Prevention and Detection of Plagiarism in Higher Education: Paper Mills, Online Assessments and AI

Carlos Cortinhas and Szabolcs Deak[i]

University of Exeter

Corresponding author: c.cortinhas at exeter.ac.uk

Published November 2023

This chapter builds on (and extends) a previous version written by Jeremy B. Williams entitled Plagiarism: Deterrence, Detection and Prevention which was written for the Economics Network in 2005 and a previous version written by Carlos Cortinhas entitled Detection and Prevention of Plagiarism in Higher Education in 2017.

↑ Top1. Introduction

Charles Caleb Colton once observed that ‘imitation is the sincerest form of flattery’. Whilst this may be apt in many instances, there is a point in the intellectual space where imitation is more akin to theft. This is certainly the case in the higher education sector where, in the internet age, the increasing incidence of student plagiarism has become an ever-increasing cause of concern.

Plagiarism may be defined as the use of another person’s words and/or ideas without acknowledging that the ideas and/or words belong to someone else for someone’s own benefit. It is not a new phenomenon, but there is little doubt that it is a growing problem that lecturers and universities need to address systematically if the underlying causes, rather than the symptoms, are to be addressed.

The problem is not limited to Economics but given that Economic departments tend to have a significantly higher number of students than other degrees, above average class sizes and a significant proportion of international students, it is arguably more likely to be of especial relevance to economics academics.

At the heart of the problem is not only the increasing availability of easily accessible electronic resources, whereupon it has become so much easier for students to ‘cut and paste’ slabs of unedited text but it has become much easier to order a complete, bespoke piece of work from one of the many available online providers. This can sometimes lead to assignments being submitted that are inadequately referenced, highly unfocused or, worse still, largely or entirely someone else’s work. The recent developments in the field of generative artificial intelligence (AI) are likely to exacerbate the problem.

This chapter considers the various strategies currently being employed to stamp out plagiarism. These include the use of ‘honour codes’ that incorporate punitive systems to discredit plagiarists and the various proprietary and freeware packages available for the electronic detection of plagiarism. More importantly it discusses some practical prevention strategies that includes designing and implementing types of assessments that make plagiarism more difficult to take place.

The discussion will concentrate, first of all, on the defining characteristics of plagiarism and how it manifests itself in the current university environment. This is followed by a brief discussion on the factors deemed to be responsible for plagiarism, and the mechanisms subsequently employed by various institutions to deal with its increasing incidence. The discussion concludes by arguing for an integrated approach founded upon a commitment to assessment regimes that reward critical analysis rather than content regurgitation, something that is particularly relevant in the context of AI.

To proceed down this path, it is further argued that assessment items need to be designed in such a way as to present students with authentic learning environments: that is, settings for assessment that engage students with real and relevant tasks, with palpable and practical learning outcomes. Of all disciplines, economics is one that readily lends itself to this approach.

The main aim of the discussion is, therefore, to demonstrate that, while introducing measures to improve deterrence and detection of plagiarism is important, this is essentially a reactionary approach. It is unlikely to yield lasting benefits and might not be efficient to stamp out the most serious types of plagiarism. It is argued that the source of the problem is systemic, and that the focus needs to be on prevention of plagiarism through the use of innovative and engaging assessment. To this end, it is further posited that information and communications technologies (ICTs) can be of invaluable assistance – the very technologies that have led to the burgeoning student plagiarism problem in the first place.

↑ Top2. Plagiarism in Higher Education

‘Plagiarism’ derives from the Latin word plagiarius, meaning ‘kidnapper’ or ‘abductor’. It is the theft of someone’s creativity, ideas or language; something that strikes at the very heart of academic life. It is a form of cheating and is generally regarded as being morally and ethically unacceptable.

It should not be surprising, therefore, that plagiarism is such an emotionally charged issue and that agreeing on what plagiarism is might not always be an easy task, especially when we talk about punishing this practice. Plagiarism can be the result of sloppy referencing, honest errors, and different cultural and ethical values with respect to academic work.

Therefore, one key aspect when we deal with plagiarism must be the intent to plagiarize and the fact that intent is not always easy to prove might explain the very small number of students that are punished with expulsion from their universities (see section 2.3).

Top Tips 1

- Always ensure that you are familiar with your institution’s plagiarism policies and regulations, and be able to explain them in jargon-free terms to the students.

- Strike an appropriate balance between ‘encouragement’ of the learning process and the potentially serious consequences if plagiarism is proven.

- A worthwhile exercise is to spend some time in class (or interactively online) going through real examples of what does and does not constitute acceptable practice. A suggested method of doing this is contained in section 2.5.

2.1. The different types of plagiarism

Given the dramatic increase in its incidence, most universities around the world have made a point of including definitive statements on plagiarism in student handbooks and on university websites in the hope that no student standing accused of plagiarism can mount a defence on the grounds of their ignorance[1]. The fact remains, however, that even proceeding on the basis that all students are diligent enough to read the ‘fine print’ in university policy documents, the scope of plagiarism is such that it incorporates a range of offences not easily defined in the space of a few sentences. In short, there will be instances where the extent of plagiarism is very serious, others when it will be relatively minor, and times when it falls somewhere in between. As a consequence, a range of policy responses is required to match the gravity of the offence.

It is certainly important to send out a clear signal to the student body that plagiarism will not be tolerated, but it is also important to acknowledge the possibility of genuine cases of unintentional plagiarism, and to be wary, therefore, of over-zealous policing of plagiarism. In any case, it is essential that the institution be capable of distinguishing between intentional and unintentional plagiarism.

Without wanting to over-generalise, plagiarists may be identified as one of the following three types:

- the lazy plagiarist;

- the cunning plagiarist;

- the accidental plagiarist.

The ‘lazy’ plagiarist is generally an academically weak and otherwise under-motivated student, the type who would happily take the work of someone else in its entirety, do little more than to change the name on the paper and claim it for their own. This type of student may use the ‘cheat sites’, simply steal the work of others – maybe that belonging to a student who studied the subject in a previous year at a different institution or copy what a generative AI engine produces when replying to the assessment question. For this type of plagiarist, if a ready-made answer to a question cannot be found electronically, it simply cannot be worth having. The development of an educated opinion, a lively inquiring mind, a creative impulse: these things are not worthy of consideration. As a student’s e-mail signature once read: ‘Clay’s Conclusion: Creativity is great, but plagiarism is faster’.

For those student plagiarists who elect not to procure work from their colleagues or consume the services of the online paper mills, there is still an abundance of other point-and-click plagiarism opportunities. Plain, old-fashioned laziness is certainly a factor, but internet-inspired indolence has given rise to a more refined form of sloth. The ‘cunning’ plagiarist is more sophisticated than the lazy plagiarist and takes full advantage of these abundant opportunities: they are quite clear about what plagiarism is but works hard to avoid detection. Content is cut-and-paste from a variety of sources on the Web (and possibly from other students’ papers), with a view to manufacturing an answer. They may also attempt to cover their tracks through the provision of incomplete or inaccurate bibliographic details in their list of references, which make it more difficult to track their misdemeanours (Renard, 1999).

The most sophisticated lazy plagiarist is well versed on the existing plagiarism detection tools (see section 2.3 below) and knows how to avoid detection by, for example, changing every 7th word of the original text so that the automated plagiarism detection software does not pick up the offense.[2] When using generative AI, the lazy plagiarist might make some minor changes to the text, including the removal of fake references (see section 4).

