Experiential learning, sense of belonging and feedback using Economics games

Antonio Rodriguez-Gil*

Ali Raza & Yi Pang

Leeds University Business School, University of Leeds

Published May 2025

*Corresponding author:

a.rodriguezgil at leeds.ac.uk

1. Introduction

It is common for Higher Education students to report a disconnect between what we teach them and the real world. Our institution, the University of Leeds, has responded to this with a commitment to offer experiential learning activities embedded the Student Opportunities and Futures Strategy (UoL, 2021)[2], SOFS hereafter. We report here our reflections and assessment of introducing an experiential learning activity, in the form of two classroom games, in a final year compulsory module in Economics.[1]

In the first game, students played the role of the Secretary of the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) and were presented with an Excel-based simulation that simulated different potential real life scenarios (eg., downturns, raise in unemployment), and in groups they were asked to experiment with different policy tools and assess their effectiveness. Similarly, in the second game, they acted as the Chair of the Bank of England (BoE), and assessed the consequences of different monetary policies. The policy comparison was also used to raise students’ awareness of institutional differences across countries, which is another of the SOFS commitments.

Our assessment of the intervention shows that 80% of students found that our role playing games were positive for their learning. We also find that games have additional benefits in terms of sense of belonging and peer feedback, as 97% of students found games more conducive to interaction with their peers than standard seminars, which we believe has had a positive effect in developing a sense of belonging.

2. Intervention overview

During 2024/25, we ran two game sessions in a final year compulsory module in Economics. Each of the games asked students to play the role of a different economic policy maker: in the first game, the Secretary of the DWP; in the second game, the Chair of the BoE. Both games were based on Excel spreadsheets that modelled different parts of the economy, drawing from the relevant empirical literature. In the DWP game, the spreadsheet presented a calibrated version of the UK labour market and allowed for changes in labour market policies. Whereas the Chair of BoE game presented a calibrated version of aggregate demand and supply in the UK, with interest rates as the main policy tool. Each game presented students with different potential real life scenarios, where they were asked to experiment with different policy tools, reflect on the outcomes of these policies and (try to) find the optimal policy response. We provide further details on each game below.

In both games, students were asked to play in groups of 2-5 people, to encourage peer interactions and feedback. Further, students were asked to complete a set of questions in MS Forms. This had two intentions: first, to guide and provoke students' group discussion; second, to allow staff to monitor progress in real time and to provide immediate feedback to each group or to the whole class, depending on what was needed. Llavador (2024, ch9) describes a similar structure.

Figure 1. DWP game Key variables, Policy dashboard and Newsfeeds

a) Key indicators

b) Policy dashboard

c) Newsfeeds (click to expand)

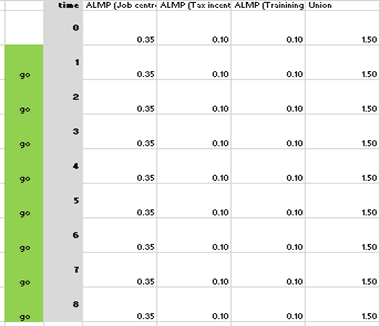

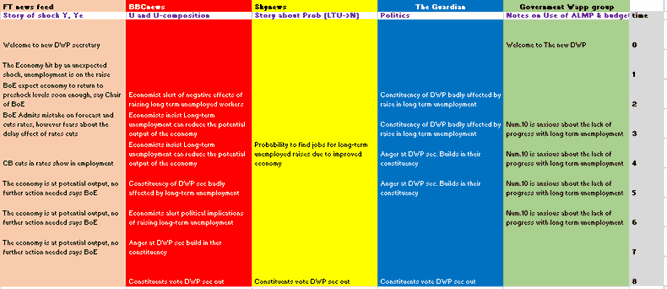

Let’s explain the games in a bit more of detail. In Game 1, the Secretary of the DWP game, we use an Excel simulation purposely built for this exercise drawing from the relevant empirical literature. During the game students were presented with two scenarios: a prolonged downturn and a short-lived one. The spreadsheet presented a dashboard with key indicators of the economy, see Fig 1(a), which students were asked to use to assess the consequences of each scenario. Then students were asked to use the policy dashboard included in the Excel simulation, see Fig 1(b), to experiment with different policies and assess which of them would deliver the best results given the DWP remit of “Maximize employment” (DWP, 2024). In this case, policies available to the Secretary of the DWP included active labour market policies (job centres spending, tax rebates to hiring and training) along with union legislation[3]. The comparison of different policy settings allowed us to draw students' attention to cross-country comparisons in the design of labour market policies.

