Based on the "LSE Handbook for Graduate Teaching Assistants" by Kate Exley and Liz Barnett, Teaching and Learning Centre, LSE, and "Small Group Teaching in Economics" by Caroline Elliott, Aston University and Christian Spielmann University of Bristol.

Edited by Dimitra Petropoulou, LSE and Martin Poulter, the Economics Network

This version published January 2020

The purpose of this handbook is to provide Graduate Teaching Assistants with practical information and insight into teaching. It includes some basic tips and suggestions on planning, preparation and delivery of small-class teaching, particularly aimed at newcomers to the profession.

1. Introduction

Current research clearly suggests that effective learning happens when students construct their own knowledge in an engaging environment. What makes small group teaching special is that it lends itself to interactive and student-centred teaching and thus has the potential to be an incredibly effective mode of instruction, when appropriate teaching approaches are adopted. Nevertheless, economics small group seminars are often front-led, with the teaching assistant focused on working through a problem set rather than on students’ process of understanding the material. This chapter shows how to make these sessions student-centred and engaging so as to facilitate the effective learning of economics.

2. How students learn

“Learning takes place through the active behavior of the student: it is what he does that he learns, not what the teacher does.”

Tyler (1949) just rephrases the old adage that we learn best by doing. This idea is the basis for all constructivist learning theories (see particularly Piaget (1950) and Bruner (1960, 1966)), which essentially suggest that learning happens when students ‘construct knowledge with their own activities’ (see Biggs, 2007, p. 22). A tutor’s role is not merely to present knowledge, but to create an environment where the student can truly engage with the material.

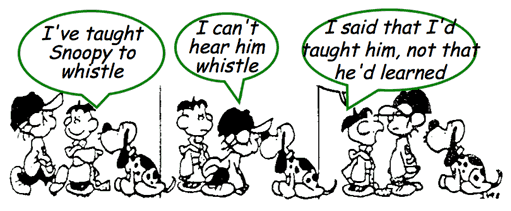

Far too often, tutors think that just because they "went through" the material, students will have grasped those concepts and be able to apply what has been taught. However, this is not necessarily true.

Figure 1

Biggs (2007) identifies different learning activities that can be implemented in small groups. In a small group, there is the possibility for effective use of class discussions, games and experiments, think-aloud tasks, role play, research projects, presentations or collaborative group work. Such activities put students in charge of their own learning.

Research suggests that when students create knowledge themselves, retention rates are much higher. The so called ‘learning pyramid’ matches retention rates to different learning activities. Sousa (2006) ranks different learning modes according to their average retention rates after 24 hours:

- lectures (5%),

- reading (10%),

- Audiovisual (20%),

- Demonstration (30%),

- Discussion Group (50%),

- Practice by Doing (75%), and

- Teach Others (90%).

While the educational literature still debates the validity of these estimates, there is a general consensus about the effectiveness of participatory teaching methods.

Activities with higher retention rates are ones that engage the student to construct new knowledge, for example through reflection, hypothesizing, explaining and arguing, thereby facilitating so-called deep learning. Enabling deep learning is a key aim for a successful tutor. Figure 2 orders some learning activities in their relation to deep and surface learning.

Figure 2: Bigg’s Adjectives to Describe Cognitive Engagement (from Biggs, 2007)

Small groups ideally lend themselves to activities which facilitate deep learning and which can create a constructivist learning experience. Table 1 is an overview:

| Suggestions for small and medium sized group sessions | Activities |

|---|---|

Working in pairs

|

|

Working in threes

|

|

| Working in fours or fives |

|

| ‘Pyramid’ or ‘snowball group’ (combining groups or adding individuals to groups one-at-a-time) |

|

| ‘Fishbowl’ (the ‘fish’ discuss an issue, while outside observers note criteria used etc.) |

|

| ‘Envoys’ or ‘crossover groups’ |

|

| Formal debate (four speakers, formal debate rules, contributions from floor, vote at the end, possibly vote at beginning also and then two votes compared) |

|

| ‘Your witness’ (modelled on Radio 4 programme) |

|

| Quiz show (individuals or preferably in teams) |

|

| Presentation with primed respondents |

|

| Role playing |

|

| Game, simulation or experiment (there are many games or simulation exercises available) |

|

| Computer lab session (using instructional software, such as WinEcon, or using data sets and/or statistical packages: see Economics Network site for details of software) |

|

| Virtual seminar (distance-based learning, using chat room facilities of a virtual learning environment/conferencing system, such as Blackboard or Moodle: students contribute from a terminal on site or at home) |

|

| Video (preferably not longer than 20 minutes) |

|

While implementing many of these activities may seem daunting at first, they are likely to improve student learning immensely. In addition, they are fun both to organise and perform in the classroom.

3. How to approach small group teaching

- 3.1 The role of the teaching assistant

- 3.2 The first session

- 3.3 Planning a session

- 3.4 Teaching question-based problem sets

- 3.5 Revision classes

3.1 The role of the teaching assistant

“Teachers should guide without dictating and participate without dominating.”

C.B. Neblette

It is often tempting to plan a small group teaching session where the onus is always on the tutor: maybe to revisit material covered in large group teaching sessions and then to provide answers to problem set, or to even ‘lecture’ new material to the students. In fact, if we always talk, there may also be less risk of students asking challenging questions.

As highlighted elsewhere in this chapter, students may also be temporarily relieved that the onus is not on them. However, they are highly unlikely to engage properly with the material taught in such a tutorial. In a session that facilitates deep learning, the role of the tutor is instead to organise and facilitate discussion and learning, as well as, hopefully, to inspire students. One way to do this is to demonstrate to students what fascinated you in economics, motivating you to teach and research the subject.

Tutors need to plan activities that make students responsible for learning. These may be discussions, group work, student presentations and many more, which we discuss throughout this chapter.

