Alvin Birdi and Ashley Lait

Economics Network/ University of Bristol

Published December 2014

In his well-known 1971 work, ‘What’s the use of lectures?’, Donald Bligh provides a sympathetic critique of the predominant method of teaching in higher education. He interrogates the value of relaying information to students in a large lecture theatre, a process that may neither promote deep learning nor inspire great interest in the subject.

Yet four decades on, the lecture continues to be the mainstay of teaching provision in most higher education institutions, and with increasing student numbers and pressure to ‘up’ the quantity of contact hours, it seems unlikely that they will disappear from timetables any time soon. Nevertheless, the calls to scrap lectures all together remain, with arguments such as ‘why retain the face-to-face lecture when its value as a pedagogical tool is so limited? There seems to be no other reason that the old justification: “we’ve always done it this way”’ (Clark, 2014).

While it is certainly true that many lecturers still deliver their classes in the traditional ‘lecturing’ style of reading notes or going through PowerPoint slides, there have been various innovations that are recasting the lecture. These teaching tools may be slowly reinventing this staple of university life. In what follows we highlight three of these innovations.

While it is certainly true that many lecturers still deliver their classes in the traditional ‘lecturing’ style of reading notes or going through PowerPoint slides, there have been various innovations that are recasting the lecture. These teaching tools may be slowly reinventing this staple of university life. In what follows we highlight three of these innovations.

Clickers or polling technology

The use of clickers or other classroom response systems (including polling software or apps on personal devices), which allow students to individually and/or anonymously respond to questions, brings an interactive element to lectures that teachers have struggled to achieve in large class settings since the widespread use of pre-prepared Powerpoint slides. Victor Edmonds of the University of California at Berkeley points out that: ‘Putting up your hand in class is a pretty complex thing, kind of dangerous, socially and academically. But everyone is willing to give anonymous answers’. The value of clickers in increasing interactivity has been attested to in a number of studies (Stowell & Nelson, 2007; Freeman et al., 2006).

The use of clickers or other classroom response systems (including polling software or apps on personal devices), which allow students to individually and/or anonymously respond to questions, brings an interactive element to lectures that teachers have struggled to achieve in large class settings since the widespread use of pre-prepared Powerpoint slides. Victor Edmonds of the University of California at Berkeley points out that: ‘Putting up your hand in class is a pretty complex thing, kind of dangerous, socially and academically. But everyone is willing to give anonymous answers’. The value of clickers in increasing interactivity has been attested to in a number of studies (Stowell & Nelson, 2007; Freeman et al., 2006).

“Perhaps less evident is the role polling technology can play in facilitating peer learning”

However, despite the fact that students have reported that they find clickers useful (74% of students in Wit’s 2003 study thought the handsets were useful to very useful in aiding their understanding) and many lecturers accept the value of clickers to break up lectures and promote engagement, questions remain about the pedagogical worth of this technology. So, are they just a gimmick or are there more benefits to integrating clickers into large group classes?

Classroom response systems stream students’ responses live to the lecturer’s computer and they can then be displayed in graphic format on a projector screen. The lecturer is able to see whether students have understood the material, identify any areas of difficulty and provide relevant and timely feedback; which in the past has only really been possible in smaller group teaching environments. Jon Guest at Coventry University has found that ‘with a traditional way of monitoring whether learning is taking place, the same students always answer the questions and there is no way of knowing if they were representative of the group as a whole. Clickers are able to overcome this problem. By periodically setting questions embedded into a PowerPoint presentation, it is possible to obtain more reliable and representative feedback on the extent to which the material is being understood’. This also enables lecturers to tailor seminars more closely to the group’s needs.

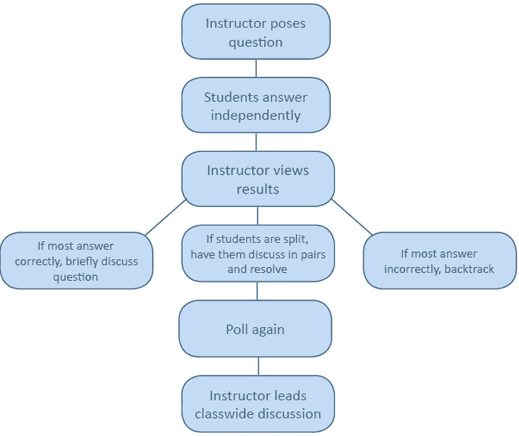

Perhaps less evident is the role recent polling technology can play in facilitating group work and “peer learning”. Mathematician Derek Bruff of Agile Learning and physicist Eric Mazur from Harvard University have been using the “Learning Catalytics” technology to encourage students to learn from each other. Unlike some other polling technologies, this one allows graphical and free-form input which may be of particular use to technical subjects such as economics. It also allows the instructor to see in real time the understanding shown by every individual in the lecture. Mazur uses these individual responses to create pairs of students who have different (perhaps opposing) answers to a question so that they can try to convince each other at an individual level during the lecture. Only after this peer learning takes place does he reveal the correct answer to the problem.

