Steve Cook

Swansea University

s.cook at swan.ac.uk

and Duncan Watson

University of East Anglia

duncan.watson at uea.ac.uk

Published February 2023

Summary

“Some people talk in their sleep. Lecturers talk while other people sleep.” Camus (Long and Lock, 2014).

Is the perception of the dull Higher Education lecture, fed via ‘Death by Powerpoint’, now old news? Encouraged by an immediate exposure to remote learning methods through pandemic panic, the sector has vigorously deployed a myriad of blended learning methods. In particular, enabled through a bank of lecture capture resources, supposedly active learning methods are routinely utilised. ‘Flipping the Classroom’, for example, continues to dominate innovation throughout the sector.

The evidence, mind you, suggests that flipping- if not implemented with any pedagogical finesse- can be a futile exercise which only reinvigorates shallow entertainment (Cook et al., 2019; Webb et al., 2021). While there may be marginal gains through improved module evaluations, the overall learning experience then wallows in stagnancy. How might we safeguard better outcomes? We investigate this issue through the activities adopted within a flipped module. Here, we will champion the humble crossword. Referring directly to quantitative methods, which is often unfairly portrayed to be a more mundane experience, we show how it could support more effective learning. Our case study portrays how we can go beyond ‘time filling’ and incorporate cognitive understanding to develop a ‘meaningful learning’ experience.

An Active Learning Introduction

An outdated view of the lecturer paints them as a pedagogue delivering a didactic, or unidirectional, approach to learning. To highlights its deficiencies, consider an extreme portrayal of this approach where: the audience should be quiet, except for the twang of pen nibs as they feverishly duplicate everything presented by the expert on display; and obedience is insisted upon, with any chatter disrupting the tranquil atmosphere spawning demands for the culprit to vacate the premises. While presenting an exaggerated depiction of the ‘traditional’ lecture format, it is unsurprising that naïve approaches based upon the one-way transmission of information have received criticism (e.g. MacManaway, 1970) and academics have pursued engagement-enhancing innovations. Recently this has included presentation of standard material via vignette videos created to support remote delivery under COVID-prompted remote conditions. With these uploaded to the institution’s favoured VLE, lecturers can undertake an almost costless form of ‘Flipping the Classroom’. However, some lecturers will ask: ‘what else should I provide to encourage interactivity?’

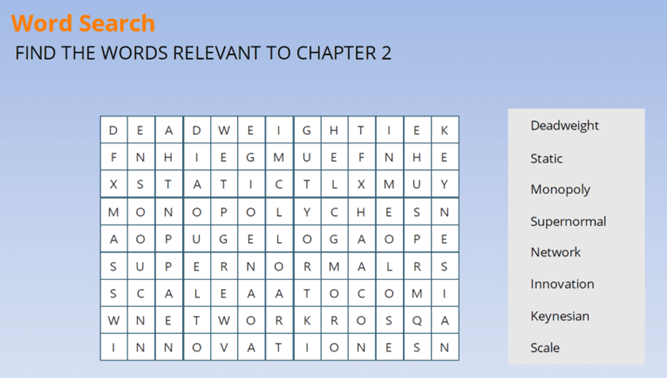

One popular response has been to test knowledge by presenting workshop puzzles. An example is the introduction of Word Search. Asked to read a chapter of material prior to the learning event, a print-out is given to all students. After 10 to 15 minutes to look for key economic terms, the lecturer then checks which words have been discovered. They are pursuing multiple aims here: evidence that the chapter has been read; appreciation of the key concepts; and revealing how revision activities might be structured. Do they need to give more detail over these concepts? Should they use the exercise to introduce further activities, from multiple choice tests to samples of examination questions? The lecturer can spend considerable effort convincing themselves that their workshop methods are cunningly designed.

These methods, while generating a more jovial workshop environment, saunter towards the superficial. Unless there is more elaborate consideration of active learning, it can be diminished to being nothing more than a ‘time filler’. So what is active learning?

Active learning is a topic which undoubtedly sings out in the education literature. While gaining in prominence in recent years, it can be traced back to Crawford (1925) (see Proud, 2022). Nevertheless, like many notions in academia, it can be an elusive concept. Prince (2004) sought, but failed, to secure a consensus in definition. Nevertheless, you might want to refer to Bonwell and Eison (1991). The discussion there emphasises: ‘doing’ on the part of students; increasing engagement; the development of higher-order skills; and an alternative to one-way delivery from the lecturer to the learner. The reference to developing ‘higher-order skills’ is interesting here as it provides a link to the discussion of ‘meaningful learning’ provided by Mayer (2021).