A recurring theme of this chapter is that to facilitate interaction and learning requires careful planning. Activities and stimuli for the students should be planned, but at the same time sufficiently flexible to accommodate the students’ learning journey. This is hard to do while preserving the overall coherence of the session. In this sense, your role is that of a moderator who guides and structures the students’ learning journey. Delivery of new material, if it has to occur, should not be the principal focus of the tutorial.

The tutor’s role is incredibly important. For students to willingly engage, they must feel at ease contributing. The tutor’s role extends to providing helpful comments and suggestions, encouraging students to work effectively with their peers. This might require the tutor to take the lead initially and then step back to facilitate student discussion and contributions. The objective is for students to have the confidence to ask questions, not only of the tutor, but of each other, and of the economics discipline. The tutor’s role is certainly not easy, but it can be immensely rewarding.

Finally, tutorials are ideal for fostering students’ transferable skills, including the ability to think critically, work effectively in small groups, or to present and articulate their ideas. The lack of such skills is a recurring complaint of employers when hiring economics graduates (for example in the Economics Network Employer Survey).

3.2 The first session

However familiar you are with your subject, the first session teaching it can be daunting, especially where the tutorial is interactive and students are unfamiliar with the tutor and potentially each other. Ultimately teaching is partly a performance, and we need to appear confident even if we do not always feel so. However, confidence needs to be balanced with approachability. Students should always feel that they can speak to tutors.

Students' expectations about the module and the tutor are largely formed in the first session. Moreover, student perceptions display inertia — it can be very difficult to change students’ views about the module later on. During the first class, the tutor can set the tone and familiarise students with the ‘rules of the game’. When this is done properly, the learning atmosphere is more likely to remain positive throughout the term. So the first session needs to be planned carefully. If you have a session during the first week, when little material has been covered, this can be a great opportunity to use the time to get to know each other and create a good learning atmosphere.

Things to include in the first small group teaching session (see also Section 4.7):

- It seems a basic point but do not forget to introduce yourself; not only your name, but also how and when you can be contacted.

Ask students to introduce themselves. Wherever possible it is immensely helpful to learn student names. Students appreciate it, but it may be particularly helpful if a student has problems. By knowing a student’s name you can more easily access further support services or resources for a student.

It will be useful to find out more than a student’s name. Student cohorts can be very diverse. There may be students in a class studying for different degrees, with different previous qualifications, very different motivations for taking a class etc. Hence, it can be invaluable asking students about, for example, the degree that they are enrolled on, their quantitative background etc. This can be done verbally, using Personal Response Systems (clickers) or software that allows students to answer questions using mobile devices. If technology is used, this can serve as an introduction to technology that will be used in subsequent tutorials. It can also be done by a short activity, which introduces students to the active learning tasks they will encounter in the module.

Teaching Tip

Consider asking students to interview their neighbour and then present their peer to the class. This way students already practice presenting and speaking up, something which you as an instructor will expect them to do on a regular basis.

- Students should all receive information on their modules, in the form of a module handbook. However, it may still be very valuable to spend a few minutes checking that students know where to get the learning resources they need for the module, understand the structure of the module, as well as how and when they will be assessed.

- Finally, set expectations of what is required of students and what will happen in sessions more generally. If it is not acceptable to come to class late, then indicate this. Similarly, tell students if you expect them to turn mobile devices off. Most importantly, tell students to what extent you expect them to participate in class. Prepare students for group work, for giving presentations, or for coming to the front of the class to discuss answers on a whiteboard.

Make clear to students if you do not plan on covering all material, for example all questions on a question sheet or everything from the book chapters, in every session. You should make sure that students know what they are expected to do on their own and whether you will focus on only the challenging content or questions. Crucially, make clear to students what work they are expected to do before coming to the session, as well as after.

Teaching Tip

Having noticed that students increasingly were forgetting to turn their mobile telephones off or turn the ring tone to silent, invariably leading to disturbances when a telephone rings, I established a rule: if anyone’s mobile (including mine) rings during class they have to bring sweets / chocolate / biscuits for the rest of the group to the next class. I have found that I do not even need to police the rule as students themselves are very keen to identify fellow students who should bring treats.

3.3 Planning a session

Every teaching session, assign some time for a proper introduction and a conclusion. Even though tutorials often seem too short, we must take time to introduce the subject, check that students are comfortable with the concepts to be discussed, and make sure they see how the lecture and tutorial complement each other.

"It looks as if there is not much communication between lecturer (module organiser) and class teacher. Often the class teacher is unaware of the progress made on the module or of what and how some material has been taught in the module."

As highlighted above, students complain if they see no link between lecture and tutorial content. However tempting, avoid ‘diving into’ solving problems or delivering core material, even if concerned about limited class time. Similarly, always end by summarising what has been covered, any follow-up work expected or that might be beneficial to students, and if possible, linking material covered with later material in the module.

Generally, take care to explain to students what is expected of them, not only during a teaching session, but also before and after in terms of work. Also try and provide an appreciation of how material is covered in the module. At university there is a much greater onus on the student to engage in independent learning. Students do not always appreciate what this entails, having been more closely guided prior to university, so this especially an issue for first year undergraduates. The first class may be a particularly crucial time to get students thinking about this.

Individual sessions are part of the larger learning journey students embark on. Be it a lecture, a class or an online activity, the question arises how individual teaching sessions fit together.

Teaching Tip

Do not view small group teaching sessions as stand-alone events. Rather, consider — and communicate to students — how they fit with previous and future sessions in the module.

When thinking about sequence, first think about the aims of the individual teaching session within the larger context of the module (i.e. does the session introduce new material, does it take up ideas from the last lecture(s), etc.) and then consider what students should do before and afterwards. A guiding question when planning teaching should always be what students do before, during and after the session.

