Andreas Markoulakis

Department of Economics, University of Warwick

andreas.markoulakis at warwick.ac.uk

Published March 2025

1. Introduction

During the academic year 2023-2024, I participated in setting up a teaching intervention in economics for small group sessions at the University of Warwick. Below, I describe how this intervention was implemented and some initial results but first, I want to explain why this type of intervention was chosen.

The intervention I employed was the One Minute Paper (OMP), a technique apparently introduced by Charles Schwartz in early 1980s. This is a classroom assessment technique at the end of seminars where students answer a couple of questions on the material just discussed. OMP enables lecturers not only to engage the students but also to collect valuable feedback about their learning and their understanding. This is the main reason why I decided to use this technique, to collect feedback from my students beyond what is mentioned in module evaluation, which is not always informative for the instructors and anyway typically only produces feedback at the end of a module.

Another reason I opted for this technique is because it presents an opportunity for students to inform the tutor of things they might not understand. This can be especially useful for students who are shy, who have not good command of English or for foreign students, who hesitate to ask questions (Cheng, 2000; Stead, 2005). Importantly, by using this technique, I wanted to show to my students that I value their opinion, and I care about what they learn and what they think about the seminars. My overall impression is that students perceived OMP favourably, they answered the questions and offered positive comments.

Finally, given that there is some evidence in the literature that OMP has a positive impact on students’ knowledge in economics (see Chizmar and Ostrosky (1998) and Das (2010)), this prompted me to use it to explore its effectiveness.

2. The intervention

Below I explain the OMP teaching intervention I adopted. At the end of a seminar class (small group teaching), students were asked to answer two questions, the first summarizing what they have learned and the second on comprehension, if they have a question. A paper-and-pencil approach was used to distribute the OMP questions to the students. I have opted for a paper-and-pencil approach since it can have a better response rate than an online survey (Dommeyer et al., 2004) and ultimately this can lead to a higher sample size.

The OMP was adopted during the seminars for the module EC138 (Introduction to Environmental Economics) for 1st year students. This module has 4 seminars, delivered every second week.

There were two pairs of questions, the first set asked during seminars 1 and 3 (denoted S1, S3) and the second pair during seminars 2 and 4 (S2, S4). The exact OMP questions were as follows:

1st pair (S1, S3):

Q1. What was the most important thing you learned in the seminar today?

Q2. What question (if any) remains unanswered?

2nd pair (S2, S4):

Q1. Here is one thing I don’t understand well, and I am hesitant to ask about it.

Q2. If you had to offer a summary for today’s seminar using a couple phrases, what would it be?

The two different pairs of questions have been used so that students do not get bored and in addition to see how their answers could be altered if the framing of the questions changes. This is particularly important for the questions on comprehension where I specifically examine if some students might be hesitant to ask questions. I explicitly use this format to control for potentially shy and international students who might hesitate more.

I would say that framing is less relevant for the two questions on summarization, and I was not anticipating any differences, but still as shown below, the latter version allows for comments by the students.

3. Some findings

3.1 The impact of framing

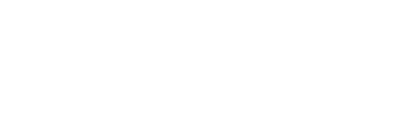

I start the analysis of the results by focusing on the questions on comprehension (Q2 and Q1 respectively in the two sets). The numbers of the students who answered “None” or “N/A” are shown in the graph below. These are the number of questions in each seminar where the students answered “None-N/A” on which questions remained unanswered (S1, S3) and what has not been understood and are hesitant to ask about (S2, S4).

I would like to stress two things here. First, there are noticeable similarities in answers between seminars 1 & 3 and seminars 2 & 4 (remember each pair of seminar asks the same question, so they can be compared). In either case, slightly more than 70% of the students reported no unanswered questions.

Second, when the question explicitly asks about things that students are hesitant to ask about, then the number of “None” decline considerably and could reach as low as 1 in 4 students (25%). So, the conclusion here is that when being hesitant to ask questions is mentioned explicitly, the level of comprehension seems to drop. It is unclear why this decline is happening, perhaps it has to do with students who are shy to ask questions, or foreign students who don’t have good command of the English language or even students who are reluctant to participate in the class and answer the questions. Unfortunately, this is a difficult point to address. Still, such a result I think should be a source of concern for the module tutor.

