A double-act to teach threshold concepts

Introduction

Co-creation may include activities where students directly collaborate with academics on the design, creation, delivery and evaluation of teaching resources and practices; this can also include curriculum, syllabus and assessment development. Bovill et al. (2016) have highlighted the advantages and challenges connected to co-creation. Despite the costs connected to it, usually connected to the necessity to relinquish some control to students over key aspects of the design and delivery of their modules, and the efforts to empower students to become effective co-creators, partnership and co-creation can unlock exceptional benefits.

Cook-Sather (2014) describes in detail how introducing forms of student/staff partnership and co-creation may foster the principles of respect, reciprocity and responsibility, sometimes referred to as the “3R” of partnership, which are essential for student engagement and active learning. Taken together, the broad integrative nature of partnership and the specific contributions of the "3R" of co-creation can provide a critical input to the development of students' soft skills (e.g. confidence in their abilities) and their motivation, ultimately turning student-customers into co-creators and responsible members of a learning community. In this sense, co-creation could be a key contributor to establish a community of learning with students.

An example of intervention in an intermediate microeconomics module

In what follows, we describe our experience with co-creation in an intermediate microeconomics module at The University of Manchester. The module is a second year 10-credit compulsory unit for undergraduate economics students. It also caters for finance, business and politics. There are more than 400 students registered to the module, with a significant portion of international students.

In December 2020, we released a call for student volunteers interested to co-create, during summer 2021, resources and practices to be released to the new class of 2021/22. Here we shall describe the case of the student, co-author of this piece, who agreed to co-teach a portion of a live lecture.

Co-creating the material

We decided to cover an interesting extension of the standard Cournot duopoly game. During their degree, students are offered multiple opportunities to engage with this model. It is, however, the case that students are in general exposed exclusively to the linear version of the model, in which two firms, say firm 1 and firm 2, face a linear demand P = a − b(Q), where a > 0, b > 0 and Q = q1 + q2, qi ≥ 0 describing the quantity supplied by firm i (i = 1,2), and linear costs Ci qi = ci qi, a > ci > 0.

The key advantage of the model, namely the existence of an easy-do-derive unique Nash equilibrium, may also be one of its drawbacks from a pedagogical point of view; students repeatedly exposed to this linear rendition tend to assume that the linear analysis (and its unique equilibrium) are the only possible outcomes of the model. However, introducing quadratic production costs in a standard Cournot duopoly with linear demands could open the door to the existence of multiple equilibria.[1] The possibility that a model may not provide unequivocal answers nor a simple lens to interpret a variety of aspects of firms’ strategic behaviour presents the typical features of a threshold concept.[2] Therefore, we decided to expose the class to the following example.

Demand, costs and profits would be given by:

P = 1− q1 − q2

Ci(qi) = ci qi + ei qi2

To further simplify the analysis, we imposed 0 < c1 = c2 = c < 1 and −1 < e1 = e2 = e < −½. The restriction of the set of feasible values of parameter e ensured the existence of multiple equilibria.[3] Given the symmetry of the model, we could focus, for example, on the reaction of firm 2:

(1)

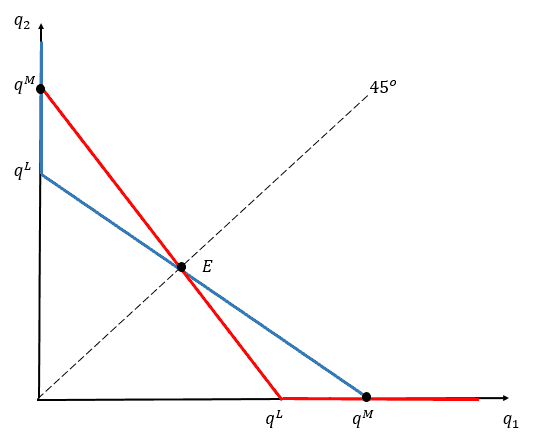

Graphically, the best response functions of the two firms (blue graph for best response of firm 2 and red graph for best response of firm 1) are reported in figure 1. is the quantity chosen by a monopolist. qL = 1 − c is the quantity that would induce a rival to produce a quantity equal to zero to avoid losses.

Figure 1: Firms' best response functions when −1 < e < −½. Blue graph: best response of firm 2. Red graph: best response of firm 1.

When −1< e < −½, qM > qL and the best response functions interest in three locations on the plane: equilibrium Ewhere both firms supply a positive quantity, and equilibria {0, qM} and {qM, 0}, when monopoly is an outcome of strategic competition. A Mathematica notebook with the algebra and the diagrams was also co-created.

When −1< e < −½, qM > qL and the best response functions interest in three locations on the plane: equilibrium Ewhere both firms supply a positive quantity, and equilibria {0, qM} and {qM, 0}, when monopoly is an outcome of strategic competition. A Mathematica notebook with the algebra and the diagrams was also co-created.

Co-creating the delivery

The challenge in front of us was to find a way to discuss the insights of the model with quadratic costs and the equilibria highlighted in figure 1 that would not confuse or discourage some of the students. Of course, one way to go could have been to give the co-creating student the traditional role of guest co-lecturer; however, we decided to go for a more impactful and, ultimately, fun approach: role play[4]. The lecturer would introduce the standard linear Cournot model to the class and the student co-creator would pretend to be one of the students attending the lecture. Before the lecture, we carefully planned our double-act.