The ‘accidental’ plagiarist, by contrast, is not in the least bit devious. Their transgressions arise typically because of inexperience, poor study skills, local academic norms or some combination thereof. Such students typically insert slabs of unattributed text in their essays and, when challenged, will be either embarrassed by their sloppy referencing or genuinely surprised that they have been challenged at all, claiming ignorance of the system.

In many instances, it is international students who fall into this latter category, particularly those from East Asian countries. Apart from a lack of exposure to western academic norms when it comes to academic work, these students can sometimes experience difficulty in constructing a critically analytical essay out of cultural respect for those in authority. This is sometimes mistaken for poor writing ability and/or a lack of ethics when the reality might be somewhat different. In Confucian cultures, for example, conventional wisdom is that the best ideas are those of the ancients, and their philosophy and insights are so wide-ranging that to challenge those ideas would be interpreted as quite an audacious act. Instead, memorisation and recitation are valued. It follows that to challenge ‘the truths’ handed down by ‘the sages’ who author textbooks and write lecture notes would be counter-cultural for students of this tradition (Smith, 1999).

Not everyone accepts this view, of course, and a standard response is that it should be a case of ‘when in Rome do as the Romans do’, with students observing the cultural norms of the country in which they are studying rather than those of their home country. Without going into an in-depth discussion of the validity of this argument, it is probably fair to say that first-year students, in particular, might be extended some latitude, at least until they have had an opportunity to commence with the cultural transition and adjust to the different cultural norms.

The emergence of freely available, sophisticated, AI powered language models increased the likelihood that students, even those with no intention to plagiarise, can become plagiarists. These platforms do not follow academic norms (like referencing) when generating their output and do not generally reveal the source they used, not even when they are asked about it specifically. When the AI is prompted to generate references, it “simply makes them up” (Shearing and McCallum, 2023). Therefore, they may turn any student relying on it into an accidental or lazy plagiarist and even increase the risk of being caught for cunning plagiarists.

Top Tips 2

4. Always be sensitive to cultural differences that may confuse students’ understanding of the plagiarism concept, especially those who are new to your country’s education system.

5. Encourage students to check with their tutor prior to submission as to whether they may have inadvertently broken (accepted) practice.

In any event, some allowances will have to be made where assignments must be written in a second or third language. This is not to condone wholesale plagiarism; simply to recognise that writing in a foreign language engenders a strong temptation to get linguistic assistance. Furthermore, given that some of the existing AI detectors have been found to frequently misclassify non-native English writing as being AI generated (see for example, Liang et al., 2023), it is important that universities consider the fairness and robustness of their academic misconduct procedures and be careful not to falsely accuse students of plagiarism.

Finally, it is also important that the department has a unified position about how to deal with and communicate about plagiarism. On the one hand, the message about plagiarism will be assimilated much faster if all academics use a common language and apply a similar approach on how to deal with plagiarism cases. On the other hand, coordination among academics will help come up with efficient prevention strategies by for example applying a progressive approach to deal with plagiarism (this might include, for example, teaching students about plagiarism by setting an intermediate formative assessment before the summative assessment or allow first year students to view the Turnitin’s Similarity Report before submitting the final version of their assessment – see section 2.3).

2.2. The motivations for plagiarism

To some, the increasing incidence of plagiarism in the higher education sector (see next section) may be looked upon as perfectly acceptable behaviour. According to author and satirist Stewart Home, plagiarism ‘saves time and effort, improves results, and shows considerable initiative on the part of the plagiarist’ (cited in Duguid, 1996). This line of thinking is predicated upon the notion that there is nothing sinister about the liberal use of other people’s ideas. To plagiarise is not to steal another’s property, it is simply about the spread of information and knowledge.

Indeed, prior to the eighteenth-century European Enlightenment, plagiarism was useful in aiding the distribution of ideas and, in this sense, can be said to be an important part of western cultural heritage, up to that point in time. One might argue further that, with the new social conditions that have emerged with the widespread use of ICTs, it has once again become an inevitable part of contemporary culture, although for rather different reasons (Critical Art Ensemble, 1994). Allied to this is the increasingly results-driven education system, with its associated league tables, as well as the increasingly difficult and competitive labour market conditions for graduates, resulting from the UK’s wider-access policy for higher education.

Taking a more sceptical view, if we accept that it is typically the academically weaker students who tend to engage in the various forms of plagiarism, it is unlikely that these individuals will, consciously or unconsciously, be part of any crusade to spread information and knowledge. On the other hand, as the statistics cited in the next section would tend to indicate, it cannot be just they who are indulging in unethical practice (unless the majority of students can be described as academically weak!). Why is it, then, that students are resorting to plagiarism in increasingly large numbers?

Irrespective of a student’s ability, pressure to plagiarise can emerge because of a variety of influences. These include, for example:

- poor time management skills (a problem often exacerbated because of the increasing competition for students’ time arising from the need to work part time or care for children) and an inability to cope with workload (perhaps as a result of class timetables and the corresponding multiple assessment tasks, with submission deadlines often bunched around the same date);

- a lack of motivation to excel because of a perception that the academic responsible for the class has little enthusiasm for the subject (the students then expending what they consider to be a commensurate amount of effort);

- increased external pressure to succeed from parents or peers, or for financial reasons;

- an innate desire to take on and test the system (particularly if the punishment associated with detection is relatively minor and/or the probability of detection is low);

- cultural difference in learning and presentation styles where, in some settings, it is considered normal custom and practice to quote the experts without citation (Campbell, 2017);

- Knowledge of other students engaging in cheating making them believe that cheating is not just acceptable (Awdry and Ives, 2021) but necessary as honesty will make students fall behind (The Times, 2023).

Top Tips 3

6. Ensure that assessment construction minimises the ease with which plagiarism can be both difficult to resist by the student and difficult for staff to detect (see section 2.5).

7. Be flexible in allowing extensions to deadlines if you are convinced that the only alternative would be to receive a plagiarised submission.

8. Overall, consider co-ordinating the timing of assignments in conjunction with other subjects, with a view to avoiding ‘peak loading’.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the factors that might be considered responsible for the frequency of plagiarism; suffice to say that it is an indicator of the complexity of the issue. Neither do these factors necessarily explain the increasing incidence of plagiarism.[3] Indeed, many, if not all, of those reasons listed above were in existence prior to the dramatic increase in the number of reported cases of plagiarism. The key explanatory variable, it would seem, is the increasing availability of electronic text. It is this, coupled with any of the above motivations that has spawned the seemingly inexorable rise in student plagiarism.

The spate of books on the subject, along with the various websites, media reports, conferences and symposia, is testimony to the amount of intellectual energy currently being dedicated to the topic of internet plagiarism. The major preoccupation is with both detection and deterrence: detection by resorting to ‘fighting fire with fire’ using various proprietary and freeware anti-plagiarism packages; deterrence through stressing the importance of education in ethics to ensure that students are not tempted to breach their university honour codes, and through the meting out of stiff penalties to offenders, to send a clear message that plagiarism is behaviour not to be tolerated in any circumstances.

2.3. A 'plagiarism epidemic'

If evidence is required of the alarming rise in the incidence of plagiarism, we just have to turn to some recent reports in the media. A 2016 article in The Times (2 January 2016) reported, in an investigation based on more than 100 freedom of information requests, that almost 50,000 students at British Universities were caught cheating over the previous three years. The article also reported a number of other important findings:

- Non-EU overseas students made a disproportionate number of the students caught cheating (Of the 70 universities that provided data from overseas students, those students were involved in 35% of all cheating cases but made up just 12% of the student body).

- The problem is not limited to undergraduate studies. Almost 20 PhD students (or equivalent) were disciplined for academic misconduct over the previous three-year period.

