Tim Burnett and Stefania Paredes Fuentes, University of Warwick

Written March 2020

Published by the Economics Network June 2020

In Summer 2020 the Economics Network ran a Virtual Symposium which produced case studies and resources about online assessment and other topics. Follow the link for details.

Abstract

Under the current scenario, university lecturers need to rethink their assessment strategy. Many will need to shift from closed-books, time-limited examinations, to remote assessments. The choice of remote assessment should not be an after-thought as it may define our response to the current crisis and will affect Universities’ academic standards. Students’ performance, marks and final degree classification depend on assessment and we owe to set up fair assessments in line with learning outcomes. We offer a five-step guide on how to change assessments and discuss six alternatives. For each alternative we discuss their potential advantages and disadvantages for students’ learning and engagement, but also adoption and organisational procedures. Finally, given that students engaging academic malpractice (i.e. cheating) is one of the most common concerns regarding any sort of remote assessment, we explain how good assessment design can help to mitigate some of these problems.

1. Introduction

If you are a university lecturer, very likely you have been asked to change/reconsider your final year exam, given the current extraordinary circumstances. If you are an engaged teacher with a diversified portfolio of assessments for your modules, you probably do not need any help doing this and it is likely that you are helping others with their assessments, or even advising your university (in which case you do not need to read this guide, though you may find it useful).

However, if you have less experience with different assessment types (e.g. you are a new lecturer or have been teaching the same material for a long time), you may feel somewhat overwhelmed by the task of rearranging and redesigning your assessments at such short notice. Rest assured, we (and others in the academic community) are here to help! We have been working for a while trying to change our assessments to best reflect students’ learning capabilities, to engage diversity, and promote higher-level of learning. In doing so, things have not always run smoothly; we might have made mistakes, theory and practice could have diverged at points, or it might have taken us time to reach to best solution to a problem. Given this, we hope that by sharing our experiences we might be able to help you (and others) achieve the best outcomes possible in this unprecedented period.

Many of us will be tempted to look for quick solutions; be wary, however, since lack of careful consideration on assessments may negatively affect the perception of the quality of education provided and further disrupt students’ learning. How we respond to this challenge will affect students’ perceptions of their university experience and, given the importance of assessments for students’ progression and degree classification, assessment may have a stronger impact on universities reputation than teaching will.

The rest of this document is structured as follows: first, we provide a guide to the guide which explains what this is about (and what it is not) and how to use it. Section 2 explains where to start in five simple steps and introduces a framework to reflect about any assessment we may set. Section 3 provides six alternatives that you can transition to under the current scenario; we aim to explain the advantages, disadvantages and offer some tips on implementations. Section 4 adds some final remarks on adapting our assessments to these difficult times.

1.1 About this guide

This should not be considered a general guide to setting assessments—this is dealt with in the extensive literature on good and appropriate assessment design. Instead, we have written this as a ‘survival kit’ to help you over this first (significant) hurdle, and, maybe/hopefully, you may be inspired to dig a bit deeper when you design your future assessments.

As an opening proposition, it should be said that assessments should not be an after- thought of the module design, but should be considered as one of the cornerstones of module preparation (What do I want to teach students? How will I test they have learned it? Given these two points, how should I teach?). Understandably, because we are not in the preparation stage, but rather ‘firefighting’, this guide is somewhat working backward: This is what I taught, this is what students have done so far, how can I assess it remotely (i.e. without a sit-down exam)?

Given the timing, this guide will focus on assessments that take place after teaching has finished. As stated, in (too) many cases, these would normally be time-limited exams that students sit in-presentia in university premises. We will avoid any discussion on our profession’s over-reliance on these exams (we reserve the right to do this later!), and simply work on the assumptions that, if you are reading this, you need to find an alternative.

Another important consideration we make is that (most of the) students are not going to be located on campus when taking these assessments. While this is clearly challenging for you, it is also likely to be a new experience for students. Thus, this guide will also be providing advice on minimising the effects of shocks associated with changing the assessment methods.

2. Where to start?

The task ahead of you may appear Herculean, but we would like to assure you that it need not be. The task of remotely assessing students has confronted many academics before us, especially those involved in distance and remote learning. Thus, we have at our disposal a wealth of knowledge and experience which can be applied to the problem at hand.

2.1 Five basic steps

A. DON’T PANIC! Easier said than done but, believe us, this may not take as long as you think. Also, try to avoid being too grumpy because you have been asked to change assessments; while there are many academic tasks that we are asked to do which may not be immediately relevant to our jobs, if you teach a module, you are the best person to set that module’s assessment! You never know, you may gain something from this experience.