Table 2 summarises some ideas about student activities before and after the session.

| Student Activities | |

|---|---|

| Before session | After session |

| Check understanding of lecture material | Extend beyond core reading |

| Make notes on further reading | Check notes are complete on a topic |

| Attempt relevant online quizzes | Check question sheet answers are complete |

| Prepare answers to set questions | Collect relevant past examination questions |

| Consider applications / examples | Attempt past examination questions |

| Formulate questions for the tutor | Check understanding of how a topic ‘fits’ into a module |

3.4 Teaching question-based problem sets

Most commonly economics tutorials provide students with the opportunity to develop the knowledge gained in lectures. Each tutorial relates to particular lectures and students are required to prepare answers to a set of problem set questions either in advance or during the session. Such problem sets are common for technical material, including model work and derivations. However, they can also be used for interpretive material, where essay-type short answer questions are set on — for example — an assigned reading.

It can be tempting for a tutor to simply go through the answers to the problem set questions on the whiteboard at the front of the class. Students often seem to favour this, as the onus is on the tutor to provide solutions. There are several problems with this approach. Learning happens best when students construct knowledge. As discussed in section 2, retention rates and understanding remain low when students copy results without attempting the questions themselves. Furthermore, this is a very expensive mode for just ‘giving out sample solutions’. In fact, printing solutions and running an office hour in case a student has questions may be an easier way of achieving the same goal. In addition, if the tutor presents the answers to all the questions set during the teaching session, students have less incentive to prepare the work prior to coming to class, or even to attend class.

Interactive and engaging teaching sessions, by contrast, encourage students to prepare for sessions in advance, will help students identify material that they find difficult, will facilitate ‘deeper learning’ and thus improve recall at a later date.

When planning a problem-set based teaching session, work through the question sheet and consider which questions to cover. Do not feel under pressure to go through every question but if you decide not to discuss particular questions make sure you explain to the students why you chose not to cover certain questions. Potentially coordinate with other tutorial teachers and discuss the fact that you will not cover all aspects with the module leader. However, also be prepared to be flexible. Ask students which questions they found most challenging, either during class with a show of hands or online voting or in advance of sessions; this information will help you prepare.

Plan approximately how much time to spend on different activities in the session. For example, you may want to allot time for students to check answers with each other; to prepare answers to present to the rest of the group; to play a short, illustrative economics game etc. Consider whether sessions can be planned so that there is a mix of individual, small group, and whole class activities, so as to keep students engaged.

“Spoon feeding in the long run teaches us nothing but the shape of the spoon.”

E. M. Forster

Evidence (for example Springer et al. (1999)) points to benefits for students working in small groups, The question therefore arises of how we can get students to work effectively in such settings. In the following boxes we share some ideas on possible approaches. Remember, for any interactive teaching session, it is vital to plan carefully in advance.

Group work

Ask students to work in small groups — each group may work on a different question — with each group expected to present their answer to the rest of the class. To save time, the student groups can be asked to prepare their presentation prior to the session. If presentations on different questions are prepared in advance they can be uploaded to the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) to create a bank of student answers. However, the answers should be checked by the tutor for accuracy before being uploaded.

Once students gain confidence from presenting their work in groups, it is easier to ask them to contribute individual answers.

Student Discussions

Especially effective for interpretive sessions, this is good for getting students to reflect on different sides of an argument. Students could be split into two groups (there are several ways of forming groups and you may wish to mix them up) and each group asked to reflect on arguments for a specific position. Make sure students use economic evidence to support their arguments. It is vital to ensure the level of the discussion is appropriate to the academic setting.

Let students prepare a 5 minute speech to formulate some of their arguments and then start the discussion. During the discussion, your role is one of moderator. You may allocate speaking time, ask groups directly how they would counter a specific argument, ask clarifying questions etc. You may also stop the discussion for a short time to review some economic arguments.

Teaching Tip

For example, a discussion about the appropriate amount of abatement to combat climate change may be put on hold when students talk about discounting. You as an instructor may review the concept of discounting before getting back into the discussion. It is your role to clearly define the learning outcomes (the concepts and arguments the students should grasp) and moderate the session to achieve these.

Role Play

Role Play could be a variation of the student discussion. In particular, you could assign specific roles to students.

Teaching Tip

In a discussion about environmental damage after a large oil spill I once let students discuss ways of estimating compensation payments to local fisheries. I assigned the role of the oil company, an economist, an environmentalist, and the local fishery to different groups and ‘played’ a discussion about the appropriate compensation payments. The exercise enables students to reflect about different approaches to calculate economic value and that the choice of method and aspects to include may strongly depend on personal preferences.

Student Presentations

You may ask your students to prepare presentations on a specific topic or a research paper, where you use the questions in the problem set to guide the flow of the presentation.

There are several advantages to letting students present problem set answers. First, the problem set questions can be micro-tuned to assure a specific flow of the presentation. Second, by explaining to others, students can show whether they have really grasped the concepts and workings of a model. Third, the students gain transferable skills important for the workplace. In principle, student presentations can be used for both interpretive and more quantitative material.

Students can either present answers by themselves or in small groups. In the first case, students may be asked to prepare material, for example read a research paper. A first question could be to summarise the article in a few sentences. One could then pick out specific concepts and questions and let students reflect on these. For more technical material, one could ask students to prepare a short presentation of a specific technique, explain the steps of a derivation or use a graphical model to run through a specific economic argument.

As an instructor, you want to make sure the whole group is engaged, rather than one individual. This can be easily achieved by stopping the presentation and asking the group questions like: “Why did the student do a specific step?”, “What is the potential problem with this approach?” or “How else could we have answered the question?”. The structure of a problem set may also lend itself to mixing up presenters.