- 5 cases of impersonation were recorded at one university alone.

- Only about 1% of those found guilty of misconduct were dismissed because of cheating.

- “Freelance academics” charge anything from £10 to £20,000 for coursework answers, dissertations and even an ‘80,000-word PhD’.

This media article led to a very quick response by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA), the independent body that checks on standards and quality in UK higher education, with several policy documents produced in quick succession. First, in February 2016 the QAA Viewpoint alerted universities to the issue of ‘paper mills’ (QAA, 2016a). Then, in August, a full report on custom essay writing services was published on the issue (QAA, 2016b). Finally, in October 2017 the QAA produced a comprehensive guidance document for HE providers (QAA, 2017) which has since been updated (QAA, 2023b).

In the following years, The Times conducted new investigations on the incidence of plagiarism in UK Universities. In 2023, the newspaper found that academic malpractice among Britain’s most prestigious universities (21 out of the 24 Russel Group Universities) had more than doubled since the introduction of online exams caused by the Covid-19 pandemic (The Times, 2023). This is perhaps not surprising given that students believe that cheating is easier with online exams, especially those where students get to take it using their own electronic devices (Chirumamilla, Sindre and Nguyen-Duc, 2020).

This picture is clearly not limited to the UK. Newton (2018) while conducting a systematic literature review, found that contract cheating is increasing and that the percentage of students admitting paying someone else to undertake their work was 15.7%, which potentially represented 31 million students around the world.

It is also interesting to note that all students that looked at outsourcing their work did so by using paper mills and that only a small proportion of students that used paper mills submitted the received work as their own without making any changes. Awdry (2021) conducted an international survey in more than 11 countries and found that 7.4% of students reported using ‘formal outsourcing’ methods (e.g. use of paper mills, peer sharing sites, etc.) while 12.0% reported using ‘informal outsourcing’ methods (e.g. help from friends or family members). 51% of those using formal outsourcing methods reported that they used the received work for reference only, while 41% edited the work before submitting it. However, as many as 9% submitted the work as they received it.

An article by Rigby et al. (2015) developed the first empirical investigation of the decision to cheat by university students. They found that risk preferring students, those working in a non-native language, and those believing they will attain a lower grade are willing to pay more for an essay and hence are more likely to plagiarize. Furthermore, and perhaps not surprisingly, they also found that the likelihood of a student purchasing an essay and the amount a student is willing to pay for those essays decline as the probability of detection and associated penalty increase. This result partly explains the high incidence of plagiarism found in The Times (2016, 2023) articles. The fact that only 1% of the students caught cheating were expelled from their universities might lead students to believe that, in what concerns plagiarism, crime pays in the end.[4]

The high number of reported cases of plagiarism detected by universities are only made possible by the widespread use of plagiarism detecting software tools, the most widely used of which is Turnitin. Turnitin is a Web-based platform for management of assignments and feedback, with a built-in check for plagiarism and collusion. It compares each assignment with its database of “over 99 billion web pages, 1.8 billion student papers, and 89.4 million subscription articles”.[5] For that reason, it is a very effective and powerful tool to prevent collusion among students within the same university, the ‘recycling’ of parts or the totality of papers by students in different modules, students ‘sharing’ the same paper at different universities and the outright copy and paste plagiarism from materials available online.

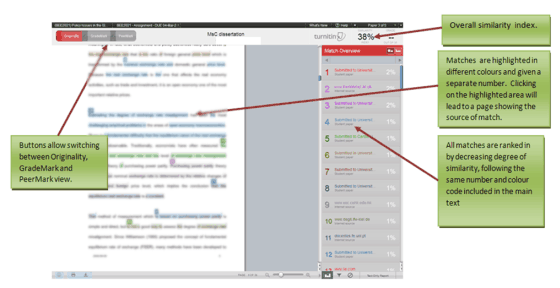

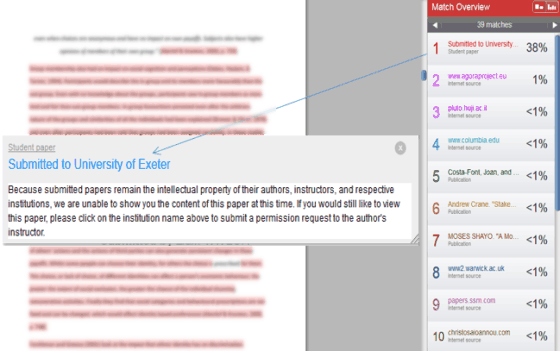

Figure 1 below shows an example of an originality report.

Figure 1: Example of originality report in Turnitin (click to expand)

Detecting plagiarism using Turnitin can be very time consuming and complex.[6] A high similarity score does not immediately imply that plagiarism or collusion was committed as it can be the result of the sum of many similarity matches of small, commonly used expressions. Another complication is that the software can be manipulated by students if they are allowed to see their similarity reports and resubmit their work by, for example, changing the occasional word in a sentence to make the software ignore the similarity. Allowing students to see the originality report in their work prior to submission can be a very useful tool to teach students about plagiarism as well as safeguard academic integrity but this is not without its dangers.

Figure 2 shows an example of plagiarism in Turnitin. Although many small similarities with other works are found, which is to be expected, there is one match that accounts for a very large amount of similarity (38%) and most of this comes from entire paragraphs being copied and pasted directly into the assignment. Further investigation (as well as proof of the plagiarism) can easily be made by clicking on each match on the match overview panel, which will take you to the original source of the text. Sometimes that source is not publicly available (e.g. paper submitted by a student at another university) and in these cases the academic will need to ask for permission from the author’s instructor to see the original paper.

Figure 2: Example of plagiarism in Turnitin

2.4. The tip of the iceberg? The 'Paper Mills' problem

Plagiarism detection, with software tools like Turnitin, is used widely at universities around the world and extremely useful in detecting what can be called ‘type-1 plagiarism’:[7] the act of copying and pasting materials available online. These applications seem impotent, however, to detect Type-2 plagiarism or the use of bespoke essay-writing services or ‘paper mills’ – businesses that make up arguably one of the most successful internet industries after pornography and gambling.[8] Indeed, as The Economist observed in the aftermath of the dotcom crash, these cheat sites are one of the few dotcom business models that continue to prosper (Anon, 2002) although the rise of Generative AI of late seems to be impacting the paper mills’ business model in a fundamental way (see section 4 below).

Some sites rely on advertising revenue and supply services free-of-charge or facilitate exchange (students submitting a paper and getting one in return). In most cases, however, it is fee-for-service. Students can purchase pre-written or commissioned papers, and while the format varies slightly from one operator to another, customers can pay anywhere from “several hundred pounds for a single essay to £6,750 for a PhD dissertation”. (Khomami, 2017).

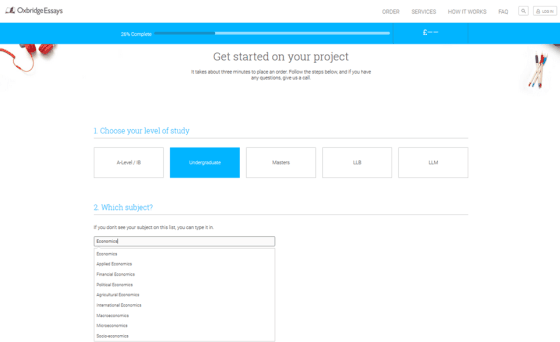

The most professional looking UK-based sites, like for example OxbridgeEssays.com or IvoryResearch.com, offer a very wide variety of products for students at every level of study.