B. Consider what assessments students have already done for your module. Ideally, we want to deploy a variety of methods for assessment so that the same students are not always disadvantaged (Knight, 2002). If students have already sat an exam-type assessment (e.g. a time-limited test), another exam may not help to assess your module’s learning outcomes in any case - so you may want to take this opportunity to rethink your overall assessment strategy for future years. Also, read again the final assessment (e.g. exam) that you have already written. As the following sections stress, changing assessment type does not mean throwing away all the work you put into the existing assessment. If you wrote this a while ago chances are you may have forgotten what is in there, so read it again – a fresh look at your content will help you understand what type of revised assessment you might set, and what can be saved.

C. Read university guidelines (if any). This is a very frantic period and many universities are putting in place contingency plans. These will likely give you a good idea of time constraints for your redesign, technologies available, and what support is available to help you. Also, do not worry if you think ‘my university’s guidance isn’t actually helpful’—they may be very busy and/or working on it, and that is why we wrote this.

D. Write a new assessment. Just like that! Not really. This is the hard part and for this reason we dedicate Section 3 to outline the various options available with some hints and tips on transitioning to these assessment types.

E. Provide students with clear guidelines on the new assessment method. Students have been preparing for the assessment you planned. Moreover, if in-presentia examinations are the status quo within your department, then students will be accustomed this form of assessment. Assessment which deviates from the norm may challenge students in more ways than just content knowledge, so you will need to ensure that students are sufficiently briefed.

2.2 Beyond the basics: Understanding the module’s Learning Outcomes

There is one further point to consider before we continue, and it is an important one: Look at your module’s learning outcomes.

This might sound incredibly obvious, routine, or, alternatively, it may sound like completely new and unknown territory for you. You might even think this is not necessary—being that you may never have consciously linked outcomes to assessment previously (this is really common, you are not alone).

Many module leaders are not familiar with their modules’ learning outcomes; indeed, in many cases these have been written by someone else (Head of Teaching, previous lecturer who delivered the module, etc). Often, we, as module leaders, ‘inherit’ modules, and time constraints or competing priorities mean that we continue to reproduce the same material and assessment we inherited.

While, clearly, this is not a great practice, all is not lost! There is no time like the present to familiarise yourself with what your module is aiming to do. Notwithstanding that this might also help you with your teaching in future, understanding what knowledge and/or skills students should acquire for your module is also essential information for the purposes of effectively and efficiently designing your alternative assessment.

2.3 What are we assessing?

Even within the category of remote assessments, there still remains a broad number of possible approaches which can be pursued (as outlined in Section 3). While some types of alternative assignment follow similar principles to conventional sit-down exams, others differ markedly. Each type of assessment is also characterised by its own advantages and disadvantages (you may be surprised to learn that there is not one single type of assessment which dominates others)—these may be in terms of the practicality, or otherwise in terms of the type and depth of knowledge and understanding that alternative approaches can assess.

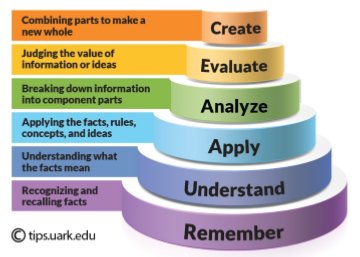

With regard to the last point, a common way of analysing teaching, learning, and assessment, is through the lens of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning (introduced in the 1950s and revised in 2001, detailed in Krathwohl (2002)). Whilst trying to avoid unnecessary levels of technicality, we do make use of Bloom in comparing some of the benefits and downsides of the various assessment approaches.

Bloom’s (revised) Taxonomy is a conceptual model which considers levels of cognition as being represented by a set of actions an individual (or student) is able to perform; depicted in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Bloom’s (Revised) Taxonomy of Learning

Source: Shabatura (2018)

Shabatura (2018) offers a clear explanation of how to use Bloom’s Taxonomy to consider the process of learning (bold in the original source), and we reproduce her explanation here:

- Before you can understand a concept, you must remember it.

- To apply a concept you must first understand it.

- In order to evaluate a process, you must have analysed it.

- To create an accurate conclusion, you must have completed a thorough evaluation.

In addition to thinking more broadly about cognition, this type of framework allows us to evaluate and reflect upon what level of learning an assessment is examining (i.e. does my assessment merely test student’s knowledge, or does it require students to demonstrate higher-order cognitive skills?).

