The Economics of Joyful Learning: Designing Spaces for Innovation and Impact

Dr Rabeya Khatoon NTF, SFHEA, Associate Professor, School of Economics, University of Bristol

Published October 2025

Purpose

What makes you enjoy something? I’d say it’s your presence in whatever you are doing. As an educator, you’d like your students to attend the sessions you offer, to listen to what you say, and to learn in the way you expect them to learn. Isn’t it true from the student’s perspective too? They would obviously enjoy the lesson if the educator values them as individuals and teach in the way they’d expect them to teach. As an educator in higher education, how would you reach to the equilibrium point to ensure everyone’s presence to the learning space? I am sure, many educators now know- it’s the authentic, active learning and belonging that does the job.

To make it realistic, imagine a classroom with diverse students; diverse in multiple ways – visible (e.g., nationality, race, gender) and invisible (e.g., personality types, subject background if studying for postgraduate or joint honours degrees) diversity. Recent financial pressures on universities mean even larger undergraduate cohorts, and a desperation for international students in postgraduate. That makes the mix challenging for the educator- how would one know all students in such large ‘small-group’ tutorials, or establish connections among the diverse group of students? What if some of the students are ‘quiet’, for example because of their language barrier (Khatoon and Spencer, 2022)?

Trials

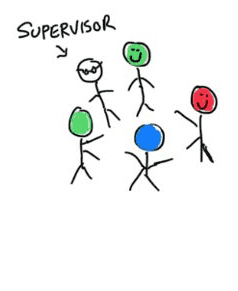

I tried a live quiz- it creates fun activity, but no belonging. I gradually moved towards ‘pub quiz’ style reading quizzes, encouraging group discussion before response. I have seen students getting up from where they were sitting to go to people who look ‘similar’ to them to form groups. That helps with belonging, and makes it easier for me to learn their names (clustering as a cognitive strategy) improving ‘presence’. However, it lacks the curiosity spark ("Why do I do what I do?") that is supposed to foster knowledge creation- one of the objectives of higher education.

Figure 1: Grouping that allows self-selection could lead to homogenous groups.

The What

I enjoy problem-solving and applying my learning in real-world settings. When the opportunity came, I designed an interdisciplinary MSc program, Economics with Data Science (EwDS), where I introduced group (of 3 to 5 students, the magic number) dissertations with industry projects. A very ambitious one-third of the MSc depends on teamwork (that comes with free-riding challenges) and industry collaboration. The interdisciplinary nature of the program means that there is something new for me to learn, and also for my students as I am maximizing the (invisible) disciplinary diversity. The industry collaboration gives everyone a purpose for doing what they do- for real world impact, and at the same time accelerates student employability. The group work, when successful, should contribute to belonging and provide a fresh, curious perspective that embraces diversity. The model should be manageable to run with large numbers of students as each group will need one academic supervisor and one report for the supervisor to mark. The industry partners receive a free consultancy, an insider look of students’ preparation, and greater exposure.

So what?

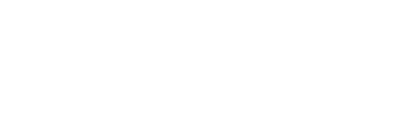

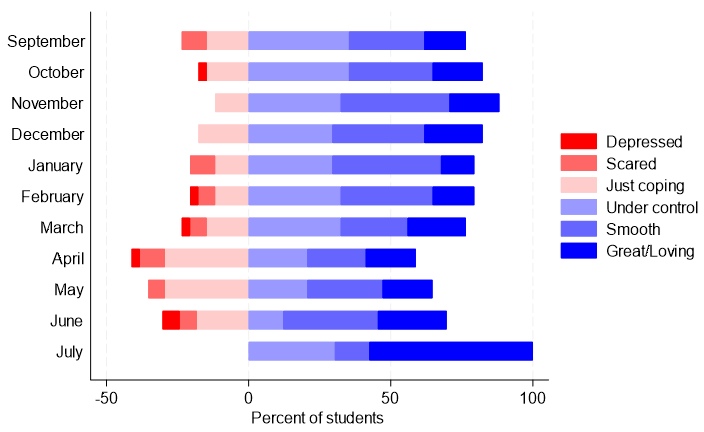

The program has been successfully running since 2023/24, with an impressive student success rate (100% graduation of the first two cohorts). Graphs 1 and 2 give a glimpse of the first cohort’s story. An emotional mapping exercise (Evans, 2015) reported in graph 1 showed that students’ feelings toward teamwork evolved positively over time. Early anxiety gave way to confidence and even enjoyment by the end of the programme, illustrating the transformative effect of structured collaboration. Graph 2 shows a comparative picture of marks achieved in different points in the year including my teaching in AFE (same for both groups), with a clear upward trajectory for the MSc EwDS students. Despite starting with lower average pre-sessional scores, MSc EwDS students achieved 12.5% higher dissertation marks than their peers in MSc Economics and Finance. Within MSc EwDS, the highest marks in the dissertation have been achieved by the most diverse groups over the last couple of years. Some graduates already started their doctoral and pre-doctoral studies; some went for great industry jobs including Bank of China, Lenovo, Jane Street, Siemens, and so on. And we received some wonderful feedback from the participating companies.