Figure 3 below shows an example where clients can choose from different levels of study from A-Levels to Postgraduate studies (help with “PhD proposal, title creation or individual chapters” of a PhD dissertation are also available but require speaking to an ‘academic consultant’) and a drop-down menu choice of specialized topics within each discipline.

Figure 3: Booking a ‘Project’ (click to enlarge)

Although these types of companies invariably have a disclaimer that their products are “intended solely for the purpose of inspiring that client’s own work through giving an example of model research, writing, expression and structuring of ideas” (Oxbridge Essays terms and conditions, archived at archive.ph/JlHti), it is clear that the business model is directed at providing students with “100% original and plagiarism free” papers.[9]

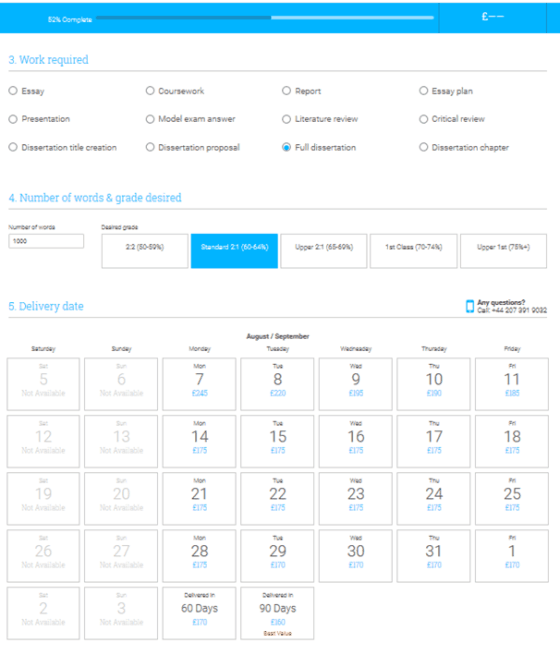

Figure 4 shows the options available to clients when booking a project. The variety of types of products is amazingly large and clients can buy bespoke pieces of work that include not just essays and full dissertations but also presentations, dissertation proposal, literature reviews, critical reviews, among others.

Clients can even specify what grade boundary they are after (from 2:2 to ‘Upper 1st’), chose the date of delivery in an airline-style booking site where prices change according to the date of delivery, have a ‘money back guarantee’ (e.g. EssaysMavens.co.uk offers a “100% money back guarantee”) and generous discounts (most companies offer regular discounts of up to 50%, while others like UKEssays.com provides up to 15% off for referring a friend).

The example presented in Figure 4, shows the prices for a full undergraduate dissertation, for a ‘standard 2:1 (60-64%) over a month period. Depending on the urgency prices over that period vary from £245 (3 days) to £160 (90 days). If the grade boundary is instead chosen to be ‘Upper 1st (75%+)’ the prices range from £525 (3 days) to £345 (90 days).

The providers link clients to writers that are recent graduates from the same or similar institutions or even a “network of some of the finest academic writers in the UK and beyond” (Oxbridge Essays "How it Works", archived at archive.ph/6RWoa) and therefore are very familiar with each university’s requirements for assessment.

Figure 4: Choosing a delivery date and a classification (click to enlarge)

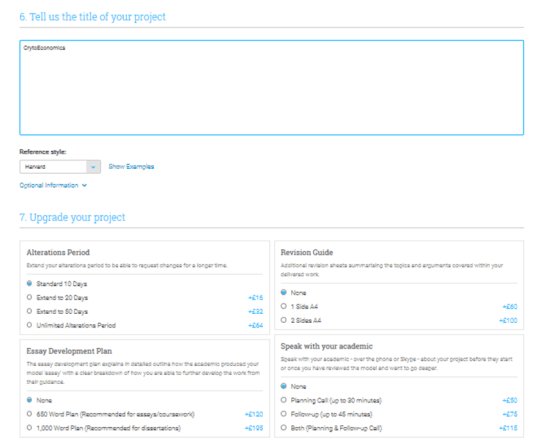

The service also typically includes ‘Upgrade Options’. Figure 5 shows an example where clients can ask for alterations (from a standard 10 days for an additional £16 to an unlimited alterations period for an additional £64), an ‘essay development plan’ that explains in detail “how the academic produced your model 'essay' with a clear breakdown of how you are able to further develop the work from their guidance.” A ‘revision guide’ is also available that provides “additional revision sheets summarising the topics and arguments covered within your delivered work”, all of which would, arguably, be invaluable if the client was asked to give a presentation or a viva.

Figure 5: Some Upgrade Options (click to enlarge)

While accurate statistics are not always easy to obtain given the dynamism of the industry, cursory perusal of the websites of the leading companies would suggest that, taken together, these sites are likely to receive visitor numbers running into millions each week. StudyMode.com (archived at archive.ph/whP8s) for example, a company founded in 1999 boasts that it is “self-funded and expanding daily, (…) serves more than 2 billion pages per year to students all over the world.”

The growth in this industry is surprising given the lack of guarantees clients get. If a client finds herself out of pocket because the company fails to supply the order or gets a grade that is lower than the one she paid for, it will be hard to complain without exposing herself as a cheat.

"[O]nline forums are full of complaints about essays arriving peppered with spelling mistakes, arguments that don't match pre-approved propositions and – the most common grievance – results that don't match the promised grade" (Potts, 2012).

Potts (2012) reports a case where a client did not receive her essay on time and was informed by the supplier that she could not get a refund but could claim a discount off the next purchase she made with them. The essay never arrived and she was £200 out of pocket.

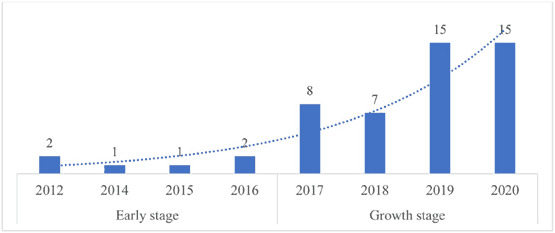

Given these developments, it is not surprising that a large volume of literature has emerged in the last few years focusing on the subject of plagiarism in the higher education sector. The rise of ‘paper mills’ seems to be increasing plagiarism to truly epidemic proportions, raising serious concerns among universities and governments. Figure 6 below illustrates the rapid growth, especially since 2017, in the number of articles with contract cheating as a research topic.

Source: Ahsan et al. (2022)

Figure 6: Evolution of research on contract cheating

The then UK universities minister Jo Johnson stated in 2017 that “this form of cheating is unacceptable and pernicious. It not only undermines standards in our world-class universities, but devalues the hard-earned qualifications of those who don’t cheat”. He urged the sector to implement “strong policies and sanctions to address this important issue in the most robust way possible”.[10]

In June 2019, the QAA then made the case for legislation to make the provision of contract cheating a criminal offense (QAA, 2019) and in April 2022, paper mills have finally been made illegal in the UK with the implementation of the Skills and Post-16 Education Act of 2022. This act now makes it a criminal offense to provide or arrange for another person to provide contract cheating services or to advertise contract cheating services. Although undoubtedly a step in the right direction, it remains to be seen how effective this ruling will be in preventing the use of paper mills.

2.5. Deterring and preventing 'Type-2' plagiarism

Various strategies can be employed by academics to police plagiarism, ranging from simple Web search techniques used by individual lecturers, to the employment of easy-to-use freeware capable of tracking plagiarism between cohorts of students, as well as to quite elaborate systemic approaches involving the engagement of commercial plagiarism detection companies as described in section 2.4.