Meaningful learning is an important concept within education as it refers to the development of an ability to both retain and transfer, or apply, knowledge. Mayer (2021, p. 21) argues that active learning provides the ‘best way to promote meaningful learning outcomes’. However, here the involved nature of active learning becomes apparent as Mayer (2021) notes that active learning may be effective or ineffective, and activities can be considered in terms of their behavioural and cognitive elements. Below is a useful disaggregation provided by Mayer (Mayer, 2021, Figure 1.2, p.22):

| Level of cognitive activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Level of behavioural activity | Low | Ineffective passive instruction | Effective passive instruction |

| High | Ineffective active instruction | Effective active instruction | |

So, how does Mayer (2021) distinguish between behavioural activity and cognitive activity? A crucial distinction is that only the latter promotes meaningful learning. It is here, therefore, where you must be careful in how you design your activities. While a learner might be behaviourally, or physically, active in a simple Word Search, this may not involve the cognitive processing sufficient to generate meaningful learning.

Championing the Crossword

The use of crosswords in the learning experience appears in the education literature (see Patrick et al., 2018). Their value as a general testing resource repeats the Word Search rhetoric. They are particularly useful for recapping, again helping to shape revision sessions. But, by referring to Mayer (2021), we can shape a more thorough endeavour. A particularly attractive feature of crosswords is that they support both behavioural and cognitive activity. While we want to deliver ‘meaningful learning’, we argue that there remains value in pursuing behavioural activity. First, behavioural activity can serve as a ‘warm-up exercise’ when starting a revision or recapping session. A simple definitional exercise, such as completing an incomplete statement in relation to a topic, can act as an ice breaker to gently re-introduce a topic. Second, a simple exercise involving behavioural activity can serve as a precursor for a subsequent more involved exercise on the given topic. However, ensure that you do not neglect such cognitive activities! Crosswords, by setting clues that involve the consultation of scholarly research (and reference to tables and empirical output) or other relevant materials, can ensure that pre-existing knowledge has to be synthesised with new information. Let’s present an example.

An Illustrative Example

In this example we want to both demonstrate the use of crosswords in the teaching of economics/quants and pick up on the above discussion of behavioural and cognitive activity. While you might want to use available online crossword creators, let’s summarise the basic operational issues that we adopt. The grid below is constructed just using Excel. So you need to: highlight rows and do some dragging (or adjust rows using ‘Row Height’); highlight columns and do some dragging to make cells look square; add some numbering; and then throw in some colour to distinguish the cells to be filled from the others. Job done!

| 1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 3 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 5 | 6 | |||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||||||

| 10 |

The clues to this crossword are given below:

Across

- The Hodrick-Prescott filter involves minimisation of a two-part expression involving the fit and ____ of its proposed trend. (10)

- Consider Table 3 in Leybourne (1995, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics). The results presented provide evidence of the DFmax test exhibiting greater ____ than the Dickey-Fuller test. (5)

Consider the results in Table One below where the Granger causality test has been applied to two stationary series denoted as REG1 and REG2 respectively. Operating at the 5% level of significance, the results indicate unidirectional causality running from ____ to ____. (4,4)

Table One Null Hypothesis: Obs F-Statistic Prob. REG1 does not

Granger Cause REG2116 0.88765 0.4922 REG2 does not

Granger Cause REG13.34567 0.0076 - When applying an even length moving average smoother to quarterly or monthly data to obtain a trend-cycle, a problem arises in that the calculated moving average falls ____ time periods. (7)

- Ericsson (2008) used forecasts of oil prices and changes in oil prices to illustrate a lack of robustness associated with the ____ statistic. (4)

Down

Table Two presents results obtained from application of the Engle-Granger procedure to regional house price indices (in natural logarithmic form) for the Outer South East (OSE) and West Midlands (WM) regions of the UK. Operating at conventionally considered levels of significance, these results do not provide evidence of the series being ____. (12).