Below, and throughout the remainder of this section, we discuss the pros and cons of various remote assessment techniques and provide some advice for their implementation under the current scenario. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide, we also describe how effectively these various approaches can be used to assess different levels of cognition.

Finally, given the level of concern amongst some sections of the academic community, we also provide a critical consideration of issues of academic malpractice – both with respect to the individual assessment types, and more generally in section 3.7.

3. Type of assessments

Here we propose six different options and some ideas on how to implement them, and the potential issues you may encounter during implementation.

One common advice in this period is: “it is not a time to innovate or be creative”. We do not completely agree with this. At a time when we face one of the major challenges to which we need to provide solutions to ensure we continue to deliver our courses and support our students; we need to be creative and sometimes adopt changes that are outside our comfort zone.

That said, we need to counterbalance assessment innovation with the disruption this may create for students. While it is a busy period for us, for students getting a degree is an important moment in their lives and assessments will affect decisions on grades, progression, degree classification and employability opportunities. Therefore, we need to set assessments that test students’ engagement with the module, but do not add technical, organisational or implementation burden that may affect their performance.

Therefore, good communication and support on any assessment decision we make must be an integral part of our strategy, even if we set an assessment that is as closed as possible to what we have planned, the circumstances through which students will be working on these assessments are not, and universities need to work on how to adapt to this.

3.1 The Nuclear Option: Cancel it

Dependent upon your institution’s regulations, the simplest approach for dealing with your assessment may be to cancel it. There are a few things you need to consider if pursuing this option:

- Have you already assessed all the learning outcomes associated with the module, such as through other assessments or coursework?

- Have students had an opportunity to demonstrate their competence such that you can infer their likely overall performance from the assessments already taken?

- Linked to the above, is the assessment you need to rearrange sufficiently low weighted that you can reasonably say that students have undertaken enough assessment to test their competencies?

If your answer is yes to two or all these questions, you may seriously consider PRESSING THE RED BUTTON! (i.e. cancelling the final assessment). This option is clearly subject to institutional regulations and/or the measures they put in place to deal with the present circumstances.

Of course, this is not challenge-free. Some students may be counting on the final assessment to improve their marks, with some putting lots of efforts into addressing feedback they received in previous assessments in which case, any extrapolation of existing marks is unlikely to reflect their actual preparation.

However, if this is a low-stake assessment, this will have little effect on their overall degree. There is an extensive literature (e.g. Barry et al., 2010; Knekta, 2017; Wise and DeMars, 2005) which looks into student effort and motivation where stakes are low; finding (amongst other insights) the idea that low stakes test exhibit much greater variability in student motivation and effort than high stakes. A non-negligible benefit of cancelling low-stake assessments is that students will have more time to focus on their remaining assessments.

3.2 Time-limited on-line exams

Time-limited on-line exams are, arguably, the closest we get to traditional exams. This consists of making the exam questions available on the university Virtual Learning Environment (VLE)[1] such as Moodle or Blackboard, and giving students a limited amount of time to complete the task (perhaps comparable to the original exam time limit).

If replacing traditional exams, many universities may be opting for this type of assessment, and there are some valid reasons for this to be the default option. First, if exams are already written, lecturers may not need to write a whole new assessment; such re-writing exams could put a further burden on (professional services and academic) staff time, who may already be very busy. Second, this type of assessment will be very similar to that which students are expecting; in the UK, students usually know the structure of the exam in advanced and past exams are available to help them prepare - so this may be an opportunity to offer some continuity in a very challenging period. There are, however, also reasons why the use of exams is less valid; the prime example of which is where exams are chosen solely because they offer a path of least resistance (probably one of the main reasons so many courses rely so heavily on exams).

Irrespective of the rationale for the employment of this approach, there are several considerations which cannot be overlooked. It is important to ensure that exam questions do not simply ask students to replicate information that it is easy to find in textbooks or other re- sources. While this will be poor practice even for in-house, invigilated exams, remote written assessments become de-facto ‘open book’, such that students have access to their notes and course texts while completing the exam. In this case, assessment is not a useful an indicator of students’ performance and engagement with the subject; possibly failing even to satisfy the lower reaches of Bloom’s Taxonomy. In this case you may wish to redesign questions such that they require students to demonstrate understanding, or apply their knowledge to a case study, rather than simply reproducing theory or content (Race, 2014).