To make the game more interactive and provide a narrative of the events, the Excel spreadsheet also generated automated news messages that draw students' attention to the key developments, such as the rise of long-term unemployment, or constituents' sentiment, see Fig 1(c). To emphasize the game nature of the activity, the Secretary of the DWP could lose their job depending on the results of its actions, as shown in the last row of Fig 1(c). Students enjoyed this feature a lot.

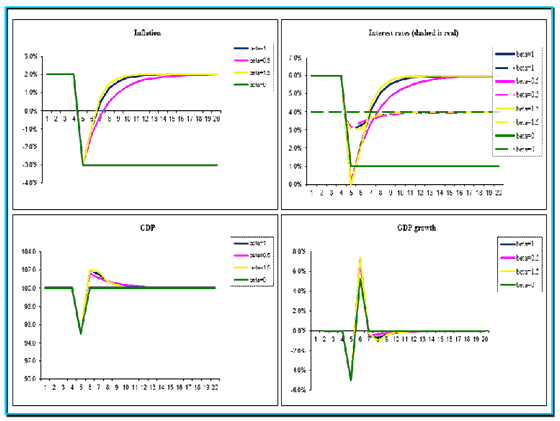

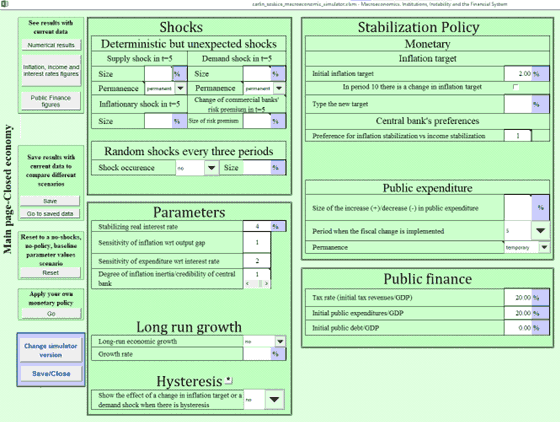

Figure 2. Bank of England policy game, key variables and dashboard

a) Key variables

b) Dashboard

In Game 2, the Bank of England Chair game, we used an Excel simulation provided by our textbook, Carlin and Soskice (2016). This simulation includes a number of plots that allowed students to follow key indicators, such as inflation and output, see Fig 2(a), as well as a policy dashboard where they set up different policies, see Fig 2(b). In this case, students were asked to experiment with different policy settings in response to a temporary downturn. This included changes to the degree of inflation aversion of the central bank and government spending. Again, this allowed use to discuss different policy settings in different countries (or over time), and how this can lead to different outcomes to incorporate an international perspective to the activity.

3. Assessment

To assess the intervention we mainly use the results of a survey that we designed to gather students opinion on the game sessions. We also draw from the university's module evaluation survey. Our survey focused on four areas. One, what do students think of the experiential activity (i.e. role playing as policy makers)? Two, how do students rate peer learning and interactions in these sessions? Three, do they find feedback in these sessions useful? Four, what format is more suitable: a small or a large group setting?