Teaching Tip

Instructors often claim it is difficult to get students to the board. One way of achieving this is to ask students first for an answer. If the answer is correct, congratulate the student and ask if she/he could write it up on the board. Once in front of the class, the student can be asked another question.

3.5 Revision classes

Revision classes need to be prepared carefully. It is tempting, especially as teaching draws to a close, to think that all that is required is to turn up and answer student queries without divulging too much information about the forthcoming assessment. However, revision classes require careful planning and preparation to ensure that students gain as much benefit as possible.

First, consider if there is any information (other than the topics of unseen assessments that students invariably ask for!) that can usefully be provided to students. Examples include:

- A brief overview of the overarching structure of the material covered in the module

- Guidelines as to the format of a forthcoming assessment and any information that will be provided, for example an equation sheet, copies of statistical tables etc.

- Past assessment questions

- Specimen past answers

- General assessment feedback documents that were circulated to students who sat the assessment or examination previously

- Module or assessment specific marking criteria

- Details of the marking process

- Resit provision

We often assume that students are informed about the format of assessments and marking criteria, but we should not lose sight of the vast quantity of information that students receive. When providing information, such as the items suggested in the list above, also set aside time to talk through the documents, and give students an opportunity to ask questions. For example, marking criteria statements may be easy to understand for an academic or teaching assistant, but challenging for students.

Students may not be aware of the rigorous marking procedures in place in universities. It can be reassuring to students to know their work is marked by one (internal) marker, with at least a sample marked by a second (internal) marker, with a sample also being looked at by an external examiner. Further, that attention is given to the distribution of marks across a cohort and any papers that receive marks close to classification borderlines are given particular attention at multiple stages of the marking process.

Check whether any past scripts have been saved and whether former students gave permission for anonymised answers to be circulated. Students often find it enlightening to see examples of good and weak answers by former students. Examples of high quality work can inspire students to do well, while both stronger and weaker past work, alongside marking guidelines, can help students appreciate what is expected of them.

Teaching Tip

Consider using an online forum to collect questions. In such a forum students can also answer questions of their peers. This will facilitate student discussion and enable students to explain material to others, which is the ultimate check of whether the material has been truly understood.

Consider whether you would like students to undertake any specific activities in advance. To help both tutors and students prepare, students can be invited to submit questions in advance for consideration. Similarly, students can be asked to prepare draft answers to previous years’ questions.

Ideally a revision class should remind students of the overall narrative of a module and provide students with an opportunity to clear up any niggling doubts about material covered, while providing an opportunity for them to appreciate what is required for a first class / distinction level answer. Revision classes should be interactive with lots of opportunity for students to ask questions and contribute.

Teaching Tip

A competitive element can also be introduced. Asking questions using personal response systems or mobile devices can help students discover where they may have gaps in their knowledge. Similarly, a team game based on ‘Noughts and Crosses’ can be used to encourage students to answer questions and also set questions for another team, in so doing offering an additional opportunity for students to revisit their module notes. This game is outlined on The Economics Network website.

Consider whether to recommend specific activities for after the class. Students know they need to learn material but may less clear about how to learn. A student may take in little from reading a text book for even an hour, and may need suggestions as to how to vary their revision activities. Consider recommending any of the following:

- Diagram drawing practice

- Self-testing on frequently used mathematical or statistical methods

- Past question practice, maybe writing essay plans rather than full essay answers

- Reading relevant recent newspaper articles for illustrative examples to support answers

- Revising with other students

- Discovering academic references beyond those recommended on module reading lists.

Teaching Tip: Reviewing previously submitted work

One activity that students find hugely beneficial is reviewing work previously submitted by students. This could be work submitted for module assessments or answers to past examination questions. You must remember to get students’ permission to use their work and ensure it is anonymised. Give examples of very good and also weak answers. Students can be asked to read answers in advance or in class, and then asked as a group to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of the answers, offering suggestions as to the appropriate marks. Consider doing this in conjunction with the marking criteria. The resulting discussion is often very lively and revealing to students, highlighting what is expected of them.

“I found the evaluation of previous projects extremely helpful in understanding what was wanted from me — it would be great if other courses took this up!”

4. The skills of the class teacher

As a class teacher you will need to hone your personal and communication skills. In particular, your listening skills, questioning skills, ability to give complex and difficult explanations and your ability to end classes effectively. This section includes some advice in these areas.

- 4.1 Effective listening

- 4.2 Questioning skills

- 4.3 Clarity of explanation

- 4.4 Teaching diverse classes

- 4.5 Bringing classes to a close

- 4.6 If your first language is not English

- 4.7 Top Tips

4.1 Effective listening

- Try to keep an open mind and listen to what is actually said.

- Listen for meaning. For example a student maybe asks you a muddled question about a small detail. Actually, what s/he may be telling you is that s/he is completely lost and doesn't understand this at all - or this student may be dyslexic.

- Try not to pre-empt what a student is saying, by cutting them off mid-question and giving them an answer to a problem as you see it. As much as possible, let them explain their uncertainties and confusions. According to a reasonable body of the Higher Education research literature, concept development often requires that students first understand how new ideas presented fit in relation to what they already know, and IF the new concept requires them to let go of some previous understanding, this needs to be actively acknowledged (ie: you can't simply overlay a new and contradictory set of ideas before the old ones have been explored and deconstructed).

- Try to find a workable balance between, on the one hand, thinking ahead in the discussion in order to maintain the flow and focus and, on the other, being overly directive and forcing the discussion along your set path.

4.2 Questioning skills

There are a number of techniques you can use to encourage students to ask questions and to open up discussion.

The most obvious is to draw on students' questions and comments and to enlarge upon them with your own remarks. What do you do if the subject matter is new and your students are too?

You may want to jot down several statements or questions beforehand and use these as a springboard.