Multiple choice can be employed in these types of exams and most virtual learning environments have inbuilt tools to allow their creation. Devising and/or preparing online multiple choice tests will clearly impact on the time it takes you to revise your assessment and setting good multiple choice questions that assess more than simply the capacity to choose the correct definition takes some time, but pays off when marking submissions (as does any type of multiple-choice test). Online multiple-choice testing also usually permits the drawing of a set number of random questions from a larger bank; this can help reduce the risk of student communication, but obviously comes with the need to ensure that all questions are of comparable difficulty.

Time-zones represent one of the biggest challenges to these assessments. Given the level of internationalisation in the UK universities[2] students will be sitting exams at different times and it may be very difficult (almost impossible) to find a time that is not inconvenient for some students e.g. in the middle of the night.[3]

One way to overcome this may be using dynamic timing: Students have a time window in which the test is available to view or download, but once begun students have a strictly limited amount of time to complete the work. In this case, the initial windows needs to be broad enough to allow all time-zones to access the exam at a convenient time (e.g. any time between 9am and 2pm UK-time should work for 3-hour examinations) and complete the exam. Some VLEs such as Moodle may allow to set these exams, but otherwise you need to check with the university IT services on the technical feasibility of this option. Another alternative would be having two similar scripts, one to be released in the morning and one in the afternoon, so students will have the option to choose the one is more convenient for their time zone. Of course, you need to write two different scripts and guarantee that these are of similar difficulty.

We cannot forget that some students need special arrangements when sitting exams. If these are dealt with by offering extra-time, this may not be a big challenge, but if they require other type of arrangements (e.g. special IT equipment), these may more difficult to set up under the current scenario, and will add unnecessary stress and anxiety to these students.

You may also encounter issues with resources. If you rely on one or few textbooks that have no e-book versions, it is important that students have access to these for their preparation, and during the exam. Many students still rely on library copies for revision, and given that libraries are closing, some students may struggle during revision period. This will be bad for almost every assessment but will be particularly intensified in open-book time-limited exams, when having the book is a clear advantage.

Similarly, access to internet may be restricted in some countries. If this is the case you may need to check that resources available on your module’s VLE (Moodle, Blackboard, etc.) page are not restricted or under commonly restricted websites (e.g. YouTube).

Another challenge with time-limited online exams is how to deal with late submissions (in the case that the submission is not automatic). In an exam hall, we simply collect the exam at the end of the established time, but this becomes more complicated for online submissions. Rather than refusing to accept late submissions, you may want to apply late penalties.

Finally, during exams, every single minute is important for students, so they will work until the end. Therefore, there are going to potentially be many students submitting at the same time and universities need to ensure the systems can cope with this since, with short time frames, potential system failures may have large effects. For many universities, it will be the first time experiencing this type of scenario, so if the system fails you need to be prepared for how you will deal with such a situation.

3.3 Take-home assessments with more conventional time windows

Assuming your module does not feature “students will be able to reproduce course knowledge in a time-pressured environment” amongst its learning outcomes, another option may be to simply set a conventional take-home assignment. Discussion- or essay-based exams would lend themselves well to become take-home assignments where students have, potentially, several weeks to complete the task. How long students are given may be related to the overall length of the exam, but you might adopt a rule of thumb, e.g. one week for each hour the exam was scheduled to last.

This type of assessment may present fewer technical and organisational barriers than other types of alternative assessments making it very appealing. There are no problems with time zones, and there should not be technical issues (not more than in ‘normal’ times), but this is not the only reason to choose this type of assessment.

As with regular, well-designed, essay-type coursework In order to work on this assessment, students will rely less on one single source (e.g. textbook) for which an electronic copy may not be available. This will address the issue of not physical having library access in this period but remind students on how to access online resources using their library credentials, for example by providing a link to the library resources.

Written assessment with longer time for completion (essays being the typical example) may be associated, variously, with the opportunity to integrate and apply relatively complex ideas (Cook and Watson, 2013); as such they present an appealing alternative to the potentially superficial responses associated with unseen exams.

Should you choose to set a take-home assessment with longer time for submission, there are also many options available beyond simple essays, including reviews and annotated biographies which require students to engage with literature (Race, 2014), or broader problem-based approaches (outlined extensively in Bean (2011)) such as research projects, responding to to positional statements,[4] blog entries, etc.

