannot believe that this is a positive utility conferring experience that beats the opportunity cost of the many other activities our students choose to engage with. In addition, COVID has damaged peer networks (Grover and Wright, (2022)) which impacts student performance (Boud, Cohen, and Sampson (2014); Butcher, Davies, and Highton (2006)), experience as well as mental health (Johnson and Johnson (2009); Topping (2005)).

This case study is about designing a module that encourages students to regularly interact with the content and with each other in order to improve their experience and their outcomes. This can be achieved by designing a module that has appropriate incentive structures that reward these two elements.

The module design

I took a backward design approach and started with the behavioural outcomes I would like students to display. I identified a clear list of outcomes that the module design needed to achieve.

- Regular interaction with the material being covered each week.

- Flexibility for students to learn at their own pace.

- High student engagement with lectures to develop an interest in the module.

- Collaborative learning to allow for peer support.

- The ability to respond to students' needs for deeper learning.

Having identified these objectives I set out to design the module structure to be incentive compatible, so that the desired outcomes were the ones the students would self-select into in pursuit of their utility (or grade) maximisation exercise.

Module Structure:

- Flipped module design with self-paced videos delivering all the module content.

- Weekly (summative) in-class quizzes worth 10% of the final module grade to confirm consumption and low-level understanding of the recorded content.

- In-class scaffolded collaborative learning exercise.

- 10 min responsive lecture time where students decided what we would spend time discussing each week.

The weekly timetable looked as follows:

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recorded videos and slides released for students to consume at own pace | 1 hour in person lecture:

1 hour masterclass |

The in-class quiz was hosted on Blackboard, our virtual learning environment (VLE). The benefit is that the quiz is automatically graded and combined with the other assessment methods. Students accessed the quiz by either scanning a QR code with their phones or by inputting a website address into a laptop or tablet. They had ten minutes in class to answer ten questions. Students were allowed to refer to the slides and engage in minor consultation with each other, but for the most part they worked quietly and found the questions to be substantially challenging. The average grade students received on this assessment component was 69 out of 100, indicating that the calibration of the challenge was sufficient to assess student learning.

Following the quiz, the students received handouts with a problem set challenge each week. They were seated at round tables to facilitate communication as a group. The handouts evolved over the weeks as students’ feedback was incorporated. They settled into an equilibrium of two sub-questions (this would typically be part a and part b of a four-part exam problem). In addition, they received a very detailed hint breakdown of how to approach this problem. An example of such a handout is attached. The hints were crucial to getting students to discuss the problem between themselves as they were posed as questions that the students could ask each other. They probed deep-level understanding of the content. While students worked on this collaboratively, I roamed the room and facilitated the process. I would stop in tables that were particularly quiet, ask them how they were doing, and provide encouragement or feedback. I made sure they understood that mistakes were expected, that they were key to the learning process, and they never had any negative consequences but always received appreciation for trying something they were not confident in.

The final ten minutes of the lecture varied each week. If students had emailed me about any particular part of the recorded content they wanted revising (which they were encouraged to do) I spent this time revising the content. After mid-term feedback I spent the ten minutes feeding back about the feedback and discussing potential solutions to the problems they raised. Before the exam period we spent this time discussing optimal exam strategy. It was up to the students to decide what they wanted me to talk about.

"Attendance for the in-person lectures stood at around 90% throughout the entire semester, and never dipped except for one week."

What problems were encountered?

There was initial resistance by the students to the format. Students were unfamiliar with flipped lectures and were hesitant about the in-person quiz. Students also worried about what happened when they couldn’t attend class for valid reasons.

Department leads were concerned about the increased administrative burden that might be created by students asking for special considerations (our system of accounting for valid absences) if each lecture contained a summative assessment. Additionally, students have two weeks to switch modules so some may not have had the opportunity to attend the first two weeks.

In order to address these issues a best 8 out of 10 quizzes rule was instituted. This allowed students some flexibility in attending lectures and also reduced the pressure if one week they were unable to keep up with the content and performed poorly on the quiz. At the end of the academic year, I queried the number of special considerations that were raised regarding the quiz component and only two requests were made out of a class of 47 students. We concluded that the quiz did not pose any additional administrative burden.

How did the students respond?

