Moving Multiple-Choice Tests Online: Challenges and Considerations

Stefania Paredes Fuentes

University of Warwick

Written August 2020 for the Virtual Symposium on Adaptable Assessment Published as a case study October 2020

Any assessment taking place after March 2020 had to be

moved online and student sat them remotely. Assessments had to be redesigned in light of this new scenario and we are going to be in a similar situation next academic year. This article describes my experience in redesigning a MCQ test for a Macroeconomics module.

The experience this year helped me to become more confident in using summative online Multiple-Choice Question (MCQ) tests in the future, even after we will be able to meet face-to-face. The main challenge presented by MCQ tests is the time required to design good questions. In this article I explain some of the main considerations I made when writing the questions with a practical example.

I start by briefly providing the context of the assessment before the COVID19 scenario. Section 2 describes the changes made when shifting it online and explains some of the considerations to take into account when redesigning the assessment. Finally, given the concerns about academic integrity with online assessments, in Section 3 I discuss how assessment design can help to mitigate poor academic practice and provide some evidence based on this year experience that may help to lessen these concerns.

1. General context and assessment structure

This assessment is for Macroeconomics I, a core module for BSc Economics students in Year 1. There are around 360 students in this module. Lectures run for the whole year and are delivered by two lecturers (I teach in Term 2). This test is worth 10% of the final mark and it assesses Term 2 content. The rest of the mark is given by various other assessments including another MCQ test in Term 1, two group assessments and a final exam. The MCQ test had to be sat after the Easter break under invigilated conditions and to be completed in 50 minutes.

After the March 2020 events, this test was moved online, and the final exam was cancelled. In order to pass the module, students had to pass the assessed components. The test has 10 questions (one mark each) with four choices of which one or more can be correct. A question is awarded marks only if all correct answers are selected (zero otherwise). There is no negative marking. This structure was maintained in the online setting.

2. Considerations and challenges with the assessment design

Multiple Choice tests are commonly used as low-stake assessments to keep students engaged with the subject. Questions tend to require students to recall information or remember some basic concepts from the module. However, this is not necessarily good practice (not even for invigilated tests), and we can design questions that require more than just remembering concepts that could be easily found in the textbook, lecture notes or by using search engines.

Online/remote tests are open book, so we need to avoid questions that merely required students to recall basic information and/or remembering concepts or facts which could be easily found in the textbook, lecture notes or by using search engines (e.g. “what is the correct equation for the Phillips Curve?”). However, designing MCQs that test higher-order learning[note 1] require a greater time-investment.

At the time the university announced all assessments to be moved online, I had not prepared the test yet. This was actually positive, as I did not try to adapt a test initially thought for sitting in a classroom under invigilation, but I focus directly on designing an online test. First, I consider the objective of this test. The original purpose of this assessment was to promote engagement with Term 2 material and help students to understand any gap in their knowledge, in preparation for the final exam. Under the new scenario and the cancellation of the final exam, this became the last opportunity for students to demonstrate their engagement with Term 2 material. There was a good level of activity on the online forum for the module where students could ask clarification and further explanation.

It is important that the assessment does not add extra-challenges unrelated to the subject, so the outcome reflects students’ real academic attainment. This has to always be the case, but the change in conditions after March 2020, made this even more important. To minimise disruption for students due to the change in conditions, I consider the following:

- Familiarity with the type of scenario presented: I looked at the lecture notes, problem sets, and MCQ practice tests available on Moodle to make sure all students had the opportunity to engage with similar questions to the ones in the test;

- Time available to solve the problems: If mathematical calculations were required, I estimated the time available for each question;

- Use vocabulary that have been used during the course: Avoid adding new terminology and stick to what it has been used during the lectures and in the textbook;

- Mixed questions on various topics: I divided the material in topics, and there was at least one question on each topic. It may be easy to write more questions on topics that require more calculations as it makes easier to write MCQ, but good students will revise the full syllabus, and it is only fair if they have the opportunity to demonstrate their engagement.

- Same level of difficulty in different versions of the questions: there were various versions of the same question (more on this below), and it is important that all versions had a very similar level of difficulty;

- Clear communication on the changes introduced: Students were familiar with the previous test, so it was important to let them know the changes introduced. I also let them know about the question design. I told them that the questions would be designed keeping in mind that they would have had access to the course resources, that there were different versions of the same questions.

- Familiarity with the technology: Given that we used a new system for this test (Questionmark), I sent students a mock test before the real test took place, for them to familiarise with the software (around 50% of students tried the mock test).