Here is how it went. The lecturer taught the lecture as usual, while the student co-teacher sat among the other students. When the lecturer completed the discussion of the standard linear model and pretended to move to another topic, the student interrupted the lesson to ask a question. They were not convinced at all that the insights of the linear case considered in class were that meaningful; they had a go at the case with quadratic costs and they were concerned with the existence of multiple equilibria. This kind of input from students, especially UG, is rather rare and, of course, it created some surprise among the other students and increased attention in the class. After pretending some surprise too, the lecturer asked if the student would have considered showing their notes to the rest of the class, to which the student agreed and showed on the visualiser the derivation of the best response function (1); at that point, the lecturer commended the student and pretended to have, by chance, a useful Mathematica notebook to discuss the graphical analysis as reported in Figure 1.

The interaction with the student and the discussion of the existence of multiple equilibria further increased the level of attention in the class; this was created, in part, by a certain degree of anxiety that these more advanced issues may be part of the final exam, but also by a genuine interest in the discussion: it was not always the case that the standard assumptions of a model would be critically considered, especially in a discussion initiated by a student.

It was time to tell the audience the truth: this lesson had a bit of "theatre" and it was a carefully planned product of co-creation. The class reacted with a round of applause (perhaps also prompted by the reassurance that the Cournot model with quadratic costs would not be part of the exam). The resources were then uploaded on our VLE; the lecture, as standard, was also recorded and accessible asynchronously to the class.

First Impressions

The instructor

Co-teaching with a student gave the lecturer an effective and engaging way to expose the class to threshold concepts. In addition, engaging and co-creating with the student in an informal and honest way allowed the lecturer to experience directly the student’s views on the syllabus and delivery of the module, their impressions of the way other students felt and engaged with their learning journey in microeconomics.

The student co-creator

Co-teaching with a lecturer gave the student a deeper insight into advanced concepts. It made him realise the amount of research and work that goes into presenting an intermediate microeconomics course. Moreover, co-creating with the lecturer in an informal and friendly way allowed the student to develop important soft skills. Moreover, the partnership provided the student with exposure to academic life which reinforced an interest in pursuing a PhD.

The class

After the lecture, we received a few encouraging messages, like the following two:

I definitely enjoyed [student's name]'s contribution [...]. Although a little complex for me, I was still interested in watching [student's name] play with the model in a way I had not thought about.

...please thank the student who you did a bit of acting with, haha, it helped me a lot to understand how to make more simple models realistic. P.S.: great acting skills as well.

Also, despite no official call from the lecturer, after the lecture eight students requested to collaborate and co-create resources for next year.

Conclusions

Co-creation and co-teaching are definitely an experience that we are keen to repeat and further develop. Here are some lessons that we have learnt.

From the instructor perspective.

- It is important for both co-creating partners to have a clear understanding of the objectives, rules, costs and benefits of co-creation. It is OK to spell them out regularly and to consider regular evaluations of the partnership.

- Co-creation implies some form of partnership and, in turn, partnership implies some degree of emotional commitment. Instructors should not take offense if students decide to stop collaborating and, as much as possible, they should try to honestly discuss and internalise the challenges faced by students in the planning.

- At the same time, partnership means taking responsibility and facing challenges. When appropriate, students should be encouraged (and supported) to operate outside of their comfort zone. This will help them developing soft skills and confidence.

From the student perspective.

- As this project is an extra-curricular initiative, it is important to understand that participants are likely not to be as punctual with their work as they usually would be with their compulsory academic commitments.

- The student may find interacting with the lecturer in an informal context outside of the classroom unusual at first. Honesty and trust are essential to create a positive co-creating partnership and make the most out of this experience.

- Both the lecturer and the student should be adaptable and flexible while co-teaching. Like during any live lecture, a number of unforeseen events may occur. For instance, a hard question from the audience, or, as in our case, the student's phone ringing in the middle of co-teaching.

- In order to encourage more students in taking part in co-creation, it is essential to explain clearly the set of intended learning and employability outcomes for the students involved. Indeed, when the student mentioned partaking in the co-creation and co-teaching in his Masters’ application interviews, he received extremely positive reactions, as the interviewers showed a keen interest in this experience.

Notes

* The University of Manchester, Economics.

** The University of Manchester, BAEcon Finance (Hons), 3rd Year.

[1] See Bischi et al. (2009).

[2] Threshold concepts are subject concepts that may be transformative, irreversible, integrative and troublesome, when approached by students. See Davies and Mangan (2007) and Goebel and Maistry (2019).

[3] If e > 0, then costs would be convex and the model would still generate a unique equilibrium. −1 < e < −½ would ensure the concavity of the profit functions, despite the concavity of the costs, and the existence of multiple equilibria.

[4] See Davis (2019) and Morroni and Soliani (2022).

References

Bischi, G. I, Chiarella, C., Kopel, M. and Szidarovszky, F, (2009), Nonlinear Oligopolies - Stability and Bifurcations, Springer. OCLC 652654875

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., Felten, P., Millard, L. and Moore-Cherry, N. (2016), Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student−staff partnerships, Higher Education, 71, 195−208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4

Cook-Sather, A., (2014) ‘Student-faculty partnership in explorations of pedagogical practice: a threshold concept in academic development’, International Journal for Academic Development, Vol. 19, No. 3, 186−198. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.805694

Davis, M. E. (2019), Poetry and economics: Creativity, engagement and learning in the economics classroom, International Review of Economics Education, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2019.100155

Davies, P., & Mangan, J. (2007). Threshold concepts and the integration of understanding in economics, Studies in Higher Education, 32(6), 71 https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701685148

Goebel, J. and Maistry, S. (2019), Recounting the role of emotions in learning economics: Using the Threshold Concepts Framework to explore affective dimensions of students’ learning, International Review of Economics Education, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2018.08.001

Morroni, M. and Soliani, R., (2022), Theatrical readings as a means of learning economics, International Review of Economics Education, 39, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2021.100229

↑ Top