Jon Guest, Karishma Patel, and Robert Riegler

Aston University Published July 2023

Background

The use of assessed group work continues to raise significant challenges. Although the pedagogic benefits have been widely discussed in the literature, students often express reservations about its use on their courses. Where assessed group work is used, many students argue that it should be designed so that the individual marks awarded closely reflect any variations in the contributions of different team members.

Therefore, tutors need to find an effective way of measuring individual contributions to group work and then use this measure to adjust the group work mark into individual grades. This creates a couple of challenges. Firstly, a method needs to be found to deal with the issues created by asymmetric information as it is impossible for tutors to perfectly observe the contributions of different group members. Secondly, an adjustment mechanism needs to be implemented that is both transparent and objective. One approach is for tutors to use peer evaluation where students make evaluative judgements about the contributions of their team members and provide numerical scores. Students are clearly in a much better position than tutors to observe the study behaviour and contribution of different team members. The numerical scores can also be used to design an adjustment mechanism that is both clear and easy to understand.

The implementation of a peer evaluation scheme in a large first year undergraduate module

In 2019-20 a new core first year module, Applied Topics in Economics, was introduced onto the BSc Economics programme at Aston University. As part of the assessment, students had to complete a piece of group work. The task for the groups was to write a 2500-word consultancy project that covered the following:

- Identify a topical issue then analyse and explain how relevant economic theory could help the client gain a better understanding of the issue/problem.

- Find relevant data to help support the analysis and present this data in an effective manner using the skills developed in the Statistics for Economics module.

- Analyse the impact of different possible policy options. This includes some evaluation of current policies, previous policies and approaches taken in other countries.

Students were allocated into groups on a random basis. Self-selection was judged to be less appropriate for a first-year module where many students have not met many of their peers. The consultancy report counted for 50 per cent of the module mark.

Peer evaluation schemes vary in a number of important ways. The design of the activity introduced into the Applied Topics in Economics modules had the following characteristics:

- Individual marks (IM) were derived from the overall group mark (GM) in the following manner:

IM = α × GM + (1 − α) × GM × CI

Where:

α = the weighting of the group work mark awarded to the students equally i.e. irrespective of any measure of their individual contribution.

(1 − α) = the weighting of the group work mark that is adjusted based on a measure of the individual student’s contribution

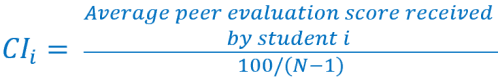

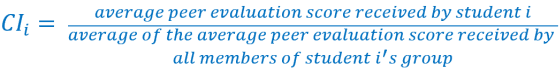

CI = The contribution index which is a measure of the individual student’s input into producing the group work using the peer evaluation scores.

- A fixed-point (FP) scheme was employed where students had to allocate 100 effort points between their team members. The contribution index for each student was then calculated in the following manner where ‘N’ is the group size.

A fixed point (FP) scheme was chosen as it was considered to have numerous advantages over other designs. For example, it is easy for students to understand, limits the opportunities for strategic gaming and reduces the potential for leniency bias.

- Self-evaluation scores were not collected and included in the contribution index over concerns that some students might deliberately overestimate their own contribution scores to inflate their marks.

- Forty per cent of the GM for each student (1 − α) was adjusted using the contribution index calculated from the peer evaluation scores. Sixty per cent of the group work mark (α) was awarded equally.

- The tutors chose TEAMMATES to implement and manage the scheme. TEAMMATES is free-to-use software which enables students to provide peer evaluation scores when completing group-work. It is easy to use and does not require students to have a login as they submit their peer evaluation scores via a unique link. When the tutor releases the peer evaluation exercise, the software automatically sends this link to their university e-mail accounts. Once the deadline for the peer evaluation activity has passed, tutors can access the scores and download the data to Excel.

- TEAMMATES has a number of visibility settings for the peer evaluation scores. The option chosen by the module leaders was ‘Visible to instructors only’.

- The students have to provide a single peer evaluation score for each team member. They did not have to score individual criteria which then need to be aggregated to produce an overall score.

- The peer evaluation exercise was completed twice. On the first occasion it was completed four weeks before the final submission date for the consultancy report. This was solely for formative reasons so students received some developmental feedback on their performance which they could act upon. The second occurrence was after the submission date for the consultancy report. These scores were used to calculate the contribution index and adjust the final group mark into individual grades. The students did not know their group mark when they completed the second peer evaluation exercise.

- The automated e-mail reminder function was used in TEAMMATES to remind those students who had yet to submit their peer evaluation scores. This e-mail explained the implications of not completing the exercise with the following wording — Any individual who fails to submit their final peer evaluation scores/comments will expect to receive a mark of zero for the 40 per cent of the group mark reflecting their contribution.

Evaluating the impact of the scheme

As part of a Learning and Teaching Project at Aston University, two focus groups consisting of ten students were organised in November 2022. These focus groups investigated the students’ perceptions of (a) assessed group work and (b) the peer evaluation design implemented by the module team. Two final year students were paid to chair and transcribe the groups to encourage honesty on the part of the participants. The direct involvement of any members of the module team in the process runs the risk that the student comments will not reflect their true beliefs because of marker-influence concerns i.e. impression management bias. For example, students may avoid making negative comments over concerns it will adversely influence the assessment judgements of the tutor.