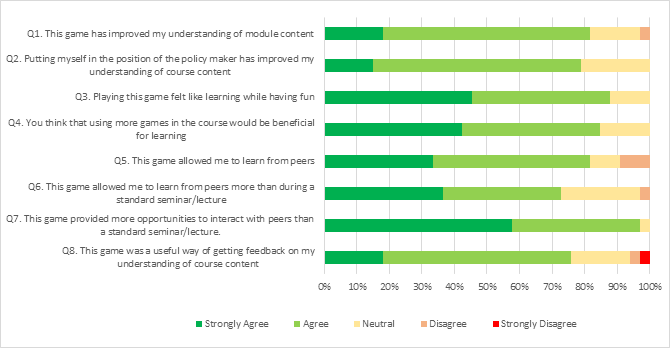

Results were very positive. We start with their overall assessment of the experiential activity, measured in Questions 1-4, see Fig3. Over 80% of students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, that “(Q1.) This game has improved my understanding of module content”. The experiential nature of the games, having to think and act as policy makers, was a key factor to contribute to this understanding, as 78% of students reported that role playing had improved their understanding of the course materials, see Question 2. Similarly, 87% of students found that they learnt while there were having fun, which is also known to be positive for learning (Dichev and Dicheva, 2017). The success of the intervention is also reflected in the large proportion of students, 84%, who think that having “more games” would be beneficial for their learning, see Questions 3 and 4, respectively. These findings are in line with previous literature as per the surveys in Experiencing Economics (2024) and Llavador (2024, ch9).

Students' satisfaction with the games was also reflected in the module evaluation where half of the free-text answers commented positively on the games, for instance they noted that the game had helped them “visualise concepts” or that “simulations were useful in applying the theory in a practical manner”.

Figure 3. Ad hoc survey on game sessions

According to students, games created an environment that was not only conducive to learning, but also to interaction with their peers. 81% of students found that games allowed them to learn from their peers, see Question 5 in Fig 2. Interestingly, 72% report to have learnt more from their peers than in a regular seminar/lecture sessions, see answer to Question 6. In the same line, a resounding 97%, think that games provided more opportunities to interact with peers than standard seminars/lecture, see Question 7. This is remarkable, because standard seminars already encourage students to work in groups following the think-pair-share approach, see Boston (2002). Available literature also finds that games are a useful mechanism to create networks and improve sense of belonging (Braxton et al., 2000, Emerson and English, 2016, Giamattei et al., 2017). Our questionnaire did not ask about stress levels, self-confidence or anxiety about the exam, so we do not have hard evidence to claim a positive impact on students’ mental health. However, considering that students claimed that they had fun, and that games helped them build relations with their peers, we believe games had a positive impact on students’ state of mind in line with Milovanska-Farrington and Mateer (2025). Regarding feedback, students are aware that they received feedback while playing the game, and 75% of them agreed that the “game was a useful way of getting feedback”: see Question 8.

When we asked students to rate the two settings used for the activity, small group (i.e. seminar) and large group (i.e. lecture), 65% agreed or strongly agreed that “the game was more appropriate for small group teaching than in a lecture”. It is also worth noting that the lecture setting seemed less conducive for peer learning and feedback, as during this session, only 57% of students reported to have learnt from their peers and only 58% found the feedback received been useful. This was also reflected in the module evaluation were students suggested to “keep the simulation exercises to seminars”.

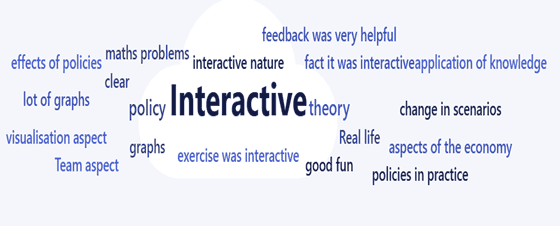

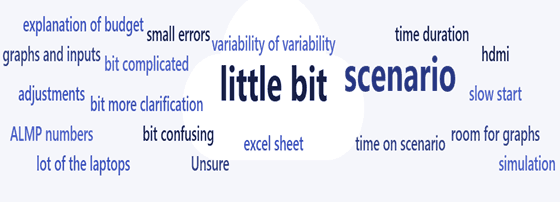

Figure 4. Liked and disliked most

a) Liked the most

b) Disliked the most

Finally, we asked students what they liked and disliked the most, and as Fig 4a shows, they clearly valued the interactive nature of games, which was one of the main objectives of the intervention, to provide an interactive learning tool. Comments on what they disliked the most, reported in Fig 4b, reflect small issues in the design of the Excel sheets rather than questions about the experiential activity. This was also reflected in the module evaluation were students referred to games as an “interactive” or “engaging activity”.