Whilst we have this amazing and exciting range of alternative take-home assignments that we might consider in lieu of an exam, it is important to make some considerations. While they may encourage a deeper level of analysis, individual one-off assignments placed in lieu of an exam can result in uneven assessment of the course topic: always consider coverage when setting an alternative take-home assignment – does it assess all the points of the course that would have been assessed by the exam. Given previous assignments on the module, does it need to?

Another potential disadvantage of this type of assessment may be the marking work-load. Because well-designed essays encourage students to think at a deeper level, they are often more challenging to mark. So, if you have a large cohort, this may not be the best option, even with support of extra markers; a marking team needs to be coordinated, and some good moderation involved in order to guarantee consistency across the different markers.

Finally, if moving beyond a conventional essay, it is important to ensure that students are sufficiently prepared for the requirements of the task; all assignments are themselves tests of students’ ability to understand the task. Confronting students with a task for which they are unprepared is likely to result in under-performance and student dissatisfaction.

Last but not least, given the high stake that final assessments usually carry, you may be worried about students colluding, plagiarising their answers, or even buying their work. While these practices DO exist, appropriate assessment design can help to mitigate against misconduct. Good assessments which require students to engage in creative and original thinking, or require students to produce original ideas and solve problems, make it far harder for students to draw their ideas directly from other students or sources. Examples include requiring students to make an informed judgement about something, e.g. recent political events or an economic policy decision. There is not a single right answer for these assessments, so you will be marking students’ reasoning, interpretation of the problem, and how they use theories and concepts in the decision-making and problem-solving process.

Even in the best designed take-home assessments, students may communicate with each other in order to exchange ideas on the assessment, but this is no guarantee that they will reach (or even agree on) the same conclusion; such communication and negotiation of knowledge and understanding can even be beneficial to students. Moreover, should you still need convincing, remember that online submissions and the use of plagiarism software (e.g. Turnitin) can deter students from collusion and plagiarism, especially if the assessment has a high weight in the final mark (but be sure to remind students that you use these methods). To deal with students buying essays from essay mills may require a slightly different approach and we discuss this further in Section 3.7 (see Burnett, 2020).

3.4 24h/48h Assessments

Even where the exam itself does not naturally lend itself to a longer take-home window (as you might expect with more technical or mathematical exams), you may not want to rule out the possibility of setting a different take-home assignment in lieu of the exam. Instead of a long deadline assessment, you can opt for a shorter time window to complete it, such as 24 or 48 hours.

This assessment has a series of organisational advantages, none less that students may be familiar with them, as they are usually used as formative[5] (or low-stakes summative[6]) assessments. They also help to deal with time-zones issues as all students have 24-hours from the release of the homework to complete the task, so there is less pressure on working at inconvenient hours. To this regard, 48-hours assessments might work even better. We need to keep in mind that there are going to be few assessments happening at the same time and, if students have other examinations in a similar time-frame, 48h may help to reduce time-pressures and allow better organisation (and some sleeping time!).

There are also educational advantages. Compared to assessments with extended sub- mission times, students will be less prone to focus on what they believe is relevant for the assessment, and engage with the syllabus more broadly, as they will prepare in advanced. There is also less time to engage in academic malpractices (e.g. buying essay answers). Compared to online exams with shorter-time limits, 24h assessments offer the advantage that students can reflect and improve the quality of their answers, but we need to set questions that promote this reflection.

Again, as with the previous types of assessment, 24-hour window exams have their own specific challenges:

You need to give particular thought to the design of the assessment. Questions should be set in a way that require students to go well beyond recalling information/ concepts/theories that can be easily retrieved (and hopefully this is the case for all assessments). Similar to assessments with long-submission times, questions should require students to engage in original thinking and critical assessment, but in this case, they have a much shorter time-frame.

When designing the questions, keeping in mind the time-frame available is important. Some may be tempted to set up questions that require very long-answers: after all, students have 24 (or 48) hours to write an answer. However, we should not be designing assessments, such that students must spend 24 hours writing. In fact, for each question we should set a (realistic) word-limit so students are not tempted to just add all the information available, but need to be concise and selective in their expression (i.e. need to judge the value of information/ideas to demonstrate the higher order skills of Bloom’s taxonomy; outlined in Section 2.3). Word-limits will also facilitate the marking process, as you limit what you have to read and mark.

24-hour assessments can be also used for mathematical/statistical questions, that may require some interpretation of the problem or data provided. However, there is the risk that students do collude and, if the answers only require the computational results, it will be very difficult to detect collusion. Requiring students to interpret the results, and given a greater weight to this interpretation should (at least) partially address this issue.