Graph 1: Emotional sketch of teamwork, MSc EwDS students (N=39) 2023/24

Graph 2: Comparative assessment performance of MSc EwDS (N=39) and MSc Economics and Finance (N=55) students 2023/24.

The green boxes are for units both designed and taught by me.

The How

What made the initiative successful and helped tackle free-riding? Group work succeeds when it is carefully structured. MSc EwDS dissertation structure draws on economics literature showing that repeated interactions and mutual monitoring enhance cooperation through relational contracts (Fahn & Hakenes, 2019). Using the logic of repeated games (Farrel & Maskin, 1989), students stay in the same teams for multiple exercises, building trust and accountability.

The dissertation module explicitly embeds teamwork into its learning outcomes and unfolds over three distinct phases between January and August:

- Collaborative Data Work (Weeks 13–24):

Students collect and process data in supervised lab sessions, submit a formative report, and deliver an informal presentation to peers. This early phase encourages experimentation without grade pressure, but is incentivized being a pass/fail element. - Industry Showcase:

Students present preliminary findings to partners and supervisors in a supportive, celebratory environment that strengthens communication and confidence. This part contributes to 20% individual marks, but with less pressure, as the students are not expected to have the final output yet. - Equity-Based Assessment:

The third phase is writing up of the group report, where the group mark translates to individual marks taking into account individual students’ equity share (Adams, 1963) - the individual contribution to teamwork.

Engagement is tracked through teamwork monitoring software such as FeedbackFruits, allowing students to provide confidential weekly feedback on team participation. These data remain formative until final “equity shares” are collectively agreed, ensuring fairness and transparency.

Figure 2: Repeated interactions in a meaningful way to establish relational contract

| Stage 1: Team-building exercise | Stage 2: Informal presentation | Stage 3: Gradual cooperation | Stage 4: Strong collaboration; Relational contact |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

Preparation

Behind the success of the dissertation, there are some key preparation elements that helped break some of the barriers of engagement that often result from diversity. In their first term core module, jointly designed by me and a couple of my engineering colleagues, they start with formative teamwork in the way they prefer to be grouped, e.g., with peers that look alike to them. By introducing active flipping of a lecture with group presentation of (advanced) academic literature, I managed to provide them an accelerated content in an intellectually stimulating way - basically giving them the flexibility to learn in the way they wish to learn. This formative, flipped exercise received a 100% engagement in the past couple of cohorts. The focus on early relationship-building cultivates psychological safety (Edmondson, 2018), encouraging students to ask questions, take risks, and engage deeply with quantitative material.

In the second term, the preparation highlights include fun teambuilding exercises and reflective sessions on personality traits and action learning, providing space for them to engage within their dissertation team. The dissertation grouping doesn’t allow them to group as they like, and isn’t a random grouping as well. We group them carefully by taking into account their preferences, their first term performance, and any contextual factors to maximize the chances of balanced groups.

Final words

Before I finish with a short week-by-week implementation guide, I’d like to acknowledge that the success of the group dissertation with industry projects wouldn’t have been possible without the dedicated work of the Professional Liaison Network and the program director, who worked hard to secure 13 industry projects covering the first couple of years of the program. I also would like to assure that the lack of individual research doesn’t undermine student preparation for doctoral studies or a future in academia if they wish to, as the dissertations are, in effect, of much better quality than what an individual can achieve given the timeline. However, success depends not just on assessment reform but on early teamwork education, relational learning, and coaching-based pedagogy - key to developing what Olivier (2014) describes as self-defining graduates who enhance both the economy and society.

Ultimately, teaching economics should go beyond producing efficient markets of ideas. It should cultivate inclusive communities of inquiry where students from diverse backgrounds collaborate to generate insights that matter - to themselves, to employers, and to the world.

Implementation Guide: Dissertation Timeline

| Week | Focus | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | Dissertation formalities | Library, ethics, introducing collaborative workspace and monitoring software |

| 14 | Ethics of AI/Machine Learning, Data Sources | Algorithmic bias, Data sourcing |

| 15 | Data visualisation | Data storytelling and design |

| 16 | Teambuilding | Personality mapping, action learning sets |

| 17–22 | TA-supported labs | Weekly progress and engagement tracking |

| 23 | Peer presentations | Informal showcase of lab reports |

| 24 | Lab report submission | Pass/fail formative component |

| May-June | Group dissertation work | Teamwork under academic supervision |

| July | Presentation showcase event | Summative presentation of work-in-progress |

| August | Writing up | Teamwork under academic supervision |

References

Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 67(5), 422. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040968

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. OCLC 1047524808

Evans, C. (2015). Exploring students’ emotions and emotional regulation of feedback in the context of learning to teach. In V. Donche, S. De Maeyer, D. Gijbels, and H. van den Bergh (Eds.) (2015). Methodological challenges in research on student learning (pp. 107-160). Garant: Antwerpen.

Fahn, M., & Hakenes, H. (2019). Teamwork as a self-disciplining device. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 11(4), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.20160217

Farrell, J., & Maskin, E. (1989). Renegotiation in repeated games. Games and economic behavior, 1(4), 327-360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0899-8256(89)90021-3

Khatoon and Spencer (2022). Exploring barriers to accessing academic advising and tutoring in PGT students: Using machine learning and qualitative interviews, work-in-progress, University of Bristol.

Olivier, S. (2014). The employability agenda and beyond: what are universities for? Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

↑ Top