Attendance for the in-person lectures stood at around 90% throughout the entire semester, and never dipped except for one week which coincided with the dissertation submission deadline. This was unsurprising given the quiz component but a very welcome relief compared to the previous year’s attendance.

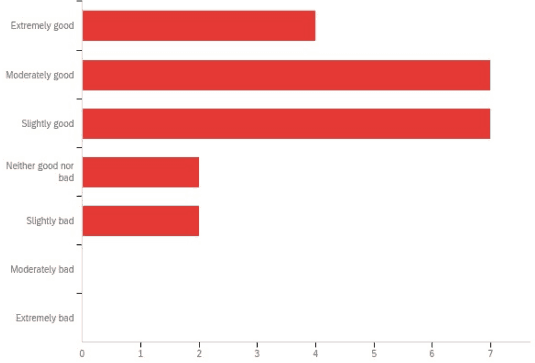

Two formal feedback surveys were conducted: a mid-term and a final feedback survey in weeks 6 and 11 of the 12-week semester. Around 60% of the students responded to the final feedback. The overall satisfaction with the module appears good, with some dissatisfaction being outweighed by those who really liked the module.

Figure 1: Overall Module Evaluation

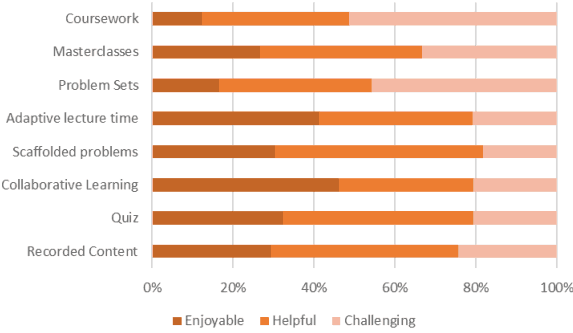

Comparing the different elements of the module structure, students were asked to evaluate each structure on three different dimensions:

- How enjoyable have the following elements been?

- How helpful have the following elements been to your understanding of the module content?

- How challenging have the following elements been?

We can see that the problem sets and coursework are the most challenging parts of the module with the quiz posing a much smaller challenge. The element students enjoyed the most was the collaborative learning and the adaptive lecture elements. The elements that helped them most in the understanding of the module content were the recorded content, the quiz, the scaffolded class problems and the masterclasses.

Figure 2: Strengths of Different Module Elements

Overall each component seemed to achieve what it was meant to do.

In addition, in order to evaluate whether this format was successful in ensuring same-week viewing of recorded content I compare the viewing patterns on our online video system for this cohort and the previous year’s cohort. Figure 3 below shows the views for one particular video. The first half of the chart shows the number of times the video was viewed in 2022 by the previous year’s cohort, while the second half are the views in 2023 by the new cohort. You can see that it took the 2022 cohort from February to June for the students to view this one lecture, whereas the 2023 cohort (that was a smaller cohort) mostly viewed it in the first week with very little spill-over to the second week). This was a pattern that was repeated for almost all the asynchronous videos released.

Figure 3: Views and Downloads of Asynchronous Content

In conclusion, adapting the lessons we learn from mechanism design and looking at making our modules more incentive compatible can be a helpful exercise in ensuring the learning experience is an engaging and productive one. Thinking about how our students are going to respond to the design of the structure of our module, not just the content, can ensure that we can support them to pace their work evenly and to focus their efforts on the elements that will bring them highest return.

References

Boud, David, Ruth Cohen, and Jane Sampson. Peer learning in higher education: Learning from and with each other. Routledge, 2014. OCLC 879460559

Butcher, Christopher, Clara Davies, and Melissa Highton. Designing learning: from module outline to effective teaching. Routledge, 2006. OCLC 1100447916

Grover, R. and Wright, A., 2023. "Shutting the studio: the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on architectural education in the United Kingdom." International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 33(3), pp.1173-1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09765-y

Johnson, David W,. and Roger T. Johnson. “An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning.” Educational researcher 38, 5: (2009) 365–379. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09339057

Topping, Keith J. “Trends in peer learning.” Educational psychology 25, 6: (2005) 631–645 https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500345172

Example handout

Click to expand

↑ Top