Top Tips 4

9. Familiarise yourself with the various plagiarism detection software packages and develop an efficient rubric for checking your submissions.

10. Consider forming detection ‘teams’ with a view to providing an efficient division of labour and guidelines for best practice.

11. Remain open-minded at all times.

Detecting type-2 plagiarism, the production of bespoke essays by professional staff, is a much harder, time-consuming task and very difficult to prove in most cases. As discussed above, ‘paper mills’ employ experienced professionals (in fact, some paper mills boast having established academics working for them) to produce tailored and completely original work which for that reason is not detectable via the plagiarism detection software. Academics might find themselves reading assignments that are out-of-character for a specific student (because the quality of work is higher than the typical grades the student gets, or the assignment uses colloquialisms that are unlikely to be known of certain groups of students) but given that the academic has burden of proof, the punishment of this practice might not always be forthcoming.

This explains why in recent years, the attention seems to be turning to developing software applications that detect plagiarism through the use of stylometry – the application of the study of linguistic style to determine the authorship of (mostly written) works. Software applications that use stylometric analysis study measurable features of literary style, such as sentence length, vocabulary richness and use statistical tools to identify variations in the frequency of words, word lengths, word forms, that suggest different authorship and hence plagiarism. Although these products are still in a developing stage, academics are very hopeful that these applications will assist with the detection of completely plagiarized works, bought from paper mills.[11]

Top Tips 5

12. Create an explicit focus on learning outcomes – students need to see the point of what they are doing.

13. Design assessments that motivate students on the basis of the quality of their learning and the generic skills they acquire rather than the content they memorise.

14. Design assessments where the learning experience is truly authentic, suitably contextualised, completed within a suitably limited time period and as specific to the university course unit as possible.

15. Encourage students to role-play and ‘suspend disbelief’ in assignments, so that they develop a much greater empathy for the subject matter (Chancellor of the Exchequer, CEO, etc.).

16. Include the mandatory use of assignment cover sheets that incorporate signed declarations of originality.

17. With an assignment that is to be submitted electronically, use pop-up confirmations about the conditions that a student is agreeing to when they upload their assignment.

While most universities around the world rely on their publicly stated policies and procedures (including honour codes and student contracts) to act as a deterrent to any student contemplating plagiarism, their publication alone is unlikely to cut any sway with would-be plagiarists. Even universities that are committed to eradicate plagiarism must be aware that approaches that “focus on eradication rather than minimisation of plagiarism can be impractical, prohibitively expensive and even harmful to the learning environment” (QAA, 2017).

Given that chances of detection of type-2 plagiarism are painfully low (and the rate of punishment being even lower – see section 2.3), the way to avoid type-2 plagiarism must be through prevention.

Prevention may be associated with the creation of an environment where students never feel motivated to plagiarise or where engaging in plagiarism becomes very costly and extremely difficult, making it a less attractive practice to engage on.

The ability to analyse problems critically is not in abundance among those who elect to plagiarise material from the internet or from their peers, and as the discussion in the sections above demonstrates, the policing of this kind of activity can be a time-consuming and expensive business.

Formal tuition in the art of critical thinking is certainly a way forward, but this will not be time well spent if, subsequently, students are not presented with adequate opportunity to apply this important generic skill. All too often, assignments and examination questions are set that encourage the reproduction of content knowledge rather than critical appreciation of that content knowledge. Generally speaking, this tends to be a reflection of module design that is driven primarily by content considerations and where assessment is very much of an afterthought, rather than the other way around. In short, to be effective, assessment must be authentic: it must mean something to the student, so it will engage them and add value to their skill set.

As scholars such as Ramsden (1992) have argued, the quality of students’ understanding is intimately related to the quality of their engagement with learning tasks. Setting tasks that test their memories or their ability to reproduce content material is not particularly engaging, and this is precisely what many assessment items require – the same assessment items that, coincidentally, lend themselves very well to cutting-and-pasting techniques.

Top Tips 6

18. Exercise a firm commitment to authentic assessments that have the effect of minimising the extent of assignment recycling, even to the point where every assessment item is unique.

19. Use a mixture of assessment methods and develop novel, employer-focused types of assessment (e.g. policy briefs, executive summaries, video presentations, etc).

20. Seek to encourage departmental co-ordination in a commitment to authentic assessment as a strategy to combat student plagiarism. In this way, students can see there is a synchronised departmental effort to change the way that learning is assessed, and that there is consistency of treatment when it comes to meting out penalties for plagiarism offences.

A pertinent question to ask is whether students are entirely to blame for the plagiarism problem that plagues our universities. The study conducted by Ashworth et al. (1997) would suggest not. They conclude that cheating might be looked upon as a symptom of some general malaise. They found that students felt alienated from teaching staff because of their demeanour and their lack of contact with students. Assessment tasks that fail to engage students are a symbol of this gap between students and lecturers, and in the absence of any basic commitment on the part of the student that the work they are doing is significant, there is no moral imperative to refrain from plagiarism or cheating.

The point is that while one cannot ‘turn a blind eye’ to students’ plagiarism, it would be fatuous to assume that it is the students who are at fault and the students alone. Could it be that students are cheating because they do not value the opportunity of learning in university classes? Is it conceivable that the pedagogy currently employed has not adjusted to contemporary circumstances? As one author has observed, ‘we expect authentic writing from our students, yet we do not write authentic assignments for them’ (Howard, 2002). It is worth considering why this might be so: one argument is that the ever-increasing pressure on academics to teach, research and administer reduces the time for creating imaginative and otherwise difficult-to-plagiarise (for example, individualised) assignments. As a consequence, there is much anecdotal evidence that academics are retreating back to the unseen, written examination as the sole method of assessing student performance in their courses.

As the literature on authentic assessment reveals, it is solidly based on constructivism, and acknowledges the learner as the chief architect of knowledge building (see, for example, Herrington and Herrington, 1998). It is a form of assessment that fosters understanding of learning processes in terms of real-life performance as opposed to a display of inert knowledge. The student is presented with real-world challenges that require them to apply their relevant skills and knowledge, rather than select from predetermined options, as is the case with multiple-choice tests, for example. Importantly, it is an approach that engages students because the task is something for which they will have an empathy, which, as the empirical evidence suggests, elicits deeper learning.

Top Tips 7

21. Make it a requirement of assessment submissions that outlines and first drafts be submitted on specified dates in the lead-up to the final submission date. This means that the process of producing an assignment is evaluated as well as the final product (Carroll, 2002). This may not prevent some students copying from one another along the way, but it will thwart those individuals who look to produce the finished product while doing very little work themselves.

22. Require students to submit a reflective journal describing their approach to the task, the methodology adopted, the problems encountered and how they resolved these problems.

23. Hold random viva voce sessions that require students to defend and further explain, if necessary, what they have written. If this is clearly advertised to students in class and in course documentation, it will serve as an effective deterrent.

The key, therefore, is to set meaningful, situational questions relating to real-life, contemporary problems that engage students in the learning process. By making assignments as module-specific as possible - to prevent students from purchasing pre-written papers or paying outsiders to write answers and by the examiners making it clear (as a stated objective of the module unit) that they are looking to reward evidence of depth of learning and sound critical analysis rather than recall of content knowledge - assignments are effectively cheat-proofed, although we must always be mindful of the increasing resource constraints placed upon academics.

Something of a paradigm shift is likely to be required if the changes described above are to be readily embraced by the majority of teachers in the higher education sector. However, it is worth mentioning that the various ICTs, if used effectively, may well assist in this endeavour. Indeed, one could make the point that if as much energy and ingenuity went into developing new and exciting online devices for the purposes of facilitating assessment as there have been devoted to online devices for the detection of plagiarism, then maybe there would be fewer obstacles to negotiate.