For many quantitative subjects, you may want to plan out a sequence of short questions aimed at helping students work their way through a problem, or grasp a better understanding of a theory or model. A number of class teachers in Economics, Maths, Statistics and Accounting and Finance use this approach. Some will go round the class more or less sequentially, so students know when their "time" to answer is approaching and can prepare. Others take a more random approach, calling on people by name. Yet others ask questions to the group as a whole, and let whoever wishes to respond.

This issue, of whether or not to call on students individually and by name to contribute to the class, is one of the more controversial aspects of questioning. Clearly tutors have different styles and students will have varied expectations. The advantage of addressing individual students is that you can tailor comments and make interventions that are appropriate for specific students. It may be a way of involving a very quiet student who you know has useful contributions to make but finds it difficult to raise them in the class. However, great care should be used when 'spotlighting' students. If some students think that they may be 'picked on' to answer questions it may make them very uncomfortable in the class and less able to think and work out their own position or solution. (This may particularly affect the non-native speakers of English in your class and those with disabilities.) This may also have a knock-on effect on the other students and so the positive atmosphere in the class can be eroded.

If you choose to use a direct questioning approach it is also sensible to think through what you will do when a student cannot answer your question or gives a muddled or an incorrect response. It is likely to fall to the tutor to 'rescue' the situation and in some circumstances to help re-build the confidence of an embarrassed or flustered student. Because of these potential difficulties it is, therefore, suggested that you do not ask individual students to answer your questions so directly until you have established a good rapport with your class and you have got to know your students better.

With more discursive subjects, it is generally preferable to open up discussion with open-ended questions which will get students thinking about relationships, applications, consequences, and contingencies, rather than merely the basic facts. Open questions often begin with words like "how" and "why" rather than "who", "where" and "when", which are more likely to elicit short factual answers and stifle the flow of the discussion. This more closed questioning approach tends to set up a "teacher/student" "question/answer" routine that does not lead into more fruitful discussion of underlying issues. You will want to ask your students the sorts of questions that will draw them out and actively involve them, and you will also want to encourage your students to ask questions of one another. Again, it is for you to decide whether to call on students directly, or leave the discussion and discussant "open". Above all, you must convey to your students that their ideas are welcomed as well as valued.

Very occasionally you may have a student in your class who suffers from more than the normal level of anxiety or shyness when called upon to contribute to the class discussions or to present their work. In some circumstances this may be related to a disability, or to language proficiency. Treat such situations with sensitivity and if appropriate seek specialist guidance.

Top Tip

"On the introductory workshop we heard about a discussion technique that works well for me. I ask a question, I then ask the students to write down their answer and then compare it with the person sitting next to them. I then ask the question out loud to the group again and I always get someone happy to kick off the discussion."

There are a number of pitfalls in asking questions in class. Here are the four most common ones:

- Phrasing a question so that your implicit message is, "I know something you don't know and you'll look stupid if you don't guess what's in my head!";

- Constantly rephrasing student answers to "fit" your answer without actually considering the answer that they have given;

- Phrasing a question at a level of abstraction inappropriate for the level of the class - questions are often best when phrased as problems that are meaningful to the students;

- Not waiting long enough to give students a chance to think.

The issue of comfortable "thinking time" is an often-ignored component of questioning techniques. If you are too eager to impart your views, students will get the message that you're not really interested in their opinions. Most teachers tend not to wait long enough between questions or before answering their own questions because a silent classroom induces too much anxiety for the class teacher. It can be stressful if you pick on a student for an answer and all the group are waiting for a reply (see below). Many students, particularly those with certain disabilities or dyslexia, students who are not confident in speaking in public, or not confident in speaking English, may become unduly flustered in such a situation. Creating a more comfortable space in which to think is likely to induce a better 'quality' of answer and increase the opportunities for all students to contribute effectively.

The above approach is likely to help make your students feel more confident for a number of reasons. First the students have the chance to 'check out' their answers with a peer; secondly, they are required to 'rehearse' and put their thoughts into words; and thirdly the answer gains a form of endorsement from the peer which increases confidence in its value. Once the students have confidence that you will give them time to think their responses through, and you show them that you really do want to hear their views, they will participate more freely in future.

Asking Questions Relating to Work Students Have Not Done

This is clearly a different issue from those noted above, and comes back to issues around agreeing ground rules with students to ensure that they prepare adequately for class. It is important to establish agreed working patterns from the start, and follow them through.

4.3 Clarity of explanation

The first piece of advice here is to try not to do too much explaining in class. This may sound a little strange but it is all too easy to be drawn into the trap of giving mini-lectures rather than facilitating learning. However, there are times when your students will look to you to help in clarifying points or linking class discussions and course work with related lectures.

In giving a clear explanation you should start from where your learners are. You may choose to summarise "what we know already" or indeed ask one of the students to do this task for the group. There are four quick tips to help structure your explanation:

- Structure what you say so that you have a clear beginning, middle and ending;

- Signpost your explanation to make the structure clear to everybody;

- Stress key points; and

- Make links to the learners' interests and current understanding. You can do the latter through the use of thoughtful examples, by drawing comparisons and by using analogy.

Top Tips

"All too often students come to class unprepared, sometimes without even having read the question. Thus, reading the question before getting into the answer can be very important. One of the greatest skills is to succeed in making relatively unprepared students understand, and take an interest in the questions at hand, without compromising the level of the explanation offered or delaying the progress of the class." One class teacher goes round the class each week to check who has attempted that week's problem set. Students only need to hand in two pieces of work per term for tutor marking. However he finds that by doing the round weekly, most students do the exercises in advance most weeks, and will be candid (and generally give convincing explanations) when for some reason they have not been able to do the work.