Some of the key themes that emerged from these focus group were as follows:

- The TEAMMATES software and system for allocating effort points was easy to understand. However, there were some issues with the way the peer evaluation scores were displayed which led to a lack of transparency over the adjustment mechanism.

- Although there were some disagreements over the appropriate size of 1 − α the majority of participants thought it should be lower than 0.4.

- A general concern that many students focussed on trying to game the system and a perception of widespread collusion between some group members when awarding the peer evaluation scores.

- A lack of engagement with the formative peer evaluation activity.

- Some frustration with having to award a fixed number of effort points. With the FP design used in the module students only judge the relative performance of each team member against other team members. The frustration this causes is illustrated by the following representative comment from the focus groups:

Student B: I think it was a bit pointless because, say I thought person A contributed more than person B, I have to give them more points even if they contributed less than what I did.

Changes implemented in 2022-23

In response to this feedback the module team made the following changes to the design of the peer evaluation scheme in 2022-23.

- Four categories of assessment criteria were introduced to better guide students on how to peer evaluate their team members. The four criteria were:

- The level of participation and contribution in group meetings

- The completion of agreed tasks

- The quality of the work completed

- Group management skills

The students scored their team members on each of these four criteria on a five-point scale. There scores were not used to calculate the contribution index, i.e. they had no direct impact on the final marks. The purpose of the criteria was to provide students with more guidance on how to award the fixed number of effort points which were then used to calculate the contribution index. For each criterion, a simplified version of a behaviourally anchored scale was used as opposed to a Likert scale.

A greater amount of class-time was used to explain the peer evaluation scheme and the assessment criteria. Tutors devoted 30 minutes at the start of a lecture to explain the scheme and answer any questions.

- The weighting of the contribution index was reduced from 0.4 to 0.25.

- An element of self-evaluation was included in the peer evaluation activity on TEAMMATES to encourage greater self-reflection – an important graduate skill. However, the scores were not included in the contribution index

- The design of the first formative only peer evaluation exercise was changed so that it was the same as the one used for summative purposes at the end of the module.

- A new module leader changed the assessment from a written group consultancy report to a group video.

- Did the students believe that the criteria were appropriate? Could the students co-create different criteria?

Preliminary analysis of the 2022-23 results

There were 179 students enrolled on the module in 2022-23. Thirty-one groups were created with the majority of these having six team members. Only four students (2.2 per cent) failed to submit their peer evaluation scores which suggests that the reminders and penalty worked effectively. The following section will focus on (a) the assessment criteria (b) the distribution of effort points awarded and (c) the impact of the peer evaluation scores on the distribution of the marks.

Assessment criteria

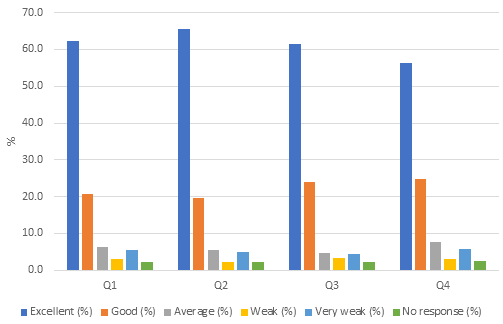

Figure one below illustrates the distribution of the scores across the 4-category assessment criteria

Figure 1 – the distribution of scores across the criteria (n = 860)

Notes:

- Q1: Level of participation and contribution in group meetings

- Q2: The completion of agreed tasks

- Q3: The quality of the work completed

- Q4: Management skills

This figure shows how the majority of students gave their team members high scores across all four criteria. For each marking criteria, more than 81 per cent rated their peers "excellent" or "good". A Chi Squared test indicates that there were no significant differences between the number of positively evaluated students across the different criteria (χ2(3) = 1.19, p-value = 0.75). This could be evidence of leniency bias.

The distribution of effort points awarded

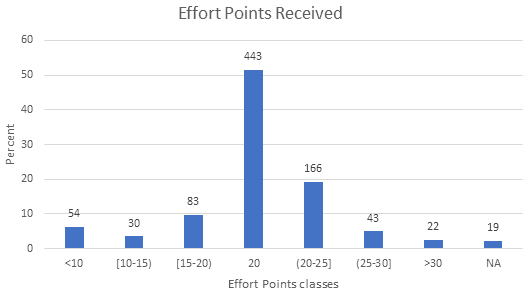

In 7 out of the 31 groups (22.6 per cent), all team members distributed the effort points equally[1]. One interpretation of these results is that those 7 teams worked together effectively with the peer evaluation activity incentivising all team members to contribute equally. However, it could also be caused by an ineffective peer evaluation scheme with students not engaging with the process and/or the process suffering from leniency/centrality bias.