You can also use 24/48h assessments in more interesting/engaging ways. For instance, you can require students to write policy briefs or short-videos of determined topics of the syllabus (remember to add a word-limit). Those students who are familiar with the syllabus material, will spend more time in using this information to write the brief (or make the video), but those who have done little preparation will spend more time in reading the course material and their briefs may not provide enough in-depth consideration of the issue.

As with any other reorganisations of assessment, it is important that students know the structure and understand what is expected from them before the questions are released. This will help them to organise the material and be ready to focus on the assessment.

3.5 Online Vivas (oral examinations)

In oral examinations (viva, viva-voce), students are interrogated about selected parts of the syllabus through various questions. This is the typical examination method for PhD candidates, but it is less common for undergraduate or taught postgraduate modules in the UK. Under the current scenario, this could be one examination option.

By now most of us have had at least one online meeting by Zoom, Skype, Microsoft Teams, etc. Not sure how you feel about these, but some may be wondering ‘why we don’t do this more often?’, especially in those occasions when we are technically free at at specific time, but in a different location.[7] We can use this technology to carry out viva examinations.

On the organisational side, one advantage is that we can set up times that suit all time zones, so students do not have to be examined at inconvenient hours.[8] It is also quite easy to set as we have all technology available: Skype, Zoom, which allow to even record the Viva exam for future moderation. On the educational side, there is very little risk for students to engage with academic malpractice (i.e. cheating), which may be the main worry with remote assessments.

Race (2014) explains advantages and disadvantages of vivas. They offer the opportunity to develop practical skills such as practice for employment interviews, and help to evaluate verbal communication skills. However, some students may feel less comfortable with this type of assessment which may lead them to under-perform. Additionally, a second marker may be needed during the interview, so that both markers can discuss on the final mark immediately after this takes place.

3.6 Assessing more than one subject

Most of the decisions on assessments are based on a modular basis i.e. there is one assessment per each module/subject but, given the circumstances, why not set assessments that assess more than one subject?

Taking as example Economics graduates, they will rarely be tackling an issue only from a macroeconomic perspective rather than from an industrial economics angle, and more likely employment tasks will require them to provide a discussion/solution/interpretation of a problem, and they will need to use their knowledge background to do this.

In order to assess more than one subject, you can be quite creative with the structure of assessment. While it may not make much sense to set time-limited online assessments to assess more than one subject, almost all the other assessments here described can be used. An assessment with long-submission time or 24/48 hours assessments that requires students to use ideas/theories/models from more than one module, may require higher- order thinking skills as, depending on the question(s), students need to combine concepts learnt in different modules, in order to provide a good answer.

An assessment for Economics students based on writing a policy briefing or research report on “The effects of a pandemic on the UK labour market” can easily be used to test Macroeconomics, as students need to make macroeconomic considerations (e.g. budget constraints, redistribution policies), Labour Economics, as this will affect the labour market, and even more statistical modules such as Statistics or Econometrics, if we add a data analysis component.

An important aspect for the success of these assessment is to design and set clear marking criteria and to communicate this to students. You need to consider how the mark will be distributed across all subjects e.g. would all subjects get the same mark, or different sections of the problem set will be marked differently according to which subject they relate?

In addition, students’ ability of merging and using knowledge from different subjects need to be credited, and you need to decide how this extra-credit will be distributed across the different subjects. This requires collaboration with colleagues teaching other subjects, and coordination on the assessment methods.

Of course, another challenge is that students do not all do the same modules, as many of them will have the opportunity to choose subjects from a list of options, and even from other disciplines. So perhaps these assessments may work better for ‘core modules’ (i.e. those modules that are compulsory for a degree course) or a combination of one core and one optional module, which requires more coordination among different parties.

Despite the challenges, this assessment can be a very enriching experience for all. Academic staff would be able to set up meaningful teaching-collaborations beyond co-teaching a module, that unlike research-collaborations may not happen that often. For students, being able to use their knowledge from various subjects in one assessment may offer the opportunity to develop important employability skills.

Being able to apply subject specific course knowledge to ‘real world problems’ is highly appreciated skill by employers, but students may not have the opportunity to develop enough during their careers (see e.g. Jenkins and Lane (2019)).