In summary, while there is clearly a need to allocate some resources to detection and deterrence, these are essentially reactionary strategies with low probability of success. The proactive measure is the prevention of plagiarism through innovative pedagogy, as this is more likely to produce lasting results. Such an approach provides students with an incentive to learn. The natural corollary to this is that there will be less incentive for students to resort to plagiarism.

↑ Top3. The Covid pandemic and the sudden move to online assessments

The emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020 and the measures and lockdowns that followed in the next 18 months or so, forced universities to move their teaching and assessment online with very little warning or time to prepare for such a drastic change.

The move from face-to-face teaching and assessment to an online format created new challenges and disruptions, as well as new opportunities, across the higher education sector.

When higher education institutions closed their physical doors around March 2020, university administrations moved first teaching and then assessment online. Most universities tried to mitigate the potential negative impact on students in several ways.

The most common response by universities was to move assessments that had been designed to be taken in person to an online, open-book format, with extended time limits. The duration applied to each assessment varied greatly across universities, but it was not uncommon that a final exam that had originally been planned to have a 2h duration, was extended to a much larger window, sometimes up to 24h.

Universities also introduced new ‘no-detriment’ policies and other mitigating measures to try and minimize the negative impact of the new reality on student outcomes. For many higher education providers, the no-detriment policy meant that students were guaranteed that their final grade was not lower than their average academic performance before Covid struck. Other measures included, according to Chan (2023), a binary grading system (i.e. pass/fail), relaxed progression policies, revised extension/deferral/exceptional circumstances policies and mark adjustments (scaling of grades).

Whilst the move to online assessment with massively extended time limits clearly made academic misconduct easier, the introduction of the variety of the other mitigation policies described above, should have reduced the incentive to cheat. The obvious question to ask is which of these conflicting forces dominated? Did plagiarism increase or decrease with the rapid and generalized move to online assessments?

Several recent papers clearly suggest that plagiarism and other forms of academic misconduct like collusion and the use of essay mills got much worse after Covid. A recent systematic review of the literature by Newton and Essex (2023), for example, established that self-reported online exam cheating jumped to 54.7% during Covid compared with a the Pre-Covid level of 29.9%. They also found that individual cheating was more common than group cheating, and the most common reason students reported for cheating was simply that there was an opportunity to do so.

Janke et al. (2021) found a similar pattern in Germany where students reported cheating much more often during online than face-to-face exams. Lancaster and Cotarlan (2021) looking at one essay mill in particular (Chegg.com) found that contract cheating went up by almost 200% in five STEM subjects after Covid.

These results should give universities food for thought.

Having discovered the benefits of online assessments (notably in terms of costs), many university administrations are pushing very strongly for the wider use of online assessments and opposing the return to face-to-face exams that were common in the pre-Covid era.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the push for more online assessment is also very popular with students. Students prefer to do online exams from the comfort of their homes without having to spend time and money travelling to complete an assessment. They also like the increased flexibility an online exam brings, lower time pressures, not having to commit large parts of the content to memory and the possibility of correcting errors before submitting their answers.

However, given the rise in academic misconduct, “future approaches to online exams should consider how the basic validity of examinations can be maintained, considering the substantial numbers of students who appear to be willing to admit engaging in misconduct” (Newton and Essex, 2023). Thus, universities will need to “ramp up remote proctoring, use more in-person exams and change the structure of exam questions to make it harder to cheat” (Lem, 2023). At the same time, as discussed above, universities must also move further towards authentic assessments, where students must apply their skills to real-life situations, as a general strategy to reduce the willingness of students to engage in plagiarism.

↑ Top4. The rise of Generative AI

Academics had barely had time to adapt their assessments to online delivery and to get used to the term ‘non-googleable question’ when the release of the Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT) in November 2022 signalled the emergence of an even more profound change.

ChatGPT is a generative AI[12] that has demonstrated a remarkable ability to summarize information and to hold human-like conversations. ChatGPT browses the internet for updated information and considers the entirety of the user’s prompts to deduce context and provide a personalised answer.

The technology is not without its critics but it has proven more than capable of passing exams in various disciplines, including economics (OpenAI, 2023). In the Test of Understanding of College Economics (TUCE), an exam consisting of 30 multiple choice questions with four answer choices each, ChatGPT ranked in the top 9% and 1% among the exam takers that year in Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, respectively (Geerling et al., 2023).

This ability immediately led the technology to be seen as an “existential threat” to universities and not long after its release, cases of plagiarism started to emerge. Prof. Darren Hudson Hick of Furman University, for example, posted on Facebook two weeks after the release of ChatGPT that he had referred a plagiarising student who used it to write their essay.

It is important to note, however, that this is not the first time that a new technology got educators worried. Similar concerns were raised when calculators, spell checkers, Google, and Wikipedia, just to name a few, came out (Lindsay, 2023; Surovell, 2023). Universities adapted then and nowadays the use of these technologies is commonplace in education and the same will surely eventually happen with generative AI.

Interestingly, not everyone agrees that the use of AI tools constitutes academic misconduct. Anders (2023) argues that using ChatGPT is not cheating. First, because it is freely available to everyone and as such no individual student will gain an unfair advantage over others by using it. Second, plagiarism is defined by universities as “improperly representing another person’s work as their own” and this definition does not apply to machines like ChatGPT.[13]

However, most academics and university administrations tend to see the use of ChatGPT and other AI tools (without acknowledgement) a clear case of academic misconduct. Harte and Khaleel (2023), for example, argue that using ChatGPT is an academic misconduct, but also that it merely represents a technological advancement on an already present risk. We should not forget that students can already engage essay mills to complete their assignments. ChatGPT simply reduces the cost and the delivery time without representing a new risk to academic integrity.[14]

Caulfield (2023) reviewed in August 2023 the guidelines on the use of AI writing tools of 100 UK universities listed in the Times Higher Education rankings for 2023 and was unable to find a clear guidance or policy for 61% of them.

Eventually all universities must decide how to respond. Lindsay (2023) indicates four main strategies universities can follow in their response to generative AI:

- Ban it: Caulfield (2023) found that that a minority of universities (17%) either banned the use of AI writing tools or banned them by default unless instructors allow their use in their modules. Given the rapid development and ubiquity of AI tools, trying to ban it is likely to turn out to be an impossible task. Moreover, not teaching AI literacy to students will be counterproductive and could decrease their chances to find employment. AI tools may not be reliable enough anytime soon to replace doctors, for example, but “doctors who use AI will replace doctors that don’t” (Fayyad, 2023).

- Return to in-person exams: A popular response among academics does not ban the use of AI tools explicitly but instead aims to create assessments where students are unable to use them. Pirrone (2023), for example, recommends that oral and classroom assessments should be favoured instead of take-home assessments. His main argument is that AI technology is intrusive and damaging and resisting it rather than embracing it is in the interest of students. However, proctoring in-person exams requires financial resources and pose considerable operational challenges to universities (Lindsay, 2023).

- Develop AI literacy: Caulfield (2023) found that 12% of the universities allowed the use of AI writing tools (with proper citation) unless instructors disallow their use in their modules. Dickinson (2023) recommends that instead of focusing on student’s output, assessments should reward their contribution. Students should be free and even encouraged to use AI writing tools to develop their AI literacy skills, but their mark should be determined by their own contribution. This of course assumes that students honestly disclose and reference the AI’s contribution in their work. This also necessitates that universities create policies on and educate students about the ethical and constructive use of AI writing tools (Ple, 2023).