"I try to think of really good examples to illustrate the main points I want to make. If you can find something current from the papers or the news then you are often onto a winner - I like to bring along the paper and hand it round the group. I thought about asking the group to bring in their own examples too and I might try this next year."

4.4 Teaching diverse classes

- Give "minority" students equal attention in class, and equal access to advising outside class. Don't overlook capable but less experienced students.

- Give "minority" students equal amounts of helpful and honest criticism. Don't prejudge students' capabilities.

- Revise curricula if necessary to include different kinds of racial and cultural experiences, and to include them in more than just stereotypical ways.

- Ensure that the teaching methods and materials you use are accessible to students with different learning abilities and disabilities

- Monitor classroom dynamics to ensure that "minority" students do not become isolated.

- Vary the structure during the course to appeal to different learning styles and modes of learning.

- Don't call on "minority" students as "spokespersons" for their group, e.g.: "So how do Moslems feel about...?".

- Recognise and acknowledge the history and emotions your students may bring to class.

- Respond to non-academic experiences, such as racial incidents, that may affect classroom atmosphere and performance.

Adapted from "General principles in teaching 'minority students'", in A Handbook for Teaching Assistants, University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB)

4.5 Bringing classes to a close

Getting the timing of classes right can be a challenge to most teachers. There is inevitably pressure on time, as many classes try to "do" as much as possible in the time available. Finding that time has simply run out is a common experience. With that in mind, it is useful to plan the end of sessions as carefully as planning the beginning, and then to watch the clock so that you can decide when the "end game" needs to start. An obvious element in "ending" that many class teachers include is to summarise the ground that has been covered, key learning points and main issues raised. This can give a sense of "neatness" and closure to sessions.

Another way of looking at the end of a class though is to see it as an opportunity to prompt students to further study. Rarely will a class manage to "complete" the topic under discussion. As such, you may wish to consider ways of using the summing up more as an opportunity to identify any "gaps" or issues that haven't been addressed, key readings which you may be have noted students have not yet read, but probably would benefit from spending time on, and in giving students some pointers as to further work they may engage with. Finally, it is often worth reminding students what will be covered in the next class and prompting them to plan ahead, to make links to the next lecture and class, and ensure that everyone is on track to make the most of the next class in the series.

Top Tip

"I find important ending the class with a summary of the key arguments discussed, results found and conclusions drawn."

"wishing them a nice weekend at the end of class, showing that they are cared for"

4.6 If your first language is not English

Many class teachers in UK universities are post-graduate students who are themselves from overseas. Teaching in a foreign language can be a fantastic way of improving your English.

However it may also present a number of challenges too. Here are a few common sense reminders if this applies to you.

- Always face your students when you are talking to them so that they can also use your eye contact and body language to fully understand your meaning.

- In discussion, write down key terms and names when you are referring to them. You can do this on the white board or flipchart as you speak or include them in a brief handout and explicitly refer to them in class.

- Encourage your students to ask questions.

- Try to talk slowly and clearly so that students will have every opportunity to understand what you are saying.

- If your students ask you a question that you don't understand, you can:

- Ask the student to repeat or rephrase the question;

- Open up the question for the whole class to think about (e.g. "That's a good question can someone begin to help us answer it?");

- Attempt to rephrase the question yourself and answer it when you are sure you understand correctly.

If you experience problems with being understood, your institution may be able to provide voice or pronunciation training: check with your staff development department.

Top Tip

"I know my English isn't perfect, so when I met my class I said to them 'you need to stop me if I talk too fast or my accent is too strong'. We needed to sort out how they could stop me without feeling embarrassed - one of my groups actually wave at me if I lose them!"

4.7 Top Tips

| Start off on the right foot | by getting to know your students’ names; encouraging them to learn each other’s names; contracting; establishing ground rules; setting objectives and orientating them to the module. |

|---|---|

| Use ‘structures’ to manage group learning | by arranging the furniture in the room suitably; breaking up the group, breaking up the tasks; using sub-groups (pairs, triads, pyramids, debate etc). |

| Encourage students to participate | by using structures (e.g. rounds, brainstorming); using students’ interests; using students’ questions; asking different kinds of questions; managing the vociferous students effectively. |

| Encourage students to take responsibility | by distributing group roles; encouraging students to work alone or in groups in class; leaving the room; asking students to present their work; establishing and supporting self-help groups; awarding group grades. |

| Evaluate the work of the group | by encouraging group self-monitoring; having group observers; checking up on group process; tape-recording the session; consulting the group. |

| Use written material | such as posters; group charts; students’ notes; handouts; essay preparation; open-book tutorials. |

| Help students express their feelings | by dealing with ‘what’s on top’; self-disclosure; praise and encouragement; managing closure. |

5. Preventing and resolving problems

- 5.1 Common difficulties in facilitating class discussions

- 5.2 Suggested DOs and DON'Ts for running problem-solving classes

- 5.3 Dealing with difficult students

- 5.4 Getting feedback

5.1 Common difficulties in facilitating class discussions

The following are some of the common problems that can occur in classes and some ideas about how to cope with them:

- The whole group is silent and unresponsive — ask students to work in pairs to get people talking and energised. Ask "What is going on?" Ask groups of four to discuss what could be done to make the group more lively and involving and then pool suggestions.

- Individuals are silent and unresponsive — use open, exploratory questions. Invite individuals in: "I'd like to hear what Clive thinks about this," Use "buzz" groups (pairs or groups of three).

- Sub-groups start forming with private conversations — break them up with sub-group tasks. "What is going on?" Self-disclosure: "I find it hard to lead a group where..."

- The group becomes too deferential towards the tutor — stay silent, throw questions back, open questions to the whole group. Negotiate decisions about what to do instead of making decisions unilaterally.