Table Two Dependent tau-statistic Prob. OSE −1.863635 0.5998 WM −1.900103 0.5814 - ____ loss is created by a monopolist producing lower output and charging a higher price. (10)

- Under the ____ forecasting method, the forecast of a variable for the next period is its current actual value. (5)

- The theory of comparative advantage is typically associated with which economist? (7)

- The Chong- ____ test is a test for forecast encompassing. (6)

- The Holden-Peel test has a null of no forecast ____. (4)

For those interested, here’s the completed crossword:

| C | D | |||||||||||

| N | S | M | O | O | T | H | N | E | S | S | ||

| A | I | A | ||||||||||

| I | N | D | ||||||||||

| V | T | P | O | W | E | R | ||||||

| R | E | G | 2 | R | E | G | 1 | E | I | |||

| G | I | C | ||||||||||

| R | G | A | ||||||||||

| A | H | H | R | |||||||||

| T | E | T | D | |||||||||

| B | E | T | W | E | E | N | O | |||||

| I | D | D | ||||||||||

| A | R | |||||||||||

| M | S | F | E | Y |

In our example, to illustrate how we can adapt material to cover any topic, we’ve thrown in a combination of econometrics and economic theory. Let’s now pick up on pedagogical considerations in our design. For examples of behavioural activity, see clues such as [2 down] or [8 down]. These essentially ask for definitions to be completed, requiring no in-depth analysis or consultation of additional material. However, they can also be used as ice breakers. For example, after gently reintroducing monopoly with [2 down], there might be a shift to pluralist discussion into alternative approaches such as cost-plus pricing in post-Keynesianism. Similarly, for [8 down], empirical output associated with application of the Chong-Hendry test can be introduced to consider testing equations, test statistics, inferences, properties of forecasts, and the relationship between forecast encompassing and forecast combination. [9 across] is another example as we can move from completing the statement to then explore the use of centred smoothers as solution to the problem identified with a requirement to demonstrate understanding by calculating 2 x 4 MA (2 x 12 MA) examples using specific quarterly (monthly) data provided.

Other clues provided are deliberately more ‘cognitive’ in their nature, as illustrated by [7 across] and [1 down]. Here, an understanding of the topics of causality and cointegration is not only required but has to be applied to answer the clues. Transferable knowledge therefore comes into play.

So what?

We have sought to bring to your attention the use of crosswords as a learning tool in Economics. They are evidently useful for ‘recap and revise’ sessions. But make sure that you go deeper, ensuring that you embed their application within active learning methods that embrace both behavioural and cognitive activities. While cognitive activity should always be included to generate meaningful learning, ‘mixing and matching’ is recommended to give a more comprehensive experience which incorporates more straightforward exercises along with requirements to synthesise information and use higher-order skills. Flexibility is warranted and possible. In short, in the case of recapping, you may not necessarily want to kick off with something complicated on a topic covered 8 weeks previously. However, the suppleness of crosswords readily allows cognitive activity to voice ‘show me you know about this topic not by repeating an explanation or definition, but applying your knowledge to solve a specific problem’ requirements.

The approach avoids superficial time-filling and can be developed in line with your own pedagogical preferences and objectives. Consider, for example, the idea of ‘team-based learning’. Exercises can be constructed where answers to different clues are compatible: Group 1 does [down]; Group 2 does [across]; they then see if the solutions fit. Alternatively, it can be used for reading beyond the textbook (RBT). Here, students can be directed to specific papers, or elements within those papers, to solve a particular clue. [5 across] and [10 across] provide examples of this approach within our illustrative crossword.

Get crosswording!

References

Bonwell, C. and Eison, J. 1991. Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. Washington DC: George Washington University.

Cook, S., Watson, D. and Vougas, D. 2019. Solving the quantitative skills gap: a flexible learning call to arms! Higher Education Pedagogies 4, 17-3 https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1564880

Crawford, C. 1925. Some experimental studies of the results of college note-taking. Journal of Educational Research 12, 379-386. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1925.10879612

Long, A. and Lock, B. 2014. Lectures and large groups. In Understanding Medical Education, Swanwick, T. (ed.), pp.137-148.

MacManaway, L. 1970. Teaching methods in higher education- innovation and research. Universities Quarterly 24, 321-329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.1970.tb00346.x

Mayer, R. 2021. Multimedia Learning (3rd edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Patrick, S., Vishwakarma, K., Giri, V., Datta D, Kumawat, P., Singh, P. and Matreja P. 2018. The usefulness of crossword puzzle as a self-learning tool in pharmacology. Journal of Advances in Medical Education and Professionalism 6, 181-185. PMID: 30349830

Prince, M. 2004. Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education 93, 223-231. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

Proud, S. 2022. If you build it, will they come? A review of the evidence of barriers for active learning in university education. REIRE Revista d'Innovació i Recerca en Educació 15, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1344/reire.38120

Webb, R., Watson, D., Shepherd, C. and Cook, S. 2021. Flipping the classroom: is it the type of flipping that adds value? Studies in Higher Education 46, 1649-1663. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1698535

↑ Top