3.7 An additional note on “cheating”

We understand cheating is one of the most common concerns regarding any sort of take-home assessment. In fact, the main reason why in-presentia, time-limited exams are the preferred assessment method is that we consider they minimise students’ likelihood of ‘cheating’ or other disallowed behaviour. However, evidence suggests that we underestimate the probability and incidence of exam room misconduct, while simultaneously overestimating the dangers of misconduct associated with take-home assessment (Bretag et al., 2019a).

It is important, first, to understand that cheating does take place in exams, perhaps more than we expect. Bengtsson (2019), Bretag et al. (2019a), and Burnett (2020) all suggest that cheating in exams is a relatively common practice. Specifically, Bretag et al. (2019a) find exam-based cheating to be more prevalent than any other type of misconduct, while Burnett (2020) finds that self-declared exam-based cheating amongst UK students is nearly three times more common than commissioning of written work. Furthermore, although the physical presence of academic staff in exam rooms might give the illusion of control and effective surveillance, academic staff are frequently not trained or prepared for the task of identifying malpractice in this environment.

Take-home assessments differ in the way that detection takes place, being carried out after the work has been submitted, rather than trying to detect while work is taking place. In most cases monitoring also features the delegation of detection to plagiarism software (such as Turnitin). This makes detection of plagiarism and collusion much more reliable and far less reliant on human vigilance (as in the case of examinations).

We understand that the use of conventional plagiarism software still leaves the spectre of commissioning of written work by students. while the full extent to which students actually buy work is unknown (estimates vary wildly), there is a growing consensus that assessment design can significantly mitigate against the risk of commissioning. To this end, it is important to understand that some assignments/questions are easier to contract out than others; essay titles which simply require students to demonstrate their knowledge of, or describe a theory can be very easily completed by any individual with a basic knowledge of a subject and a willingness to open a textbook. On the other hand, assessments which promote higher order learning, and which draw on specific aspects of your course are much more difficult to ‘farm out’ (Bretag et al., 2019b; Rafalin, nd). Good examples might include asking students to personally reflect on specific examples you provided in class, or to work with theories/concepts unique to your course; these types of reflective task make it much easier to identify where content has been produced by an external individual.

A final point regarding malpractice is to bear in mind that this is a behavioural issue. Punitive policies, enhanced detection, and exam-room surveillance are all technical solutions to the issue, but none seek to directly change the underlying behavioural aspects; all exhibit elements of ramping up measures to treat symptoms without addressing the root cause.

Survey evidence in Burnett (2020) suggests that, for almost all types of misconduct, students believe the primary motive for engaging in malpractice is a lack of motivation (or ‘laziness’), generally followed by a lack of engagement with the course. Crucially, the only category of misconduct where students believe the primary motive is a desire to cheat or gain an advantage, is exam-based malpractice. The implication of these results is two-fold:

- Academic malpractice in take-home assignments may be the product of disengaged and/or disinterested students and, thus, can be reduced through

- Owing to the different motives involved, similar measures are unlikely to be effective in addressing in-exam cheating.

In short, in terms of the academic integrity, we may be promoting the idea that exams are more ‘secure’ than the evidence suggests, while overly concerning ourselves about mal- practice in written assignments, where we have the tools to deal with it.

4. Some final thoughts on assessment

Under the current scenario, universities and staff will face a number of challenges and changes, including how to set final assessments for students. While all this will inevitable create some extra-work, we really hope this guide helps to think about how to set these alternative assessments, but also that we can take some of this learning and apply it in the future design of our modules.

Assessment for lecturers can be an after-thought: something you work on once you have finished the lectures. Even dedicated colleagues, who put lots of thoughts and efforts in organising lectures and teaching material, might give less consideration to the assessments. Thinking of what are we assessing, and why are we assessing while designing our modules, has the potential to engage students with the subject and even improve our design of more effective teaching material in the future.

While we do understand the need to make fast decisions as these need to be communicated to students, we hope these are made taking into account not just practicalities at institutional level, but considering what is best for the students and the subject-level specificities. Lack of careful planning and defaulting in the obvious options may save sometime now, but has the potential to create more work later.

Also, when considering the shift from an in-presentia, time-limited, unseen exam towards a remote assessment, one must consider carefully the learning objectives associated with the module. The assignment need not replicate perfectly the assessment of the same learning outcomes as the exam it will replace, however as a module convenor, it is important to ensure that all outcomes have been assessed at conclusion of the module.

We also hope that we convey the message that there are numerous positive aspects and advantages to take-home assessments, not least the promotion of higher-order thinking skills and that good assessment design will help to at least reduce potential academic malpractice behaviour from students, and these aspects may outweigh the potential negatives.