- Discussion goes off the point and becomes irrelevant — set clear themes or an agenda. Keep a visual summary of the topics discussed for everyone to see. Say: "I'm wondering how this relates to today's topic." Seek agreement on what should and should not be discussed.

- A distraction occurs (such as two students arriving late) — establish group ground rules about behaviour such as late arrivals. Give attention to the distraction.

- Students have not done the preparation — clarify preparation requirements, making them realistic. Share what preparation has been undertaken at the start of each session. Consider a contract with them in which you run the seminar if they do the preparation but not otherwise.

- Members do not listen to each other — point out what is happening. Establish ground rules about behaviour.

- Students do not answer when you ask a question — use open questions, leave plenty of time. Use buzz groups. Ask students to write down their answers first and share with a neighbour.

- Two students are very dominant — use hand signals, gestures and body language. Support and bring in others. Give the dominant students roles to keep them busy (such as note-taker). Use structures that take away the audience. Think about how you position yourself. If you sit next to them rather than opposite them, it is harder for them to "come in". See if you are giving them too much "non-verbal" encouragement, such as nods, eye contact and positive comments. You may need to break some social rules now and then!

- Students complain about the seminar and the way you are handling it — ask for constructive suggestions. Ask students who are being negative to turn their comments into positive suggestions. Ask for written suggestions at the end of the session. Agree to meet a small group afterwards.

- Students reject the seminar discussion process and demand answers — explain the function of seminars. Explain the demands of the assessment system. Discuss their anxieties.

- The group picks on one student in an aggressive way — establish ground rules. Ask 'What is going on?' Break up the group using structures.

- Discussion focuses on one corner of the group and the rest stop joining in — use structures. Point out to the group what is happening. Look at the room layout, how are students positioned and where do you sit? — see if physical re-organisation can make a difference to undesirable group dynamics or can enhance discussion flow.

Adapted from materials produced by Dr Alan Booth (University of Nottingham) and Jean Booth (University of Coventry). Enhancing Teaching Effectiveness in the Humanities and Social Sciences: participant guide (1997) UK Universities and Colleges Staff Development Agency, Sheffield, p115-6.

5.2 Suggested DOs and DON'Ts for running problem-solving classes

With thanks to Tony Whelan from the LSE for some of the following. Tony is a highly experienced class teacher who has run classes in Maths, Statistics and OR.

Possible DOs for running problem classes

Provide background: In some sessions, it may be appropriate to discuss the theory and methods involved in a topic, at a fairly general level, and then to use that discussion as the basis for approaching the issues raised by homework exercises.

On an elementary statistics course, homework revealed that students had considerable difficulty with one important idea, namely that of an estimator. One successful class session involved spending half the time studying the relevant definitions and properties, with lots of examples of things that were, and that were not, estimators. This clarified the issues involved, and it was then possible to go back to the homework questions and clarify how the basic ideas applied in all of them.

- Read and contextualise the question(s): In most sessions it is fruitful to encourage students to read questions carefully and to absorb the information in the question. In many applied areas this can be motivated by the observation that, in the "real world", real problems require considerable effort and thought to decide what is important about them, and what mathematical approach(es) might be fruitful.

Identify thought processes: In most sessions it is also fruitful to discuss the thought processes that students need to engage in while approaching how to solve a problem: at each stage, students need to be able to decide, "what should I do next"?

In an elementary statistics course, there are strategies for calculating probabilities using two results known as Bayes' Formula and the Total Probability Formula. It is often useful, at an appropriate stage, to (re-)display those results, in a different colour from the "solution", to remind students just why the next calculation is the appropriate one to carry out. Similarly, in explaining the Gaussian Elimination method of manipulating matrices, it can be useful to put coloured boxes around the key cells and blocks being used at various stages in the calculations.

Use examples: It is frequently useful to motivate ideas and techniques by reference to real-world examples.

In an elementary statistics course, students meet the concept of "outliers", that is to say values in a set of data that seem a long way away from the bulk of the known data. In real-world situations, such anomalies can be due to, for instance, instrument errors. The discovery of the famous hole in the ozone layer, over Antarctica, illustrates both the importance and the difficulty of dealing with this problem in "real-world" situations: it was discovered using meteorological balloons, but then the question arose why meteorological satellites observing the same area earlier had not identified it first. It turned out that the computer programmes used to analyse the satellite data had been so written as to reject, as "outlier" instrument errors, true readings which ought to have revealed the ozone hole but were ignored until it was discovered a different way.

- Prepare and structure: Make sure that classes are well prepared, with a proper structure: some ideas about this can be found just above.

- Explain, then summarise: Be prepared to repeat things, often from slightly different angles, and to summarise the ideas you are trying to get across, e.g. as bullet points.

- Observe your audience: Pay careful attention to whether students appear to be following what is being said: there are all sorts of clues that can help with this, involving body language and facial expressions as well as any explicit questions or interjections that they make.

- Encourage participation: Even when a class teacher is dominating the discussion (which will often be the case in problem-solving classes), s/he should make sure that students are encouraged to yell out if something is unclear, or wrong.

- Involve students: One other technique that helps to involve students, even when a class teacher is dominating the discussion, is from time to time to ask something like "Someone tell me what comes next". This approach can be varied by asking particular students something similar, but whatever detailed approach may be used, teachers need to be aware of the twin dangers of the "pushy" student, who likes to show off how much s/he knows, intimidating or discouraging others, and of the shy or nervous student, who needs to be encouraged to respond in such situations.

- Use follow-on exercises to check on understanding: Students can be told in advance that they will be given an exercise in class as a follow-on from, or as another example of, an exercise they have prepared. They could work on these in small groups with the groups reporting back.

- Give students enough time: If you give students work to do in the class as a follow-on exercise from the ones they have prepared, give them enough time to complete it, or at least to get sufficiently far through it to benefit from the subsequent explanation.