- Assess ‘humanness’: Educators can create assessment with the question “what are the cognitive tasks students need to perform without AI assistance?” in mind (Lindsay, 2023). There are certain tasks, like demonstrating higher-order thinking (Geerling et al., 2023), reflecting on experience within a module (Harte and Khaleel, 2023), or solving ‘authentic assessments’ where students use and apply knowledge and skills in real-life tasks, that AI tools are not particularly good at.

Regardless of what strategy a university follows, (apart from relying solely on in-persons exams) an important safeguard is the ability to detect AI generated content and to be able to separate it from the contribution of the student.

At the time of writing, the most commonly used plagiarism detectors are not very good at detecting AI generated content. Several tools are being developed specifically to detect content generated by AI writing tools; Turnitin, for example, has released a preview of its AI detection tool in January 2023 just weeks before OpenAI announced the development of its own AI classifier.

Weber-Wulff et al (2023) tested 14 of these detectors, 12 of which are freely available and 2 are commercial products. They found that these tools incorrectly identify a human written text as AI generated on average in 2.4% of the cases. This leaves room for a very large number of false positives that need to be investigated and shows that universities need to be very careful when relying on these tools. Sokol (2023), for example, describes the cautionary tale of a first-year undergraduate whose essay was falsely flagged by Turnitin for using AI. Weber-Wulff et al. (2023) also found that these tools incorrectly flag as AI written a text written by a human in a non-English language that is translated to English by AI on average in 11.1% of the cases and that AI generated text went undetected in a significant number of cases: 20.6% for texts fully generated by AI, 51.6% for AI generated text with human manual edits, and 71.6% for AI generated texts paraphrased by AI.

Most experts show little faith that AI detectors will ever be able to detect AI generated content with a high degree of accuracy. In fact, OpenAI has announced in July 2023 that it's shutting down its AI detector due to poor performance. Even if good AI detectors are developed in the future, the rapid speed of change in AI tools is likely to make those detectors outdated very quickly.

↑ Top5. Final remarks

This chapter focused on defining the characteristics of plagiarism and establishing how it manifests itself in the current university environment. It discussed the main factors deemed responsible for plagiarism and the mechanisms employed by universities to deal with its increasing incidence, especially in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and the recent emergence of generative AI technology.

We demonstrated that focusing on detection alone, although necessary and important, is unlikely to solve the problem and that prevention is much more likely to yield lasting results. Detection and deterrence of plagiarism cannot be the sole focus of universities as it is essentially a reactionary approach, one that is unlikely to yield long lasting benefits and might not be efficient in stamping out the most serious and sophisticated forms of plagiarism that are constantly evolving.

The proactive approach is to focus on the prevention of plagiarism through a department-wide coherent use of innovative pedagogy and authentic assessments, one that present students with real-world challenges that require them to apply their skills, knowledge, critical analysis and that engages students in the learning process rather than focusing on content regurgitation that leads to an increased incentive to use essay mills or generative AI and does not develop the student’s employability skills.

↑ Top6. Further reading

Austin, M. and Brown, L. (1999) "Internet Plagiarism: developing strategies to curb student academic dishonesty", The Internet and Higher Education, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 21-33. DOI 10.1016/S1096-7516(99)00004-4

Bannister, P. and Ashworth, P. (1998) "Four good reasons for cheating and plagiarism", in C. Rust (ed.), Improving Student Learning Symposium, Centre for Staff Development, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Carroll, J. (2002) A Handbook for Deterring Plagiarism in Higher Education, OCSLD, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Furedi, F. (2001) "Cheater's Charter", Times Higher Education Supplement, 8 June 2001.

Harris, R. A. (2001) The Plagiarism Handbook: Strategies for Preventing, Detecting and Dealing with Plagiarism, Pyrczak Publishing, Los Angeles, CA.

Herrington, J. and Herrington, A. (1998) "Authentic assessment and multimedia: how university students respond to a model of authentic assessment", Higher Education Research and Development, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 305–22. DOI 10.1080/0729436980170304

Lathrop, A. and Foss, K. (2000) Student Cheating and Plagiarism in the Internet Era: A Wake-up Call, Libraries Unlimited, Englewood, NJ.

Moon, J. (1999), "How to stop students from cheating", Times Higher Education Supplement, 3 September 1999.

Newton, P. and Lang, C. (2016) "Custom Essay Writers, Freelancers, and Other Paid Third Parties", in T. Bretag (ed.) Handbook of Academic Integrity, Singapore: Springer Singapore, pp. 249–271.

Oblinger, D., Groark, M. and Choa, M. (2001) "Term paper mills, anti-plagiarism tools, and academic integrity", Educause Review, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 40–8.

Park, C. (2003) ‘In other (people’s) words: plagiarism by university students – literature and lessons’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 471–88. DOI: 10.1080/02602930301677

QAA (2023a): Maintaining quality and standards in the ChatGPT era: QAA advice on the opportunities and challenges posed by Generative Artificial Intelligence, Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, 8 May 2023

Wiggins, G. (1990) ‘The case for authentic assessment’, Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, vol. 2, no. 2. DOI: 10.7275/ffb1-mm19

↑ TopReferences

Ahsan, K., Akbar, S. and Kam, B. (2022) ‘Contract cheating in higher education: a systematic literature review and future research agenda’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47:4, pp. 523–539, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1931660

Anders, B. (2023) "Is using ChatGPT cheating, plagiarism, both, neither, or forward thinking?", Patterns, 4(3), DOI: 10.1016/j.patter.2023.100694

(2002) "Plagiarise: let no one else’s work evade your eyes", The Economist, 14 March.

Ashworth, P., Bannister, P. and Thorne, P. (1997) "Guilty in whose eyes? Ashworth University students’ perception of cheating and plagiarism in academic work and assessment", Studies in Higher Education, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 187–203. DOI: 10.1080/03075079712331381034

Awdry, R. (2021) "Assignment outsourcing: moving beyond contract cheating", Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46:2, pp. 220–235, DOI: 10.180/02602938.2020.1765311

Awdry, R. and Ives, B. (2021) "Students cheat more often from those known to them: situation matters more than the individual", Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 46, no. 8, pp. 1255–1269. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1851651

Campbell, A. (2017), "Cultural Differences in Plagiarism", The Turnitin Blog, 20 December.

Carroll, J., (2002), "A Handbook for Deterring Plagiarism in Higher Education", OCSLD, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Caulfield, J., (2023), "University Policies on AI Writing Tools: Overview & List", Scribbr, published on 12 June (revised on 16 August), accessed: 2 October 2023.

Chan, C. K. Y. (2023), "A review of the changes in higher education assessment and grading policy during covid-19", Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48:6, pp. 874–887. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2022.2140780

Chirumamilla, A., Sindre, G. and Nguyen-Duc, A. (2020), "Cheating in e-exams and paper exams: the perceptions of engineering students and teachers in Norway", Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45:7, pp. 940–957. DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1719975

Critical Art Ensemble (1994), "Utopian Plagiarism, Hypertextuality, and Electronic Cultural Production", (accessed 12 June 2004).

Dickinson, Jim (2023), "An avalanche really is coming this time", Wonkhe, Comment, 17 March 2023.

Duguid, B. (1996), "The unacceptable face of plagiarism?" (accessed 12 June 2004).

Fayyad, U. (2023), "Stochastic Parrots Or Intelligent Assistants?", Forbes, 6 January.

FT (2023), "Education companies’ shares fall sharply after warning over ChatGPT", Financial Times, 2 May 2023.