To notice that points 1-4 are good practice for any assessment and not only online ones, while points 5-7 are more specific to the current scenario.

In order to design the questions trying to go beyond pure recall/remember learning and try to test higher-order learning skills, I found Scully (2017)’s recommendations very useful. In particular:

- Rather than asking to select the correct concept definition, present students with a specific instance and ask them to identify the underlying rule or concept so that the student need to have a good understanding of the alternative concepts proposed in the list of choices.

- Avoid highly implausible alternatives. Even the weakest students will be able to rule these out, which means that students do not engage in higher level thinking when choosing the correct answers. Of course, it is very important to avoid introducing subjectivity. The correct answer(s) must remain indisputably and objectively the “most correct” ones.

- Ask questions that require students to make interconnections between different knowledge to arrive to the correct answer. However, we need to make sure that in trying to make students to combine concepts and ideas, we maintain clarity of wording.

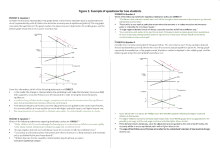

Figure 1: Example of questions for two students

Figure 1 shows an example of two of the questions in the test.[note 2] Most of the questions required students to make calculations, interpret either a theoretical scenario described by graphs, or a real one described by an excerpt of the Financial Times. Question 1 in the left panel requires students to understand how a positive demand shock affects the labour market and how policy makers respond to the shock (in green the correct answers). Following Schully, I aimed for the incorrect options to be highly implausible only if students clearly understand the basics of the model. To rule out one answer, students need to know that the MR curve does not shift with demand shocks, and to rule out the other, a good understanding of the difference between a temporary and permanent demand shock and their effects on the economy is required. Of course, the book and lecture notes do explain the effects of positive demand shock, but it would require looking for the specific concepts (they are in more than one chapter) and spend valuable time.

Similarly, none of the incorrect answers for Question 7 in the left panel are highly implausible: a large negative demand shock can lead to deflation but this is not always the case; monetary policy is the preferred stabilisation policy tool, but this does not mean that fiscal policy is not used; and inflation bias can also be caused by the government trying to push unemployment below its equilibrium level.

Questions that go beyond recall and remembering in an online setting also help to address other issues. For instance, it may help to identify students’ achievement of the learning outcomes, differentiate students’ achievements and identify progress. Importantly, it also helps to maintain the credibility of the assessment, as if students perceive it to be “too easy” they may not put enough effort in preparing for the test.

3. Poor academic practice: Some evidence

Good assessment design also helps to address one of the main concerns for lecturers: integrity of the assessment.[note 3] Answers to questions that go beyond recalling information are more difficult to copy directly from books or communication with other students. In addition, the software used allowed to introduce some extra deterrents such as:

- Each question had more than one version, limiting the likelihood of students sitting the exam same test. The correct answers per version also changed;

- Questions were presented to students one by one in random order (e.g. question 1 for Student A was question 7 for Student B);

- Choices within each question were presented in a random order.

In Figure 1 I try to replicate the scenario for two different hypothetical students. The left-panel shows the test for Student A, the right panel for Student B. Both students had a question describing a positive demand shock scenario, but these were presented in different order: for Student A this is Question 1, for Student B this becomes Question 9. They also see different versions of the same question with different potential answers. Similarly, Question 7 for Student A is Question 2 for student B, and the different versions had different number of correct answers.

Table 1: MCQ results comparison

| Test 2 (online) | Test 1a (invigilated) | MCQ 1b practice (online) | MCQ 2c practice (online) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | +6 | –11 | –16.5 | |

| Median | +4 | –6 | –16 | |

| % pass (40+) | 85% | 97% | 73% | 65% |

| % first | 24.5% | 46.2% | 19% | 11% |

| engagement | 97% | 99.5% | 62% | 65% |

Notes:

a–Test 1 was based on the first part of the module

b, c-Marks for the first attempt (students could attempt the test as many times as they wished)

It is difficult to say how many students cheated in the test, but I have little evidence that more students engaged into poor academic practice or that they benefitted from cheating. If this were the case, we would expect to see a high average mark and a distribution skewed towards the right. Table 1 shows some basic stats for this Test, and a comparison with Test 1 (sat under invigilation in December) and two optional MCQ tests available on the Virtual Learning Environment.[note 4] We observe that the average and median mark for Test 2 were 6 and 4 percentage points lower respectively, compared to Test 1 (invigilated) and more students failed Test 2 than Test 1 (15% vs 3%). This may indicate that we should be more worried about potential negative effects of the scenario under which students sat the test, rather than about cheating. However, we have not much evidence of a large negative effect of the online setting either. As mentioned, we offered students with a mock test to help them to familiarise with the software (around 50% of students used this), and I used the same software for MCQ tests used in other modules. Also, 97% of students sat the test (class size ~360 students), and many of those who did not sat the test had mitigating circumstances.