What happened in the other groups where team members did not distribute points equally? Was there limited variation around 20 points or did the students in those groups use the full marking scale? Table 1 provides the answer. In 5 groups (16%), there was limited variation, and in the remaining groups there at least moderate variation. In six of the groups (19%) the standard deviation was greater than 9, indicating a very large dispersion in the awarding of effort scores.

Table 1: Within-Team variation of peer-scores received by each student

| Std. Dev. Categories | Range | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| No variation | 0 | 7 | 22.6 |

| Little variation | (0,3] | 5 | 16.1 |

| Moderate variation | (3,6] | 8 | 25.8 |

| Large variation | (6,9] | 5 | 16.1 |

| Very large variation | > 9 | 6 | 19.4 |

| Total | 31 | 100 |

Figure 2 illustrates the breakdown of the peer evaluation scores received by all the students. With 19 missing observations, the overall sample size is 841. Twenty effort points (equal contribution) was by far the most common peer evaluation score. This accounts for over 50% (443) of all the observations.

Figure 2 – The distribution of the individual peer scores received by each student

The figure also shows that many students did use a wide range of marks with 54 (6.4%) awarding scores of below 10 effort points. There was also a tendency to use round numbers with 10, 20, 25 and 30 effort points being the most common.

The impact of the peer evaluation scores on the distribution of the marks

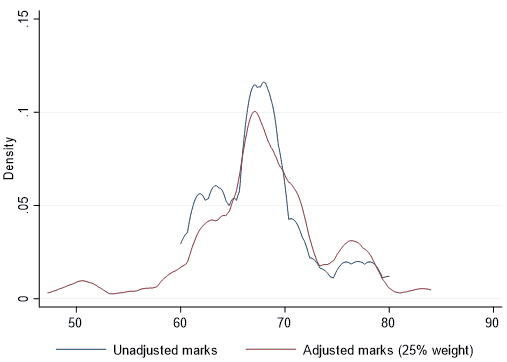

The weighting of 25 per cent of the group work mark based on the contribution index led to 27 students gaining or losing 5 percentage points compared to the outcome where 100 per cent of the group mark is allocated equally. The largest single loss was 17 percentage points whilst the largest gain was 10 percentage points. The impact on the distribution of marks is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 – The distribution of the marks

This figure shows k-density functions to compare the distributions of the unadjusted marks and the marks which have been adjusted by the contribution index. The unadjusted marks distribution was rather narrow, and all marks were within the range of 60% to 80%. Adjusting marks using peer evaluation scores led to more variation, with marks ranging from 47% to 85%.

Future work

Focus groups and a survey will be used to investigate the following issues:

- Did students use the assessment criteria when awarding effort points?

- To what extent did the students exert cognitive effort when trying to evaluate their team members on each criteria? Did they find some criteria easier to score than others? Did the scores suffer from centrality/leniency bias?

Statistical analysis of the peer evaluation scores will be undertaken to estimate the incidence of collusion. These results will be presented at the Developments in Economics Education Conference at Heriot Watt University in September 2023.

Also, in response to some of the frustrations expressed by students with having to allocate a fixed number of effort points, the following variable point scheme will be trialled on some other modules on the BSc Economics degree programme.

With the design of any peer evaluation scheme, one of the key aims is to provide students with incentives to truthfully reveal their observations about the contributions of their team members. However, one interesting feature of a variable points scheme is that it provides students with incentives to misreport observations without having to enter into any formal or tacit agreements with other team members. The Nash equilibrium for narrowly self-interested students, who only care about their own marks, is to award their team members the lowest scores possible. Different authors (for example Spatar et al, 2015) have made various suggestions about how to modify the calculation of the contribution index to address this issue. One issue with these modifications is that as they become more complex, they reduce the transparency of the system and make it more difficult for students to understand how their marks are calculated. Chowdhury (2020) also argues that they are only effective if students are indifferent about the marks of their peers i.e. they don’t have social preferences.

One method of modifying the contribution index in a variable points scheme will be trialled and evaluated in a module at Aston University. The results will be discussed in a future case study on this website.

References

Bushell, G. 2006. Moderation of Peer Assessment in Group Projects. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. vol 31, no.1, pp. 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500262395

Chowdhury, M. 2020. Using the method of normalisation for mapping group marks to individual marks: some observations, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 45, no 5, pp. 643-650, https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1686606

Li, L. 2001. Some Refinements on Peer Assessment of Group Projects, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293002002255

Margin, D. 2001. Reciprocity as a Source of Bias in Multiple Peer Assessment of Group Work. Studies in Higher Education. vol 26, no 1, pp. 53–63. http://doi:10.1080/03075070020030715

Sharp, S. 2006. Deriving Individual Student Marks from a Tutor’s Assessment of Group Work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. vol. 31, no 3, pp 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500352956

Spatar, C., Penna, N., Mills, H. Kutija, V., and Cooke, M. 2015. A robust approach for mapping groups marks to individual marks using peer assessment, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 40, no. 3, pp 371-389. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.917270

Notes

[1] To ensure that we can compare the effort points between groups that have 5 or 6 students, we rescaled the effort points for students that are part of a group of 5 by multiplying them by a factor of 0.8.

↑ Top