Geerling, W., Mateer, G. D., Wooten, J., & Damodaran, N. (2023), "ChatGPT has Aced the Test of Understanding in College Economics: Now What?", The American Economist, 68 (2), pp. 233–245, DOI: 10.1177/05694345231169654

Harte, P. and Khaleel, F. (2023), "Keep calm and carry on: ChatGPT doesn't change a thing for academic integrity", Times Higher Education, 13 March.

Herrington, J. and Herrington, A. (1998), "Authentic assessment and multimedia: how university students respond to a model of authentic assessment", Higher Education Research and Development, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 305–22. DOI 10.1080/0729436980170304

Howard, R. M. (2002) "Don’t police plagiarism: just teach!", Education Digest, vol. 67, no. 5, pp. 46–9.

Hudson Hick, D. (15 December 2022) "Today, I turned in the first plagiarist I’ve caught using A.I. software..." (Facebook post) Archived from the original at https://archive.ph/uSECk

Janke, S., Rudert, S., Petersen, A., Fritz, T. and Daumiller, M. (2021), "Cheating in the wake of COVID-19: How dangerous is ad-hoc online testing for academic integrity?", Computers and Education Open, Vol. 2, DOI: 10.1016/j.caeo.2021.100055.

Khomami, N. (2017) "Plan to crack down on websites selling essays to students announced", The Guardian, 21 February (accessed 4 August 2017)

Lindsay, K. (2023), "ChatGPT and the Future of University Assessment", Kate Lindsay Blogs, 16 January 2023, accessed 27 September 2023.

Lancaster, T. and Cotarlan, C. (2021), "Contract cheating by STEM students through a file sharing website: a Covid-19 pandemic perspective", International Journal of Educational Integrity, 17, 3. DOI: 10.1007/s40979-021-00070-0

Lem, P. (2023), "Majority of students cheat in online exams – study", Times Higher Education, News, August 17.

Liang, W., Yuksekgonul, M., Mao, Y., Wu, E. and Zou, J. (2023), GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers, Patterns, vol. 4, Issue 7. DOI: 10.1016/j.patter.2023.100779

Newton. P. M. (2018) ‘How Common Is Commercial Contract Cheating in Higher Education and Is It Increasing? A Systematic Review’, Frontiers in Education, vol. 3. DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00067

Newton, P. M. and Essex, K. (forthcoming), "How Common is Cheating in Online Exams and did it Increase During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Systematic Review", Journal of Academic Ethics, pp. 1–21. DOI: 10.1007/s10805-023-09485-5

OpenAI (2023): GPT-4, 14 March, online at https://openai.com/research/gpt-4, accessed 27 September 2023.

Pirrone, A. (2023), "Resist AI by rethinking assessment", LSE Higher Education Blog, 23 March 2023, accessed 2 October 2023.

Ple, L. (2023), "Should we trust students in the age of generative AI?", The Times Higher Education Blog, 23 September.

Potts, M. (2012) "Who writes your essays?", The Guardian, 6 February (accessed 15 December 2017)

QAA (2016a), QAA Viewpoint - Plagiarism in UK Higher Education, February.

QAA (2016b), "Plagiarism in Higher Education - Custom essay writing services: an exploration and next steps for the UK higher education sector", August.

QAA (2017), "Contracting to Cheat in Higher Education - How to Address Contract Cheating, the Use of Third-Party Services and Essay Mills", October, online at http://www.qaa.ac.uk/publications/information-and-guidance/publication/?PubID=3200

QAA (2019), "Essay Mills and the Case for Legislation", June.

QAA (2023b): Contracting to Cheat in Higher Education – How to Address Contract Cheating, third edition.

Ramsden, P. (1992) Learning to Teach in Higher Education, Routledge, London.

Renard, L. (1999) "Cut and paste 101: plagiarism and the net", Educational Leadership, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 38–42.

Rigby, D., Burton, M., Balcombe, K., Bateman, I. and Abay Mulatu (2015), "Contract cheating & the market in essays", Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, vol. 111, pp. 23–37. DOI: 10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.019.

Shearing, H. and McCallum, S (2023), "ChatGPT: Can students pass using AI tools at university?", BBC News, Young Reporter, 9 May.

Smith, D. (1999) "Supervising NESB students from Confucian educational cultures", in Y. Ryan and O. Zuber-Skerritt (eds), Supervising Postgraduates from Non-English-speaking Backgrounds, SRHE and Open University Press, Buckingham.

Sokol, D. (2023), "It is too easy to falsely accuse a student of using AI: a cautionary tale", The Times Higher Education Blog, 10 July

Surovell, E. (2023), "ChatGPT has everyone freaking out about cheating. It’s not the first time.", The Chronicle of Higher Education, 8 February.

The Times (2016) "Universities face student cheating crisis", 2 January.

The Times (2023) "Cheating at universities doubles since the start of online exams", 17 February.

Weber-Wulff, D., Anohina-Naumeca, A., Bjelobaba, S., Foltýnek, T., Guerrero-Dib, J., Popoola, O., Šigut, P. and Waddington, L. (2023), "Testing of Detection Tools for AI-Generated Text". arXiv, 10 July, arXiv:2302.15666.

↑ TopFootnotes

[i] The usual disclaimer applies.

[1] Many universities now require students to sign ‘student contracts’ that include specific regulations on cheating, collusion and plagiarism. For example see the University of Leeds student contract webpage http://students.leeds.ac.uk/studentcontract.

[2] When academics set a Turnitin assignment (see section 2.3), they can set a threshold minimum number of words to be picked up by the similarity report. Setting a high limit (say 7 words) will exclude a large number of sentences that are not of sufficient length from being considered in the similarity report making it much easier and faster to interpret the results.

[3] It is worth mentioning that the development of online detection tools like Turnitin is likely to also have contributed for the rise in the frequency in the detection of plagiarism cases.

[4] The Times (2023) report results of a recent poll that found that one in six students admitted cheating during online exams and of those only 5% said they were caught doing it.

[5] Source: http://www.turnitinuk.com/en_gb/features/originalitycheck/content

[6] Turnitin has introduced a new system, which they called ‘Feedback Studio’. Although the layout changed slightly with the introduction of ‘layers’, the functionalities available remain the same.

[7] The terms type-1 and type-2 plagiarism were assigned to Geoffrey Alderman of the University of Buckingham in The Times (2016) article.

[8] Paper mills are also interchangeably known as term paper mills, essay mills and essay factories and the act of using paper mills is sometimes called contract cheating and assignment outsourcing.

[9] Buy Essays dedicates an entire page to discuss whether using their service is cheating: "If you are wondering if using our essay writing service amounts to cheating or if its [sic] a good idea and you can get caught, we can assure you it is NOT cheating and there is no reason you will get caught. NONE of the customers we have written essays for has EVER been caught." It is interesting that they feel necessary to discuss the possibility of being caught despite that they do not consider using their services cheating.

[10] https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2017/10/09/education-in-the-media-9-october-2017/

[11] Software applications that use stylometry to detect plagiarism include JGAAP, AICBT and Signature.

[12] A generative AI is “a type of artificial intelligence system capable of generating text, images, or other media in response to prompts” (Wikipedia).

[13] It is important to note that many universities have since adapted their definition of plagiarism so that the offense of misrepresenting someone else’s work as the student’s own now includes AI-generated content too.

[14] Investors seem to agree with Harte and Khaleel (2023) that ChatGPT is a potential alternative to essay mills. Chegg's shares fell by 25% due to the introduction of ChatGPT (FT, 2023).

↑ Top