One explanation for the lower performance may be found in the topics covered in the two terms. The material covered in Test 1 is more introductory and similar to A-level Economics.[note 5] The difficulty of Test 2 was more in line with the optional practice tests available in the learning environment.[note 6] If compared to these tests, Test 2 had a higher average mark and more students passed and achieved a first (see Table 1, last two columns). In general, the mark distribution was in line with other modules, and with the general expectations for the course.[note 7]

4. Final considerations and conclusions

The new academic year will bring a new series of challenges as we are going to be facing a scenario that is new for many of us. However, there are lessons we can learn from the recent experience which can help us in the transition to online/blended teaching and learning.

My experience with online Multiple Choice taught me some lessons on assessment design. Good assessment design can help to assess higher-order skills beyond remembering or recalling basic knowledge, contribute to create assessments that help students to engage with the subject, and mitigate poor academic practice.

Good communication with students is essential. Students need to know the structure of the assessment, but also how the questions are designed (e.g. taking into account an open book scenario). Mock tests are useful to familiarise students with the technology and the questions.

Despite all our efforts, we cannot completely avoid students engaging in poor academic practice (i.e. cheating). However, I do not think this should be our main concern. Multiple choice tests should be part of an assessment strategy that include various forms of assessment in which students have many opportunities to demonstrate their engagement with the learning outcomes of the module and understand the benefits of engaging with the assessments to build up knowledge and understanding. This should also help to deter poor academic practice, as students see the benefits of engaging with each assessment.

Notes

1. Higher-order thinking is linked to Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom et al. 1956, revised by Anderson et al. 2001) and refers to the cognitive processes a learner may engage. The most basic level is “Remembering” while higher levels refer to “understanding”, “applying”, “analysing”, “evaluating” and “creating” (Krathwohl, 2002).

2. The objective to show these questions is not to argue these are “good” multiple choice as I am sure these can be improved, and more experience will help me with this. The objective is to share my experience on moving beyond “recall” questions, and the reasoning behind the design of these questions.

3. These concerns are intensified when students are sitting the assessments remotely, despite no clear evidence that cheating in more common in online tests than in face-to-face. I talked more about this in here: https://www.economicsnetwork.ac.uk/showcase/fuentes_assessment (joint with Tim Burnett). See also Harmon, Lambrinos & Buffolino (2010).

4. This was the first-time students were scheduled to sit a second test, so it is not possible to compare with past cohorts.

5. This is not a requirement for this degree, but 70% of students have an A-level (or equivalent) in Economics.

6. The practice tests were made available during Term 2 (January –March) and many students completed these tests during term. Students had the full Easter break for revision (Test 2 took place in Term 3).

7. Despite this, I cannot say for certain that students did not find ways to cheat, but this is difficult to understand for invigilated tests too. We use various large lecture theatres (capacity 300-500 people) during the test and try to sit students 2-3 sits apart. There are 2 or 3 invigilators per room and there are usually two versions of the test too. Despite this, we cannot assure that no communication happens in the lecture theatre. The evidence suggests that cheating in invigilated exams is higher than what we want to admit or gets reported. See Burnett (2020), and Bushweller (1999), Dick et al. (2003).

References

Burnett, T. (2020) “Understanding and developing implementable best practice in the design of academic integrity policies for international students studying in the UK”, Technical report, UK Council for International Student Affairs.

Bushweller, K. (1999) “Generation of Cheaters”, The American School Board Journal, 186 (4), pp. 24-32.

Dick, M., Sheard, J., Bareiss, C., Carter, J., Joyce, D., Harding, T., & Laxer, C. (2003) “Addressing Student Cheating: Definitions and Solutions”, ACM SIGCSE Bulletin, 35 (2), 172-184. https://doi.org/10.1145/782941.783000

Harmon, O. R.; Lambrinos, J.; Buffolino, J. (2010) “Assessment Design and Cheating Risk in Online Instruction”, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 13 (3)

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002) “A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview”, Theory into Practice, 41 (4): 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Scully, D. (2017) “Constructing Multiple-Choice Items to Measure Higher-Order Thinking”. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Vol 22 (4). https://doi.org/10.7275/ca7y-mm27

↑ Top