Adapted from D. Bruff (2011), "Teaching with clickers for deep learning". See the video demonstration of Eric Mazur using this method.

Polling technology used in this way is not merely engaging the students in an interactive way, but it is inviting them to justify, reason and communicate their answers with peers, developing some of the vital skills that we look for in our learning outcomes and which are valued highly by employers.

Finally, clickers may have an additional use for economists: lecturers are able to save the raw data they collect through polling their students, providing valuable data that might be analysed to better understand and reflect on their courses.

There are increasing numbers of providers of this hardware and/or software including:

- Turning Technologies

- Konnect

- Learning Catalytics

- Poll Everywhere

- Socrative

Lecture capture

This technology, now widely available in UK universities, enables teaching staff to record their lectures and make them available to students online, usually via a virtual learning environment. One of the clear benefits of lecture capture is also touted as its main downfall: students can catch up on classes they miss. While it is therefore a useful tool for legitimate absences, this raises significant concerns about videoed lectures replacing the ‘real deal’, resulting in a drop in attendance. However, as Caroline Elliott has found: ‘lecture recordings appear to be used to supplement rather than replace lecture attendance’ as there was no obvious fall in student numbers in classes. This is supported by a number of other studies, including those by Bongey et al. (2006), Toppin (2011) and Copley (2007), which found that only a small number of students would be tempted to miss a lecture because they see the recording as a substitute.

The idea of recorded lectures as a ‘supplement’ is certainly the intended use of this technology. Being able to watch a lecture several times or even in sections makes this a useful tool for revision prior to an assessment or to clarify parts of the lecture that students may have found challenging when first introduced, which is ‘of particular value for international students and students with special learning needs’ (C. Elliott, 2014).

The idea of recorded lectures as a ‘supplement’ is certainly the intended use of this technology. Being able to watch a lecture several times or even in sections makes this a useful tool for revision prior to an assessment or to clarify parts of the lecture that students may have found challenging when first introduced, which is ‘of particular value for international students and students with special learning needs’ (C. Elliott, 2014).

“67.7% of students affirmed that using recorded lectures was very beneficial to their learning”

Less immediately obvious are the advantages of lecture capture that can be felt by teaching staff, for example: without the pressure of needing to complete a full set of lecture notes before the end of the hour, students are able to listen and engage more in the class knowing the material will be available online later. Or that demands on lecturers’ time in the form of repeated questions about the same problematic issue may be reduced because difficult concepts are clarified by watching the videos.

In addition to concerns about attendance, the introduction of lecture capture led to doubts about how much it would be used, especially when significant university funds and time were going to be spent. However, it has turned out to be very popular with students: Elliott’s study found that at least 84% and 95% of students accessed videos in the two years of the study, while Toppin reported that 67.7% of students affirmed that using recorded lectures was very beneficial to their learning.

There are a range of lecture capture software available including:

- Collaaj

- Panopto

- Echo360

- Mediasite

- Kaltura

- Tegrity

- Prezi

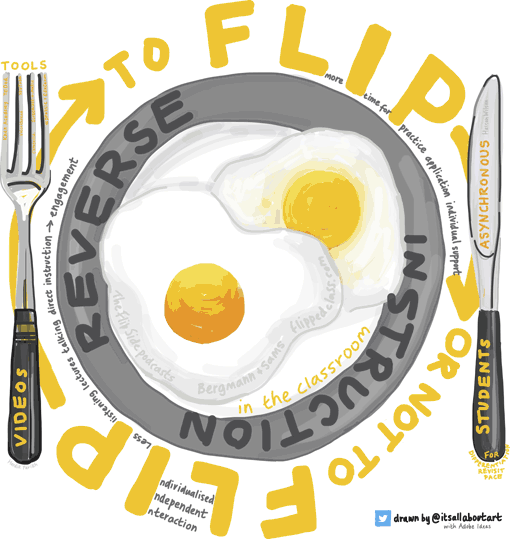

Flipping the classroom

In ‘flipped’ classrooms, students are first exposed to subject material before the lecture (often through short videos and readings) so that class time can be used more effectively for student learning. The idea is that students cannot sit passively in the class, but instead must use this time to engage in activities that are often considered part of their independent study or homework, such as problem solving, applying what they’ve learnt and working with peers (Berrett, 2012).

Above all, the flipped approach is student-led. By using videos, students can tackle the material at their own pace and repeat sections if required, something that has never been possible in a traditional lecture. The time in class can then be used to focus on topics and concepts students found difficult when first introduced to the material (Brunsell, 2011). Jon Guest, for example, asks his students to watch short videos before the lecture and then uses clickers in the lecture to assess their understanding of that material.