Staff delivering sessions also felt very positively about it, highlighting how much laughter they have heard during all sessions. We reflected on how that made the teaching more rewarding as already highlighted by Llavador (2024, ch9).

4. Summary

We have assessed the introduction of an experiential activity, with two games, in a final year compulsory module in Economics. In the first game, students role play as the Secretary of the DWP and in the second one, as the Chair of the BoE.

We find that a very large proportion of students, 80%, found games were positive for their learning, with role playing contributing substantially to it. Students also found that games created a better environment for peer learning and nearly all of them, 97%, believed it provided more opportunities to interact with peers. Thus, it is clear that games are a useful tool to enhance students learning. It also allowed us to contribute to the commitments of the SOFS in terms of experiential learning and sense of belonging. The experience was also very rewarding for staff, who reported never hearing so much laughter in their classes. Finally, we believe that future research should aim at investigating the link between games and students' mental health.

Bibliography

Boston, C., 2002. The Concept of Formative Assessment. Eric Digest ED470206. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED470206

Braxton, J. M., J. F. Milem, & A. S. Sullivan, 2000. “The influence of active learning on the college student departure process: Toward a revision of Tinto’s theory.” Journal of Higher Education 71 (5): 569–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/2649260

Carlin and Soskice, 2016. "Excel-based macroeconomic simulator webpage." OUP. Last accessed 26 March 2024. https://global.oup.com/uk/orc/busecon/economics/carlin_soskice/student/excelsimulator/

Dichev, C., & D. Dicheva, 2017. Gamifying education: what is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: a critical review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 14 (1): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0042-5

DWP, 2024. The Department of Work and Pensions. "About us. Priorities". Accessed September 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-work-pensions/about#:~:text=for%20the%20taxpayer-,Priorities,financial%20resilience%20in%20later%20life

Emerson & English, 2016. Classroom experiments: Teaching specific topics or promoting the economic way of thinking?, The Journal of Economic Education, 47:4, 288-299, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2016.1213684

Experiencing Economics, 2024. CoreEcon Economics for changing the world. Last accessed 26 March 2024. https://www.core-econ.org/project/experiencing-economics/

Giamattei and Llavador, 2017. Teaching Microeconomic Principles With Smartphones – Lessons From Classroom Experiments With Classex (October 4, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3157026 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3157026

Llavador, H., 2024. "Experiments for Teaching Economics". Chapter 9 in Al-Bahrani, A., Chaudhury, P., and B.J. Sheridan, editors, Teaching Economics Online. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781803921983.00020

Milovanska-Farrington, S., and D. Mateer, 2025. Using engaging activities to enhance students mental Wellness in introductory Economics classes. IZA Discussion Paper. No.17637. https://www.iza.org/en/publications/dp/17637/using-engaging-activities-to-enhance-student-mental-wellness-in-introductory-economics-classes

Olczak, M., 2022. Using online games to teach Economics. Inomics Teach. Last accessed 26 March 2024. https://inomics.com/teach/using-online-games-to-teach-economics-1526444

Sutcliffe, M., 2020. “Simulations, Games and Role-play”. In The Handbook for Economics Lecturers. Ed. by P. Davies. Last accessed 26 March 2024. https://www.economicsnetwork.ac.uk/handbook/printable/games_v5.pdf

University of Leeds (UoL), 2021. Student opportunities and futures strategy. Last Accessed 13 May 2025. https://leeds365.sharepoint.com/sites/StudentOpportunitiesandFutures/SitePages/Introduction-to-the.aspx

Notes

[1] This project was partially funded by the Curriculum Redefine Experiential Learning Seedcorn fund for which we are thankful.

[2] The intervention was also motivated by the fact that despite very high scores in the module evaluation (+80s/100), previous students reported that the module was missing interactive elements.

[3] We are currently working on a further iteration of the Excel sheet that will allow students to also modify benefits generosity.

↑ Top