Fig. 1: “None/NA” answers in comprehension questions

3.2 Answers on summarization

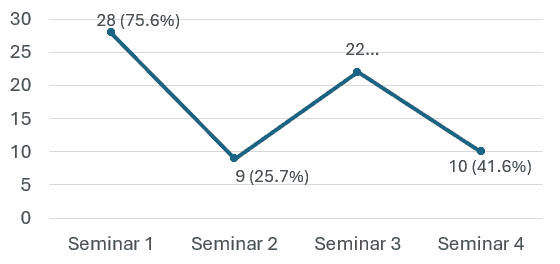

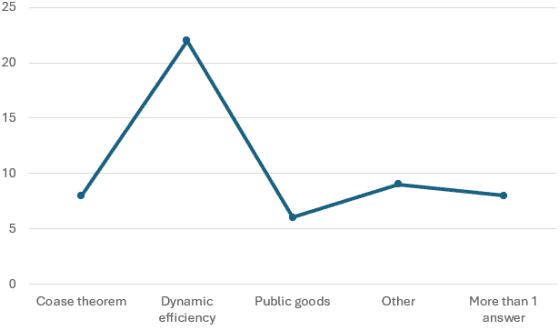

Beyond understanding, the other question of the OMP was on summarizing what was learned or the most important things learned. There was no specific expectation on the results here, I was just aiming for students to reflect on the seminar and to write down the most important things learned. In the two figures below, I summarize the pattern of the answers for seminars 1 and 3 (for the other two seminars, the patterns were similar). As one can see in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, most of the students summarized the material in a few important concepts taught, showing that students were indeed reflecting properly on the taught material (Fishman and Wahesh, 2020). Although I admit that this type of summarization has obvious limitations and can lead to overarching simplification (Stead, 2005), it is still useful for students for long-term retention purposes and might help them prepare better in the exams (Lang, 2021).

Fig. 2: Answers pattern in Q1, Seminar 1

Fig. 3: Answers pattern in Q1, Seminar 3

3.3 Positive comments

When viewing the answers of the students, I was pleasantly surprised to see some positive comments by students about the workshop. This was especially true for seminars 2 and 4 and, apparently, it is related to how the questions on summarizing the seminar material were put forward: it seems to be more likely students offer positive comments when they are asked to “offer a summary for today’s seminar” than when asked “what was the most important thing you learned in the seminar today”. Below (Fig. 4), you can see some of these comments.

Fig. 4: Positive comments by students

“Improved my understandings of the graphs.”

“Informative and well-structured.”

“Incisive and useful.”

“Thorough explanation for each exercise.”

“Detailed explanations with visuals.”

“Cap and trade graph, informative and challenging.”

“Discussing biodiversity using lots of reports, help me to understand the ideas in depth.”

“Very interesting, especially about the themes in question.”

“Informative and good.”

“Very insightful.”

“Comprehensive and detailed.”

“Informative, helpful analysis of diagrams on biodiversity.”

3.4 Frustrated comments

Of course, along with the positive comments, one should also expect some less positive ones, I would call them frustrated comments on behalf of the students. Although there were only a couple of such comments (shown in Fig. 5), they demonstrate the same thing: that students have fallen behind in their studying, not that they don’t understand what they are being taught, perhaps because these comments are from the last seminar in the final week of the term. In any case, these students are apparently honest with the lecturer (Almer et al. 1998), so I don’t view this as a negative for the teaching practice.

Fig. 5: Frustrated comments

“I am not following the contents of the lectures on offsetting, not really understanding the lectures.”

“Need to revise exactly what offsets are about.”

3.5 Some extensions

Given the above findings, the obvious question would be to examine further why this discrepancy in framing has arisen. This is not an easy task and needs further data to be answered. At this point, the only thing I could examine is if the status of the students, that is, being from the UK, EU, or Overseas, could be related to being more hesitant to ask questions. It is my intention to find the relevant data and examine this question further.

It is possible to expand the above analysis by having a closer look at the potential connection between the assessment marks (final exams marks and the marks of the other assessments for this module, a group presentation and group policy brief) and the answers students offer in the OMP. This can allow a close examination of OMP impact, particularly at individual level for each student since at group level we introduce noise, and this could invalidate any findings.

To extend the discussion here, it might not be unlikely to anticipate that students who reported no answered questions on comprehension will receive higher marks in the exams and the assessments.

4. Concluding remarks

Obviously, the main limitation in the analysis described above is the relatively limited data, since this module had around 50 students. In the future, it is my intention to analyze more data and see if the patterns described above continue.

Other future interventions using the OMP are also possible, like the use of OMP for specific groups only (say, only for a subgroup of students) to better determine its effectiveness. It might be interesting to examine more deeply the understanding of students after each seminar or even to examine what the students retrieve from seminars after some time, this can allow to examine learning for long-term retention and perhaps understand better students’ learning (Lang, 2021).

All these are some interesting questions to consider which seem to have attracted little attention in the literature in teaching economics modules.

References

Almer, E. D., Jones, K., & Moeckel, C. L. (1998). The Impact of One-Minute Papers on Learning an Introductory Accounting Course. Issues in Accounting Education, 13(3).

Cheng, X. (2000). Asian students' reticence revisited. System, 28(3), 435-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(00)00015-4

Chizmar, J. F., Ostrosky, A. L. (1998). The one-minute paper: some empirical findings. Journal of Economic Education, 29 (1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/1182961

Das, A. (2010). Econometric assessment of “One-Minute” paper as a pedagogical tool. International Education Studies, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v3n1p17

Dommeyer, C. J., Baum, P., Hanna, R. W., & Chapman, K. S. (2004). Gathering faculty teaching evaluations by in‐class and online surveys: their effects on response rates and evaluations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(5), 611-623. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930410001689171

Fishman, S. M., & Wahesh, E. (2020). The F3: Faculty Feedback Forms for Students. College Teaching, 69(2), 61–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2020.1814685

Lang, J. M. (2021). Small Teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning, 2nd Edition, Jossey-Bass.

Stead, D. R. (2005). A review of the one-minute paper. Active Learning in Higher Education, 6(2), 118-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787405054237

↑ Top