Michael McCann

Nottingham Trent University

michael.mccann at ntu.ac.uk

Published November 2019

Introduction

This case study is concerned with the use of active assessment to address the extent of student engagement and learning. Problems with engagement and learning have provoked much discussion in economics education. Several innovations have been suggested to address the issue including problem-based learning (so that students can link economic theory and real-world phenomena) and flipped learning to free classroom time for interactions which stimulate deeper discussions (Roach, 2014; Chulkov and Nizovtsev, 2015). However, the approaches emphasise teaching and learning with little discussion of assessment in enhancing engagement and learning.

As Brown, Bull and Pendlebury (1997: 7) suggest; “if you want to change student learning then change the methods of assessment”. In most cases active learning is aligned with passive assessment activities which produce little incentive for deeper learning – closed book examination which encourage memorising and rote learning (Gibbs and Simpson, 2004). In such circumstances most students will only put in sufficient effort to complete the assessment successfully when what we really want is greater effort and deeper learning.

Our innovation presented here is consistent with the principles of constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996). We developed an active assessment design, which when linked to teaching and learning activities enhances engagement and promotes deeper learning. In doing so, the assessment enables students to apply economic concepts to real-world data and practice valuable employment skills in sourcing, interpreting and presenting data.

Context

The assessment innovation was introduced to a compulsory module in the first year covering introductory finance for economists. The module was conceived in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007-08 to address concerns about financial literacy in economics education (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014). It introduces students to financial institutions, markets and instruments, and applies economic concepts to lending and borrowing decisions. In 2014, following issues of poor engagement and weak attainment over several years, it was decided to make changes to the course.

Assessment Innovation

Our innovation was the replacement of a closed-book examination with a data-based project as the sole summative assessment. Therefore, while the underlying content was unchanged, the nature of the assessment is intended to promote ongoing active engagement with the content and develops broader employment skills. Here is an example question on debt markets and securities from the closed-book examination used before the assessment innovation:

Table 3 below shows information on UK benchmark government bonds.

Table 3: Yields on UK Benchmark government bonds

|

Maturity |

Yield (%) |

Yield 1- week ago |

|---|---|---|

|

1 year |

0.42 |

0.43 |

|

2 years |

0.57 |

0.59 |

|

5 years |

1.36 |

1.40 |

|

10 years |

2.06 |

2.12 |

|

15 years |

2.47 |

2.54 |

|

30 years |

2.83 |

2.89 |

Adapted from FT.com – downloaded on 24/11/2014

- Explain the following characteristics of bonds:

- Maturity date

- Coupon

- Par value

- Yield

(10% of marks for each)

- The yields on all of the bonds in table 3 above have fallen in the previous week. Provide two different explanations for why this might have occurred (30% of marks).

- Using a bond valuation model, illustrate and explain the market process which produces the change in price, and hence, yield observed above (30% of marks).

And here is assessment task from the data-based project which assesses the same knowledge and understanding around sovereign debt securities:

- Choose a week in January 2018. Identify the changes in the yield of a UK government benchmark bond across the week.

- Provide two different explanations for the changes in yield which you observe.

- Using a bond valuation model, illustrate and explain the market processes which produce the change in price, and hence yield observed.

In the example examination question, the students are passive learners. They are presented with data and expected to recall and regurgitate knowledge and understanding. In the example coursework task, students are actively constructing their knowledge and understanding.

Several features of the assessment design facilitates constructivism. Firstly, students select their data for analysis within specified parameters (in the above example any week in January 2018). Secondly, they apply relevant economic theory (with guidance and feedback) in order to make sense of what they are observing. The autonomy and curiosity stimulated is intended to encourage deeper, more active engagement in learning throughout the course. Further, such assessment broadens the skills students develop by requiring them to conduct data analysis in ways which may be expected of them in future careers.

In addition to the assessment design fostering active learning by requiring students to collect their own data, a key requirement is the provision of both formal and informal feedback during the course which is timely, specific and ungraded (Cooper, 2000; Nicol and McFarlane-Dick, 2006). Data analysis is demonstrated in lectures using real-world data and subsequently, students practice the required analysis during seminars receiving informal feedback. Further we employ formal formative assessment tasks periodically throughout the course. These do not contribute to the final grade but are directly related to the completion of the assessment. Students source data they plan to use in their project, present it in a usable format (normally in a spreadsheet) and submit online through the module page on the University’s virtual learning environment (VLE). Tutors provide formative feedback about the usefulness of the data and guidance on embryonic ideas for analysis.

Seminars and formative assessments encourages ongoing engagement because the feedback received is directly helpful in completing the final assignment. This approach also helps address concerns regarding scholarship levelled at un-invigilated coursework assessments. The data students submit for the interim deadlines are required to be used for the final summative project. We advise students that if they use different data, they will be penalised. Since, academic offences like collusion tends to happen in the pressurised environment of a looming deadline, committing students to data collected many months before reduces the potential for collusion since they are less likely to copy data from one another.