Some teaching staff are concerned about the time required to create videos, podcasts and reading lists necessary to adopt a flipped approach. These are certainly legitimate concerns but there are resources available online to aid the process of production and videos, once created, can be used repeatedly.

“I got overwhelmingly great evidence on the provision of these clips”

For example, Ralf Becker at the University of Manchester uses a flipped approach to his econometrics lectures:

“One example where I used a flipped approach is when I ask students to watch an online lecture on Proxy Variables and Instrumental Variables Estimation before a lecture. Then I use a one hour lecture to slowly work through one applied problem: how to evaluate whether students’ attendance in peer assisted study sessions improves the grades in that course. It turns out that I can use Semester 1 data for the very students sitting in class.

I start from that research question and ask students how they would evaluate this. They quickly identify that there is a self-selection problem (i.e. good students choose to attend these sessions) such that measures of attendance in these sessions are endogenous to the problem. I have the statistical software at hand in the classroom, such that I can quickly implement student suggestions and discuss these (lectures are recorded such that students will have the chance to replicate the work afterwards). At a fairly slow pace we discuss potential avenues to tackle this problem, concluding the lecture with an attempt to solve the endogeneity problem by using an instrument. As the instrument turns out to be very weak, this attempt ultimately fails, but I don’t mind as this is a good lesson anyway.

What I do use a lot is online clips to supplement the material delivered in lectures. You could call the lectures quite traditional style lectures, but I do use clips to cover boring or technical but vital (and exam relevant) material such that I can then use the lectures to present material that deepens understanding. I got overwhelmingly great evidence on the provision of these clips”.

So what is the use of lectures?

From the outside looking into university classrooms, one would still see lecture theatres packed with hundreds of students and one lecturer stood at the front talking and pointing. So on the surface Bligh’s critique of university teaching provision seems relevant in 2014. However, from inside the auditorium, there might be something altogether different taking place. Lectures might yet have a future. As Christopher Bigsby has written:

‘Lectures have their value… The best are not those that attempt to pour information into your ear, the approach unaccountably adopted by Hamlet’s uncle when administering poison, but those that send you spinning off into your own mind. Outside the lecture theatre your real enquiry begins’.

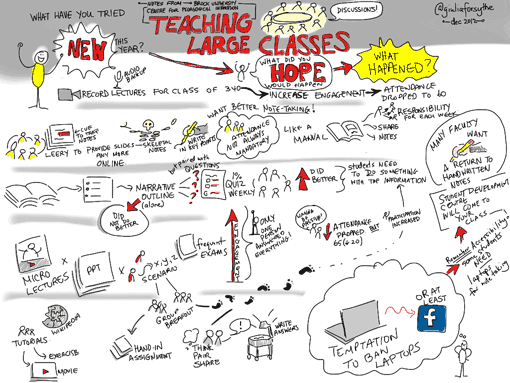

Image by Giulia Forsythe, CC Attribution-Noncommerical-ShareAlike. Click the preview to see the full-size image.

References and further reading

D. Berrett, 2012, ‘How “flipping” the classroom can improve the traditional lecture’, The Chronicle of Higher Education

S. Bongey, G. Cizadlo & L. Kalnbach, 2006, ‘Explorations in course-casting: podcasts in higher education’, Campus-Wide Information Systems, Vol. 23, Issue 5, pp. 350-367 DOI: 10.1108/10650740610714107

E. Brunsell & M. Horejsi, 2011, ‘Flipping your classroom’, The Science Teacher, Vol. 78, No. 2

D. Clark, ‘Ten reasons we should ditch university lectures’, The Guardian, 15 May 2014

J. Copley, 2007, ‘Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus-based students: production and evaluation of student use’, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 387-399 DOI: 10.1080/14703290701602805

V. Edmonds (Educational Technology Services, University of California at Berkeley) in D. Bruff, ‘Classroom response systems (“Clickers”)', Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University

C. Elliott, 2003, ‘Using a personal response system in economics teaching’, International Review of Economics Education, Vol. 1, Issue 1, pp. 80-86

J. Stowell & J. Nelson, 2007, ‘Benefits of electronic audience response systems on student participation, learning and emotion’, Teaching of Pyschology, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 253-258 DOI: 10.1080/00986280701700391

M. Freeman, P. Blayney & P. Glinns, 2006, ‘Anonymity and in class learning: the case for electronic response systems’, Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 22, pp. 568-580

I. Toppin, 2011, ‘Video lecture capture (VLC) system: A comparison of student versus faculty perceptions’, Education and Information Technologies, Vol. 16, Issue 4, pp. 383-393 DOI: 10.1007/s10639-010-9140-x

E. Wit, 2003, ‘Who wants to be… the use of personal response systems in statistic teaching’, MSOR Connections, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 14-20 DOI: 10.11120/msor.2003.03020014

↑ Top