Definite DON'Ts in running classes

- Read aloud: Don't just read out, or ask students to read, pre-printed solutions supplied by the teacher in charge.

- Skip parts of explanations: Don't "skip" detailed points of reasoning on the grounds that they are "easy" or "obvious". Maintain a consistent level of depth of explanation and remember that points that are "obvious" to you may not be so to your students.

- Rush: Don't go too fast.

- Try to hide errors: Don't be afraid to acknowledge errors when they happen or to admit that there is something you do not know. If asked a question that you feel you cannot accurately/adequately address on the spot, then do not waffle or offer a vague explanation. Tell the students you will look into their question and let them know. Make a note of any unresolved questions or queries and make sure you get back to them with a response.

5.3 Dealing with difficult students

At some point in your career as a class teacher you may have to deal with a student who causes disruption in the class or who does not meet his/her course-related obligations, such as handing in assignments, attending classes regularly, etc. Although each case will be different, you will need to take some steps. Here are a few tips:

- If a student who is on the class register does not attend the first class/classes, check that your class register is up to date and, if so, contact the student to remind them they should be attending class, informing them of your office hours in case they wish to come and discuss the course/classes they have missed with you. Typically, students will respond to this and start attending more regularly. If such encouragement is ineffective, then alert the student's tutor/other appropriate member of staff about the matter, copying in the student.

- If a student does not submit the required assignments, then contact the student and give them a reminder and, if appropriate, a final deadline for submitting work. Be flexible and understanding if a student is facing some particular personal or academic difficulty, but maintain a level playing field for the whole group. If failure to submit coursework persists, alert the student's tutor and copy the student.

- Familiarise yourselves with the regulations relating to course assessment so as to advise students accordingly.

- If a student causes disruption in class, for example is rude, aggressive to other students, uncooperative etc, then you have to decide whether the level of class disruption is such as to necessitate intervention (asking the student to stop or, in extreme cases, to leave the room), or it is sufficient to speak to the student later, outside class, about the matter. If you ask the student to leave the classroom, then contact the student's tutor and the undergraduate/graduate tutor directly after the class and explain what occurred. Take care not to offend or humiliate any student in front of his peers, even if his/her behaviour is very challenging.

- Different class groups taught by the same GTA may have different atmospheres. Some may be boisterous and loud, while others may be quieter. It is inevitable that the mix of student personalities and that of the class teacher will jointly determine the atmosphere in the classroom. Sometimes a simple solution is to move a student to a different class group, if possible.

- Keep organised e-mail records for students that cause problems so as to be able to provide an accurate account of the problems at a future date if the need arises.

- Students may try to undermine your authority as class teacher if they perceive you as not being very assertive. Different approaches work for different people but deal with problems professionally as soon as they arise in order to prevent escalation.

- Take time to understand what is motivating the poor attendance/challenging behaviour of students and take steps to encourage and motivate them.

- Ask for advice if faced with problems that you are unsure how to tackle.

5.4 Getting feedback

At various points in the year, you will want to assess how well you and your students are doing. Here are some suggestions to help you evaluate your classroom teaching:

Checking student progress

- As noted in 'questioning skills' in the section on 'the skills of the class teacher', ask questions designed to monitor student understanding. This is an informal way to assess student progress.

- Watch for student reactions to your discussion section. Take notice of body language and eye contact.

- Consider using short quizzes designed to monitor students' understanding of the previous week's material. (The Economics Network has links to many tests and past papers that you might want to use or adapt.)

- Try out an "instant questionnaire". This is a simple technique of asking three or four "indicative" questions or statements about a particular session, and getting an instant response to them from the students. Statements might take the form of "I now feel confident to tackle problems about x", "Today's class was too fast for me", "I really feel I need more help on understanding theory y", etc.

Feedback on your class teaching approach

- Ask students how things are going, over coffee, or when they come to see you in office hours.

- A few weeks into term, ask students to jot down answers to the following: what would you like me to stop doing; continue doing; start doing? (Think of variations on this theme, for example asking them to comment similarly on what they'd like from their fellow students in the class.)

- Using peer observation of teaching sessions can also greatly benefit the reflective class teacher. It can be very useful to agree to observe and be observed by another class teacher reciprocally to help develop teaching skills.

- Invite the teacher responsible for the course to observe your teaching and arrange a feedback session afterwards.

- You may wish to videotape your classes to review your own approach (you would need to consult with your students about this and probably explain that it is for your benefit and therefore ultimately for their benefit!).

Top Tip

"I asked if I could sit in on one of the experienced class teacher's classes, before I met my own group, just to see how he did it. I really liked his approach but I knew I wouldn't have the confidence to mimic him - still it gave me an idea of how to break up the time and how to avoid doing all the talking."

6. Conclusion

A teaching assistant working with a small group of students has the opportunity to create an environment where students can follow a more individual learning journey and actively engage in the learning process. The chapter has offered various ways to achieve that active engagement. This mode of teaching is demanding, as interaction also means unpredictability, but can be extremely fulfilling.

Hopefully these suggestions are the basis for you to develop your own style of teaching. This handbook's chapter on using media in teaching goes further into using social media, online video or personal response systems. Other chapters go into other specific topics in teaching economics and the Ideas Bank has many case studies of specific activities. Consider what is feasible in your own classes and what fits the way you want to teach.

References

Biggs, J. (2007): Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 3rd ed. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Bruner, J. (1960): The Process of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1966): Toward a Theory of Instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Piaget, J. (1950): The Psychology of Intelligence. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Sousa, D. A. (2006). How the brain learns (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Springer, L., Donovan, S. and Stanne, M. (1999) ‘Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: a meta-analysis’, Review of Educational Research, 69(1), 21-51. DOI: 10.3102/00346543069001021

Tyler, R. W. (1949): Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.