Evaluation

The new active assessment design was introduced in 2015/16. We evaluate the innovation across three cohorts from that period to 2017/18 with two periods previously when the examination assessment was used (2013/14 and 2014/15). Data used to evaluate the impact of the assessment innovation regime is taken from several sources. Firstly, we used student feedback collected through anonymised surveys to gauge their perceptions of engagement (See figure 1). We triangulate this with participation rates in the voluntary formative assessments to measure revealed engagement (Figure 2). Finally, we analyse the attainment from two cohorts who experienced the examination assessment and three cohorts who experienced the active coursework project. We also analyse the performance of a subsample of the students on an advanced finance year in the year after to assess whether knowledge retention improved under the active assessment regime (see Figure 3).

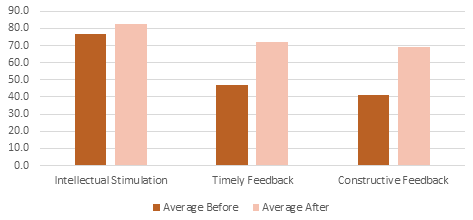

Firstly, in order to assess whether the active assessment design stimulated greater curiosity in the subject among students we asked the extent to which students found the module intellectually stimulating. There is no significant rise in the percentage of students who find the module intellectually stimulating after the introduction of the new regime. However, the impact on their perception of assessment and feedback is significant. The percentage of students reporting both timely and constructive feedback for their work is significantly higher after the assessment innovation was introduced. This indicates that students were more engaged, recognising the opportunities for regular formal and informal feedback under the new assessment regime.

Figure 1: Percentage of students who agreed with the statements

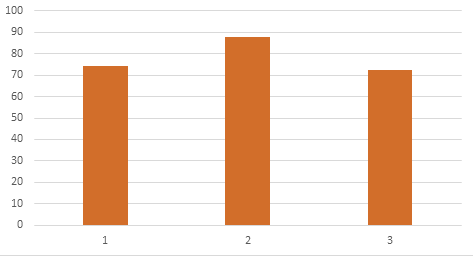

This high perception is consistent with the percentage who participated in the formal, formative assessments (See figure 2). The formative assessments do not contribute to the final grade yet the results suggest that when directly linked with the requirements of the summative assessment, engagement is high.

Figure 2: Participation rates in Formative Assessments

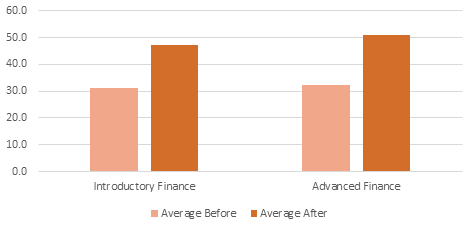

We use attainment levels to assess whether greater engagement with assessment and feedback stimulates the deeper learning which produces higher levels of attainment. We analyse the attainment levels in the introductory finance course itself and the performance of a subset of students in advanced finance modules in subsequent years to determine whether they retained more of what they learned - evidence of deeper learning. While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions because of the number of variables influencing performance, the results indicate higher attainment levels, on average, after the change in assessment regime.

Figure 3: Percentage who achieved 2.1 or above in Summative Assessment

Summary

We introduced an active assessment regime on an introductory finance module delivered to first year economists. The innovation aims to stimulate greater active engagement and deeper learning as well as develop valuable employment skills in data analysis. Evidence indicates that the need to actively source and analyse data during the module encourages students to seek and receive regular feedback. Further, a greater proportion are evidencing deeper learning through higher levels of attainment both in the introductory finance course and subsequent advanced finance courses. We believe that such active assessments are most useful in modules where students can use data to apply economic theory to real-world issues.

References

Biggs, J., 1996. Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment, Higher Education, 32: 347-364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Brown, G., Bull, J. and M. Pendlebury, 1997. Assessing Student Learning in Higher Education, London: Routledge.

Chulkov, D. and Nizovtsev, D., 2015. Problem-based learning in managerial economics with an integrated case study. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 16(1):188.

Cooper, N., 2000. Facilitating learning from formative feedback in level 3 assessment, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 25: 279-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/713611435

Gibbs, G. and C. Simpson, 2004. Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning, Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1: 3-31.

Lusardi, A. and Mitchell, O.S., 2014. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1): 5-44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.1.5

Nicol, D. and D. Macfarlane-Dick, 2006. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback, Studies in Higher Education, 31: 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Roach, T., 2014. Student perceptions towards flipped learning: new methods to increase interaction and active learning in economics, International Review of Economics Education, 17: 74-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2014.08.003

↑ Top