One extra point in favour of take-home assessments: research shows they tend to reduce student’s anxiety, which are usually high around exam period (Bengtsson, 2019). However we need to keep in mind that these are not normal times, and that students are likely to be exceptionally worried about their assessments, so independently on the option we adopt, we need to offer adequate support.

Good communication and managing students’ expectations are very important under the current scenario. Even if we set an assessment that is very similar to the original planned, the conditions under which students will take these assessments are not the same, and therefore we cannot assume students’ performance will not be impacted. For instance, access to resources is key for students’ preparation, and students may not have the same access to resources at home: they may not have the textbook, or even when available online, material may not be accessible to students in countries with restrictive firewalls.[9]

Despite all our efforts, some students may simply not be able to engage with assessments during the exam period. We need to build this in the current plans, and think of what additional support is required. This may mean allowing these students to return later this year or in the next academic year to continue/finish their degree. Finally, remember to create a plan to keep yourself safe and supported, as these are hard times for everybody, including ourselves.

Footnotes

[1] A Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) is the platform in which we upload teaching resources and other types of communication to students. Moodle and Blackboard are quite popular in the UK.

[2] There were 485,645 international students enrolled in UK universities in the academic year 2018/19. This represents 20% of the HE student enrolment for that academic year (HESA, 2019).

[3] e.g. if the exam starts at 9am this means a very early start (or a late night) for those based in Mexico City (3am) and in the US (ranges from 2am to 4am).

[4] A positional statement is one that asserts a particular position and provides students the opportunity to provide an evidenced and reasoned response; an example of this might be "Monetary policy as an economic tool is/is not sufficient to deal with the challenges of the Corona virus."

[5] Those assessments set to monitor student learning and provide ongoing feedback. These usually do not carry any weight in the final mark.

[6] These are used to evaluate students’ learning and do count towards the final mark.

[7] Whether you feel like this is almost certainly related to how your Skype/Zoom/hangouts meeting(s) have gone. If it was dreadful, we understand that you may have no enthusiasm and simply ask you to trust us that it is possible to have good meetings.

[8] Though the opposite may be true in that you need to coordinate meeting times across time zones.

[9] Internet restrictions are not just in place in China, but also in Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Vietnam, amongst others.

References

Barry, C. L., Horst, S. J., Finney, S. J., Brown, A. R., and Kopp, J. P. (2010). Do examinees have similar test-taking effort? a high-stakes question for low-stakes testing. International Journal of Testing, 10(4):342–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/15305058.2010.508569

Bean, J. C. (2011). Bean-Writing-Assignments. In The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom, chapter 6, pages 89–119. Jossey-Bass, 2 edition.

Bengtsson, L. (2019). Take-home exams in higher education: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040267

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenberg, P., Saddiqui, S., and van Haeringen, K. (2019a). Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university students. Studies in Higher Education, 44(11):1837–1856. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., van Haeringen, K., Saddiqui, S., and Rozenberg, P. (2019b). Contract cheating and assessment design: exploring the relationship. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5):676–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1527892

Burnett, T. (2020). Understanding and developing implementable best practice in the design of academic integrity policies for international students studying in the UK. Technical report, UK Council for International Student Affairs.

Cook, S. and Watson, D. (2013). Assessment Design and Methods. The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n2358a

Jenkins, C. and Lane, S. (2019). "Employability Skills in UK Economics Degrees." Research report, The Economics Network. https://doi.org/10.53593/n3245a

Knekta, E. (2017). Are all Pupils Equally Motivated to do Their Best on all Tests? Differences in Reported Test-Taking Motivation within and between Tests with Different Stakes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(1):95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1119723

Knight, P. T. (2002). Summative Assessment in Higher Education: practices in disarray. Studies in Higher Education, 27(3):275–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070220000662

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4):212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Race, P. (2014). Designing assessment and feedback to enhance learning. In The Lecturer’s Toolkit : A Practical Guide to Assessment, chapter 2, pages 29–131. Routledge, London, 3rd edition.

Rafalin, D. (n.d.). Designing assessment to minimise the possibility of contract cheating. City University, London.

Shabatura, J. (2018). Using Bloom’s Taxonomy to Write Effective Learning Objectives. University of Arkansas

Wise, S. L. and DeMars, C. E. (2005). Low examinee effort in low-stakes assessment: Problems and potential solutions. Educational Assessment, 10(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326977ea1001_1

↑ Top